I drive a taxi at night. I take the dirtiest, vilest people from place to place, wherever they want to go, on whatever awful mission they have planned. And I help them. The city is decaying, the people and the streets, a slow rot, a festering sore, a putrid landfill. Nighttime is the worst, because all the fiends come out. I let them ride in my cab, I take their money, I do their bidding. Night after night I do this, and the sickness is beginning to infect me too. I can't take it anymore. Someone has to clean up this mess. I'll go to any lengths, I'll do whatever it takes. I don't care. It has to stop.

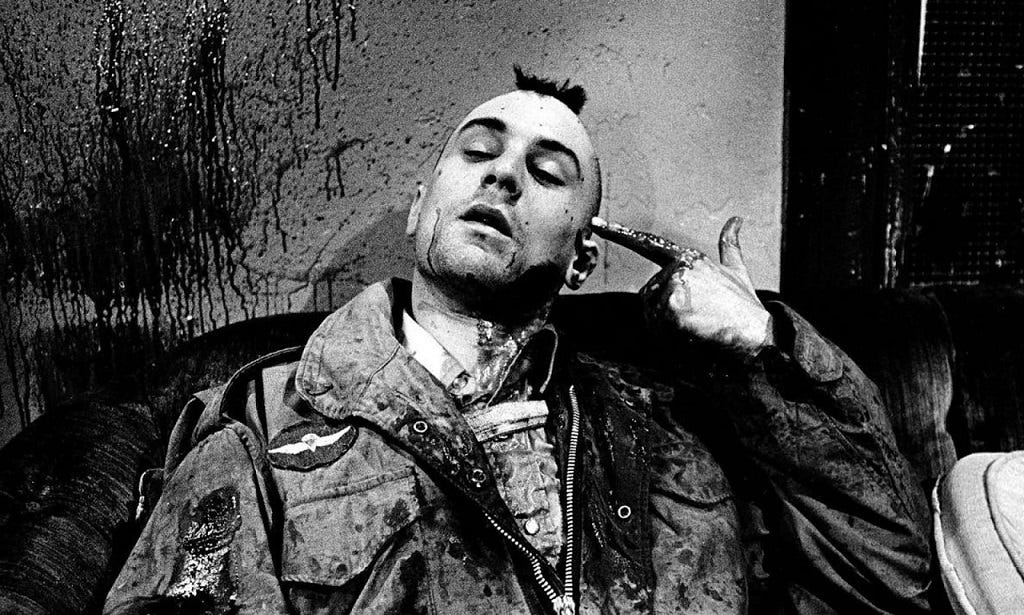

Picture this man, Travis Bickle, 30s male, the protagonist of Taxi Driver (1976). Imagine yourself as him— what it would feel like to have his job, to live his life, to wake up in the afternoon, and go to bed at dawn, an endless cycle of bleak hopelessness. Enter into the mind of this man, and feel the darkness overtaking him.

He says,

May 10th. Thank God for the rain which has helped wash away the garbage and trash off the sidewalks.

I'm workin' long hours now, six in the afternoon to six in the morning. Sometimes even eight in the morning, six days a week. Sometimes seven days a week. It's a long hustle but it keeps me real busy. I can take in three, three fifty a week. Sometimes even more when I do it off the meter.

All the animals come out at night - whores, skunk pussies, buggers, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies, sick, venal. Someday a real rain will come and wash all this scum off the streets.

Over the course of the film, Travis progresses from anxiety to depression to despondency, transitions from a productive member of society to a miserable imitation of the same miscreants he despises and execrates, descends from optimism and idealism into insanity and villainy. In his attempt to become a hero, to save the city, he becomes a monster, a predator of women and a murderer of unsuspecting innocents. At the end of the story, Travis is celebrated as that hero, but only briefly, only accidentally, and then he returns inevitably to his prison, his boat on the river Styx— the taxi cab.

Opposites of opposites

The world is not black and white. And it is also not just shades of grey. There are colors beyond the boundaries of our comprehension, further than our ability to describe, distal to the edge of our imagination. And this is where things get interesting— at the limits of humanity.

To approach these extremes, we have to grope and stumble through a hall of mirrors. We can't just look the opposite of any value, we have to look further— what is the opposite of the opposite? There are not just two sides of every coin coin, but dozens of different dimensions, and entire universe unto itself.

And the mark of a truly great story is the journey through this labyrinth, swinging from good to bad to better to worse, and beyond, until we reach the limit of humanity. The protagonist who goes to this distance may or may not succeed, in his attempt to overcome this final challenge, but it doesn't matter. The point is that his road has led him here, and his ultimate choice must result from a confrontation with this unavoidable problem, a choice which requires everything of him, and after which lies an irreversible change.

Travis Bickle takes this journey, which is what makes his story so engrossing. He begins as a productive member of society. A veteran, a hard-worker, providing a service that others need. He may be low-status, but at least he's doing something. And he stands in contrast to his opposite: the criminals and lowlifes who he transports, those who detract from the city and its people, whose only products are danger and destruction.

Travis is stuck in a dilemma, because he cannot quit his job, despite its poor conditions, and the evil that he abets, or else he will end up unemployed, a grey area in between the two opposites. An unemployed man is neither productive nor detractive to society, but we can guess which of the two he might be more likely to become next.

So instead, Travis resolves to be more than just productive, but instigative. He doesn't just want to follow the tide of society, but to redirect it. He recognizes a problem, and wants to do something about it. He wants to become a hero, that "real rain [that] will come and wash all this scum off the streets."

But though well-intentioned, Travis is misguided. He doesn't fully understand how the world works, how people interact, and what's possible. His motivations are also tainted with some selfish ambition. He doesn't just want to fix the city, but to be rewarded for it, ideally with affections of the girl he fantasizes about, and with adulation from the other citizens. And so in his apotheosis, in his attempt to rise about the muck in which he slogs, he becomes something even worse, something monstrous— he becomes a parasite, an abuser of women, a stalker, a creep, a killer. He becomes far worse than the mere criminals and prostitutes that he hates so much. But how did he get here? Only because he wanted to reach so high into something so good could he have had the potential energy to fall so low.

Ultimately, Travis fails to overcome his final challenge, and succumbs to the opposite of the opposite, be becoming worse than a criminal. But what makes Taxi Driver compelling is simply this: the journey through each of these turns, from good to bad to better to worst, and finally reaching the limits of humanity, to a dark and dejected end that none of us will ever experience, thank God.

Not all stories need to go to this kind of morose end, but great stories at least take us through that universe within the hall of mirrors, through opposites of opposites of its key value, until we reach the end of our imagination. What follows are a few more examples of films that do just that.

Alien

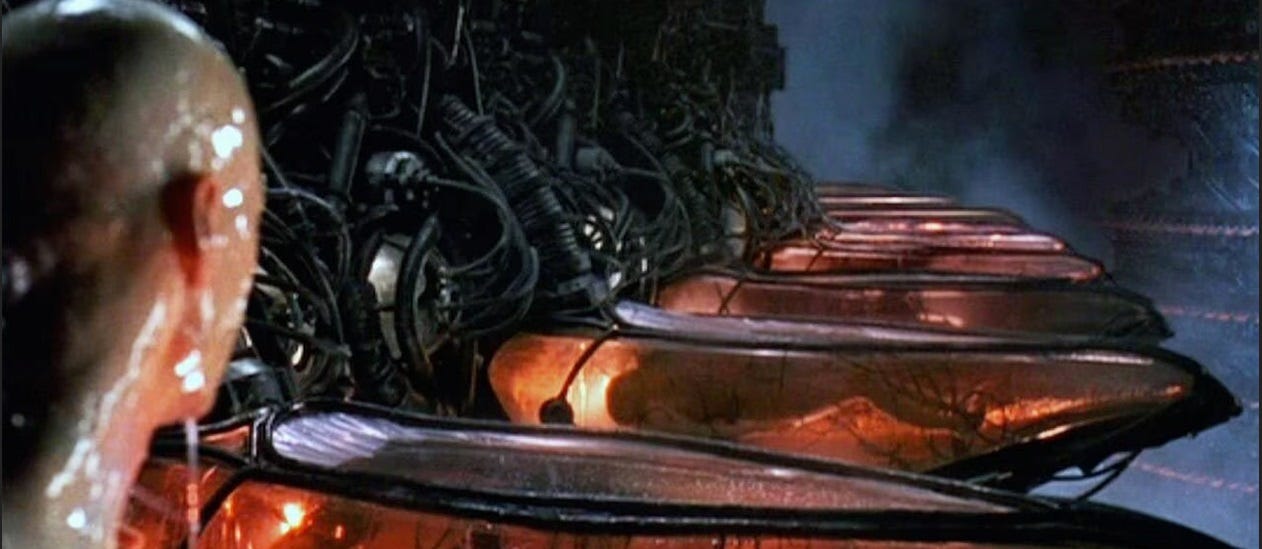

In Alien (1979), we have a monster that is the textbook definition of terrifying. But why? It is not merely its outward appearance (reminiscent of a gruesome insectile mutant), nor the fact that all of its natural qualities seem perfectly designed to kill humans (its exoskeleton is nearly impenetrable, and if somehow severed, its blood is so caustic that it melts through steel), nor its ability to lurk and hide and evade detection while mercilessly hunting the crew down one by one— none of these things in themselves are the source of the Alien's dreadfulness— what makes the Alien truly horrifying is what it represents...

At the start of the film, we see humanity thriving. They are at peak fitness, so advanced that they confidently explore the universe, looking for more planets to colonize, more resources to acquire. Each of the crew members is healthy and young and carefree. We see a version of humanity that is inspiring: no longer are we stuck on earth, struggling to survive, as we have throughout history.

A perfect opposite to this value would be a state of sickness, stagnation, and widespread death. A good antagonist would be a virus, a plague, or a famine (such as we see in a film like Interstellar). And so a mere monster seems a meager enemy compared to this... we have stopped fearing predators since prehistoric times, when we conquered the planet. But things are different here. For one, the crew of the Nostromo are isolated, and unskilled in combat, confined to tight quarters.

And more importantly, there's something different about the Alien... it is not simply a source of sickness and decay, but a perversion of these values. The Alien seeks to thrive, just as the humans do, but it does so only at their expense, by infecting them and using them as vessels for its children. This is the opposite of the opposite, health through sickness, flourishing through exploitation, and this is what makes the Xenomorph so revolting. It impregnates humans, sexually violating them, then festering inside of them until (without warning) one of its seeds bursts forth from within a live human, and the cycle begins anew, as a another Alien comes to life. The Alien represents the best instincts of humanity turned upon themselves— let the hunter become the hunted, the apex predator become the prey, the colonizer become the colonized, the great builder become a habitat for another...

The Dark Knight

In the Dark Knight trilogy (2005, 08, 12), we see Batman come to a crisis which costs him everything— his lifelong love, his reputation, and his power to do good— and in his absence the city is thrown into chaos and tyranny. But what causes this crisis? His confrontation with a force an incomprehensible force of evil.

Batman is a paragon of ethics, of the difference between right and wrong. While the police and the courts represent law and order, and the criminals represent disorder and the breaking of the law, Batman operates on a higher plane. His acts as a vigilante, beyond the limits of the law, but he also refuses to kill, even though that is often the just choice. Batman always chooses the ethically right thing to do, regardless of what the law says.

At first, Batman is confronted with criminals of increasing power and wickedness. Initially with Falcone, then with Scarecrow and Ra's al Ghul, and later with other crime bosses such as Lau. Each of these enemies challenges him, but he is able to succeed by drawing on his abilities and relying on his values.

But things fall apart when he meets his nemesis, the Joker, a villain so degenerate and unpredictable that all the other gang bosses fear him. Time and again, Batman fails to defeat the Joker because he cannot understand him. What does the Joker want? He does not believe in right or wrong. He doesn't care about justice or injustice, laws or crimes, wealth or poverty, life or death. He just wants to watch the world burn.

The Joker represents unbridled anarchy, and because there is nothing he wants, there is nothing the Batman can do to reign him in. Even when Batman succeeds in capturing the Joker, there are still more bombs going off in the city, predicaments that will cost Batman everything in order to stop them.

But the final twist of the knife is when we as the viewers realize the truth of what Joker says, that Batman is nothing without the Joker, and the Joker is nothing without the Batman, and that the two need each other. Which is why this particular story never ends, no matter how many renditions are told...

The Matrix

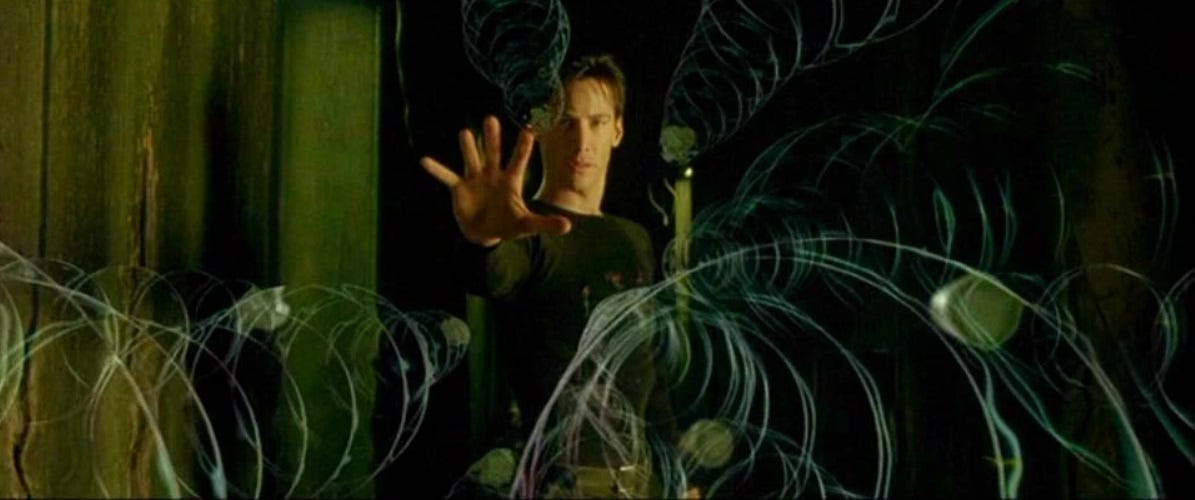

In The Matrix (1999), when we first meet Neo, as Thomas Anderson, he is bored to death, stuck in a dead-end corporate job, unable to keep up with his duties because they are totally banal and life-sucking. He is not technically a slave, but he is not a free man either, instead he is more like an indentured servant, a laborer who is kept endlessly employed, toiling to improve the capital and quality of life of another, without ever any real hope for his own.

But he soon realizes why he feels so empty— his whole life is a lie, and he and the rest of humanity are unwittingly enslaved to the machines, who use their bodies like batteries. Thus the stakes are not just freedom versus slavery, but worse than that. Humanity is under the spell of a slavery perceived as freedom. While they each chase their individual dreams, the machines harvest their organs and their energy, careless as to the results of their pursuits, which are as empty and meaningless as the world they live in.

But there are other opposites. Neo's primary antagonist is Mr. Smith, a relentless and brutally apathetic AI. Smith is not just a slave owner, nor a even taskmaster, but a bounty hunter, whose sole goal is to recapture those runaway slaves who have had a taste of freedom. Smith is an enslaver of those who are free.

And not only is Neo beset from the outside, but also from within, when he is betrayed by one of his own crew, Cipher, whose taste of freedom was quite bitter, and who wants to return to the comforts of slavery. He makes a deal with devil to sabotage Neo and the rest of the crew, all so he can return the blissful ignorance of slavery, happily deceiving himself into the lie that is the Matrix.

It is only when Neo accepts the truth of his freedom, that he does not belong to the machines nor the Matrix, and accepts this not just intellectually, but bodily, at the level of his soul, with every fiber of his being that he is finally able to overcome the restraints of his captors, the limitations of the Matrix, and the lies of the machines. Neo overcomes death.

And more than that, through the rest of the trilogy, Neo goes on to become the savior of humanity, setting everyone free, all while ending the war with the machines by making peace. The significance of his accomplishments is directly proportional to the magnitude of the forces he has to overcome.

Conclusion

Each of these stories takes us to the limits of humanity by exploring not just the good and bad of a specific value, but their opposites, and their opposites, and so on, until we have reached something entirely new and different, sometimes monstrous, sometimes wonderful, but always incredible. And like Neo, the protagonist of each story is finally faced with an irreversible and unavoidable choice, at the time when they are confronted with their ultimate crisis, and the quality of their choice is meaningful specifically because of the depths and heights to which they have traveled, and the immensity of their final moment.

Can you think of another story that does the same?

The original Blade Runner (1982) is a dead ringer for this sort of narrative. Might even say it’s the quintessential example of it.

I’ve just finished a great book “A Way Through the Wilderness “ and it’s all about opposites. After leaving bondage in Egypt the Israelites are experience the Wilderness which was on one hand a place of wandering, a place of hard teaching, a place of painful purification. But it was also a place of provision and protection. There was free food every morning, protection from the vipers. God was visible throughout the day and night in the pillar of cloud and pillar of fire. There was no doubt about which direction to move.

Yet when the wilderness training was over and the people of God entered the Promised Land, everything changed. “a land with large flourishing cities you did not build, houses filled with all kinds of good things you did not provide, wells you did not dig, and vineyards and olive groves you did not plant” (Deuteronomy 6:10-11)

In order to possess this land, however, there were aggressive military campaigns, cities walled and occupied by giants, fields to be tilled, planted, weeded, and harvested, marauders who waited until the crops were ready and then swept down to plunder and steal to be fought off