Rope (1948) is a classic murder mystery directed by Alfred Hitchcock, based on the true story of two college students who killed their neighbor.

The film is a stroke of genius in many ways, including its long takes (some of them 20 minutes long), its interesting camera positioning, and its chilling irony that pervades every seen.

But for today, I’m going to focus on just one interesting thing. It has to do with a fundamental human ability, something that sets us apart from most other animals.

As explained by Max Bennett in The Evolution of Intelligence (and summarized in the video below), what separates mammals from animals like reptiles is a brain structure called the neocortex, which gives them the unique ability to imagine the future, before it occurs. However, they are only able to simulate these futures based on their own experience, i.e. something that they themselves have previously done.

But primates, and great apes in particular (which we belong to as Homo Sapiens), have another structure called the prefrontal cortex, which gives us the even more powerful ability of empathy. This means we are able to imagine possible futures based on the experiences of others—even if we have no direct experience ourselves. The classic example is watching your friend trip on an obstacle, and then avoiding that obstacle yourself.

This may seem trivial, but it is actually an incredible leap forward in the evolution of intelligence; something so rare that only a few species have it.

Empathy also allows us to intuit when other people like or don’t like us, based on the most subtle cues. It allows us to imagine what they might be thinking about us, or another person.

This is crucial in social situations, when a conflict might be brewing, allowing us the opportunity to de-escalate, or simply run away. It’s also invaluable for engaging in romance, helping us discern when someone is into us or thinks we are repulsive.

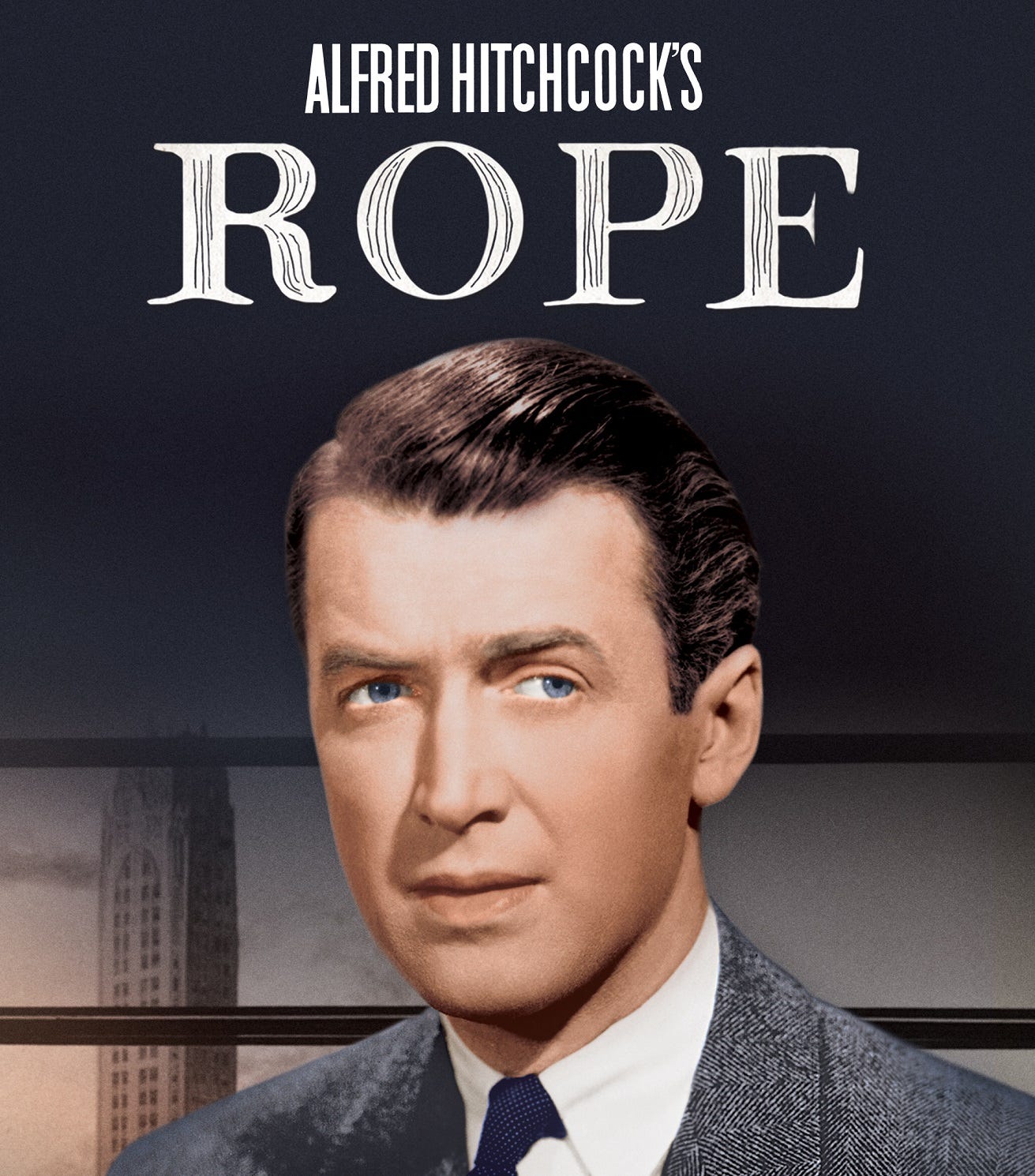

To tie this back to Rope, the character Rupert (played by James Stewart) is able to imagine what is going on in minds of the killers, realizing the awful truth, while everyone else in the story is oblivious.

What I find interesting about this is the contrast between Rupert and the other lead, Brandon (played by John Dall).

Brandon is one of the most charismatic characters I have ever seen on the big screen. He is affable, witty, good-looking, suave, and intelligent. His voice is honeyed and melodic. Several times people insult him, mock him, or downright accuse him, and each time he lets it slide over him like water off a duck’s back. Even when Rupert is on to him, Brandon doesn’t lose his cool. He manipulates all the other people into doing what he wants, like a puppet master.

Contrast that with Rupert, who is awkward, cerebral, and stiff. He speaks in short, choppy cadences with odd vocal inflections. He doesn’t know how to react to people who baffle him. He clearly doesn’t get out very often.

In short, Brandon appears to be a master of human nature, gracefully orchestrating a grand party, while Rupert is a robotic dweeb, who can’t even figure out how to hold a conversation at said party.

However…

Brandon is also a cold-blooded killer (more reptilian than mammal). He kills his close friend, not out of passion or jealousy or anger, but merely because he is curious about what it feels like. He also hosts a party over the corpse, inviting the dead man’s parents and fiancé.

Meanwhile, despite his awkwardness and seeming inability to relate to others, Rupert is the only one at the party who actually notices something is up. He is the only one sensitive to the peculiar actions and words of Brandon and Phillip. Of all the characters in the film, he shows the most awareness and intuition of human nature.

The point: Charisma is not the same thing as Empathy.

In fact, we usually notice that the two are indirectly related. Those who are the coolest and most popular kids in high school are usually the biggest assholes. Celebrities and those with success and power tend to demonstrate the same disregard for everyone they consider “lower” than themselves.

This is easy for me to say because I am not a celebrity, and in high school I was a huge nerd… and I probably still am. As painful as that experience was, it gave me something invaluable— empathy for the outcast.

I now feel pretty comfortable at parties or social gatherings, but I have a sixth sense for people who feel awkward and uncertain. Why? Because I know exactly what it feels like to be that person, and I can notice the signs and symptoms immediately. And so I make it a point to go talk to those people.

I’m not trying to say I’m a really nice guy. I’m saying I have spent much of my life feeling like a loser, so I can relate.

I also know what it feels like to be disabled. I’ve spent nearly a year of my life on crutches (across two injuries). I know how annoying it is to have people look at your disability and ask you, “so what happened to you?” And so I don’t ask injured people about their injuries. I just treat them like normal people because that’s how I always wanted to be treated when I was in their shoes (or cast).

I know what it feels like to be someone’s servant. I’ve worked in service jobs as a cook, a mechanic, and now an EMT. On a recent Saturday, my friend said, “well most people are off work today.” And I know that’s not true—most people work blue collar jobs, like I do, and we work any day regardless of whether it’s a weekend. We work at all hours of the day and night, on holidays, on birthdays, on anniversaries. And on those days, I know how it feels to be invisible, or worse, treated with disdain, even while you are serving someone.

I haven’t experienced everything. I’m not gonna say I know how childbirth feels (or honestly the vast majority of things women endure on a regular basis). I’m not gonna say I know what it feels like to be a minority, or to fight in a war, or to lose a limb, or to live in third world country, or to be betrayed by someone I love, or to be abused, or to be falsely imprisoned, or many other horrible things.

But even if I can’t exactly identify with what other people have gone through or are going through, I can try to imagine what it might be like, using my empathy. What would it feel like to lose a limb?

I can’t relate, but I can try to relate, and somehow that makes all the difference. I can help by sharing their misery just a little. Usually that means not trying to say something encouraging and “make it all better” or “look at the bright side.” Usually that means just shutting up and being there and listening.

And even though I may not be the most charismatic or cool person in the room, I can also least show a little empathy, and Rope reminds me that that is more important.

“Try not to become a man of success, but rather try to become a man of value.

He is considered successful in our day who gets more out of life than he puts in. But a man of value will give more than he receives.”

— Albert Einstein

So thought provoking and necessary to get our priorities right! I need to rewatch this movie asap!!!

Emerson said himself, "To be great is to be misunderstood." A hard truth I've had to accept is that the true artist can only really be born out of some degree of suffering - inner, social, etc.; the best art is made by those who have felt like outsiders in some way, because they are better able to observe society's failings in an objective, clearsighted manner. But it does feel like it comes at a cost, though I think it's a blessing - to have experiences that no one else will ever have. You have seen corners of lives that a lot of people don't get to see, so the grass isn't always greener (I try to tell myself).

The harder truth for me to accept is that some great artists who may carry this sense of isolation and deep sensitivity also happen to be charismatic celebrities, and I think this can cause a huge cognitive dissonance that leads to inner desperation and conflict (I think of Philip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Winehouse...).

I also think of Gatsby and Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby, to harken back to characters your mentioned in Hitchock's film; in the Great Gatsby, everyone has this sense that because Gatsby is rich, handsome, and popular from all his parties, that he is a lucky man. Then we see Nick Carraway, who may come off as a "nerdy dweeb" to that social scene. But we soon discover Nick is actually the most acute, sensible character in the entire story, while Gatsby has this hidden decadence. I'd like to think the same applies in real life... even those people we think are so great, so lucky, who have it all - they're still human, and therefore they still err.

Really enjoyed this!