A Complete Human

The rare emotion of Courage

Is it possible for pets to love their owners? Would it be fair to even call it "Love"? What if pets are merely responding to Pavlovian instincts that tell them it feels good to be petted and to be fed and to play fetch, and that the owner tends to provide those things?

Unfortunately, it's impossible to know what animals "feel." We don't know if they are "conscious." And oddly enough, we don't even know whether other humans are conscious or not. This is called The Problem of Other Minds, and it essentially hearkens back to Descartes' cogito doctrine, where we can only truly be certain of our own consciousness. Perhaps every other human around us is just an automaton, and we are in a simulation, and they only seem conscious (q.v. The Matrix). Who knows?

But to speak practically, it does seem that most humans are conscious and that we tend to share various emotions like Love and Fear and Hope and Lust and Jealousy. We know this mostly because we can talk about it. Or we can use drama to act it out, and the audience recognizes it when they see it, and feel a visceral response.

Still, we honestly don't know if animals experience emotions. So then, what does it mean to be human? Though there are many possible ways to address that question, I want to look at just this one particular potential response to that question today: What if being human simply means experiencing emotions?

Though it's arguable that some emotions appear to be shared by animals, like Love, mentioned above, or maybe Fear or Anger, there do seem to be a particular emotions that are uniquely human.

For example, in a recent post, I wrote about the idea that "intelligence is the most dangerous thing in the universe," and that only humans (currently) can experience malevolence. Animals kill each other (and plants) all the time, but they do it almost robotically, on autopilot, as a means to an end, namely their own survival. It's never done merely out of jealously or outrage or revenge. Only humans do that.

We know that mammals experience a maternal instinct to nurse their young. Now we may never know the subjective quality of this urge, but we can infer what it may feel like because we experience something very similar. Consider Harlow's experiments with monkeys. Even babies experience a desire to be nursed, to be warmed, to be near their soft mothers, and they tremble and whimper and cower when unable to.

But so then, if you buy this argument so far, what would you say are the uniquely human emotions? And more importantly, do all of us get to experience each of them?

...What is a man // If his chief good and market of his time // Be but to sleep and feed? A beast, no more. —Hamlet

Sure, there is something different about humanity. Whether it be a soul, or divine appointment, or consciousness, or language, or something else. Though we are also animals, we are also something else entirely. Not merely incrementally better or smarter, but something qualitatively different — a singularity (q.v. "The Anthropocene."). We must be different than the animals in some way. Yes, we still need to eat and drink and sleep. We feel the desires for sex and friendship and family (though we can survive without them). But we also feel Creativity and Greed and Admiration and Disgust and Schadenfreude.

So is it possible that some people are more animalistic in their lifestyles, and others approach apotheosis? Would you not agree that someone like Da Vinci or Descartes or Shakespeare or Socrates or Musk somehow live a "higher" life? That perhaps they experience a richer or broader set of emotions than the typical e.g. plumber? (no offense). What does it feel like to paint the Mona Lisa and know in the depths of your soul that it will be eternally and universally celebrated?

The millions are awake enough for physical labor; but only one in a million is awake enough for effective intellectual exertion, only one in a hundred millions to a poetic or divine life. To be awake is to be alive. I have never yet met a man who was quite awake. —Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Let us consider for a moment what are the uniquely human emotions, and which of those are the rarest, or most difficult to experience. Perhaps Misery is one. Animals may starve and die, but only humans can feel Wretchedness at the thought that they could and should have more. Humans may feel abused, maltreated, ravaged.

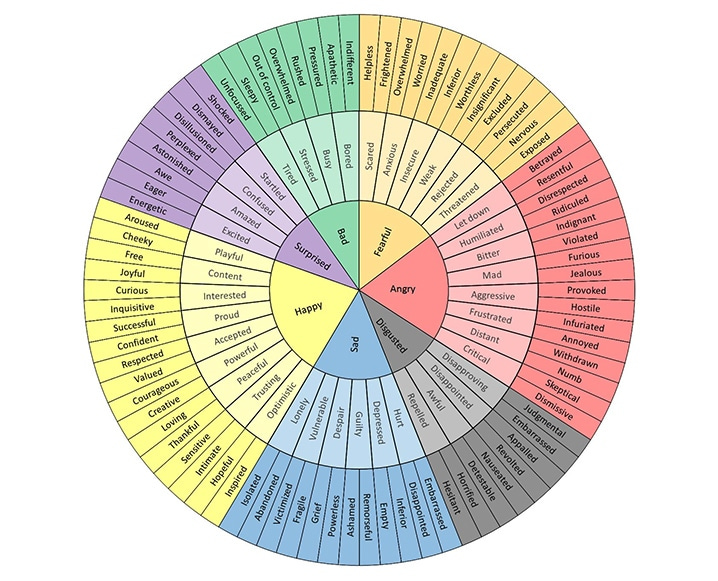

Below: an attempt to chart the spectrum of human emotions; probably a consultant’s work, which some company paid 6 figures for

Most of us have never had a day in our lives where we worried about a meal. But when I read stories of holocaust survivors, such as Frankl or Wiesel, I am stunned. I cannot even begin to imagine what it must be like to experience starvation for months on end. To stare death in the face. To stare evil in the face! And I hope and pray I never have to.

I have fasted from time to time and have been hungry, but I don’t think I’ve ever truly experienced capital H Hunger. The longest I ever went without food was 4 days (96 hours). It was hard, but I was never afraid. It was purely a matter of choice. At any moment, if I wanted to, I could walk to the nearest supermarket (or convenience store, or vending machine, or honestly any place that has a checkout lane), slap my little plastic rectangle on the screen, and acquire food of any shape, color, size, or flavor. And barring that, there are soup kitchens in every major city in the US. So truthfully, I have never truly experienced Hunger, nor the fear of starvation, nor the misery or wretchedness that accompanies it. And I truly thank God for that.

Don’t you know the devilry of lingering starvation, its exasperating torment, its black thoughts, its sombre and brooding ferocity? Well, I do. It takes a man all his inborn strength to fight hunger properly. It’s really easier to face bereavement, dishonour, and the perdition of one’s soul—than this kind of prolonged hunger. —Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

But Misery is not the only rare or difficult uniquely human emotion. Though I would be fine with never having to endure that emotion, there is another that truly fascinates me.

And what I think is audacious about this essay (and why I've taken so long to get to the point), is that I don't think everyone will agree with me. And so I hope you are following along with this argument, because it all leads to this point. Are you ready? Here it is.

I think most humans will never experience Courage.

There it is; I said it.

Now I'm not saying that most people are wimps. There are all kinds of moments in our lives where we have to be brave, where we have to suppress our fears and anxieties and press onward. Perhaps the most common examples that everyone is familiar with are the trepidations and butterflys-where-they-don’t-belong sensations surrounding 1) test-taking in school, 2) flirting with an attractive person, and 3) public speaking (or at least speaking in front of a group of people). These take bravery, surely. A little bit of guts and willpower? Absolutely. But Courage? I don’t think so.

And maybe I'm just getting into semantics now, but I don't think it would be fair to call approaching a cute person "Courageous." Nor would standing in front of your 3rd grade classmates and giving a book report about Hatchet.

I think Courage used to be more common when survival was not a guarantee, back when we had to defend ourselves from predators and predatory humans. Most obviously, in War. But also if you needed to kill a tiger or a bear that was going to waylay your camp and massacre your tribe. But since that seems really prehistoric, let's focus on War for now.

Charging into bulletfire is scary. I think perhaps the closest analogue would be paintball. Have you ever played paintball? I used to love it as a kid (and honestly still do). Now getting shot by a paintball hurts, and will leave a bruise, but it definitely won't kill you. And still, the fear of getting blasted by an orb of liquid at 40mph is enough to make your heart race at 2x your baseline bpm. Now imagine getting penetrated by a little metal shell which is designed to pierce your skin and organs and bones, and then fragment and cavitate and cause even more damage as it ricochets around your ribcage like a pinball. Or getting hit by a grenade, or a mortar shell, or an air strike. Yikes.

Charging into a battlefield is in my mind the definitive example of Courage in action. And that’s a key caveat— “in action.” It has to be demonstrated in the material world, not just the mental. Time and again, we've heard stories of soldiers who think they are heroes, but when the critical moment comes, they are cowards. It's not necessarily their fault. There's truly no way to know if you have what it takes until you try. The point is, thinking about Courageous acts is not enough. You actually have to demonstrate Courage in action to experience that emotion.

So then, barring War, are there other ways to experience this rare emotion? I don't know for sure, but I think so. I hope so. Because I don't think there will be any wars anytime soon (and I'm grateful for that). But I do want to experience Courage. So what does Courage look like in peacetime?

Ironically, perhaps Courage can be exemplified in a simulation of War, viz. sports. And this may sound silly, but I think that's because most of the time sports don’t really create the proper circumstances for this opportunity to arise. But as we've been talking about the dichotomy of Freedom vs. Limits, I think under the intense limitations that are created in elite sports, it just might be possible.

The impetus for this entire piece is a quote from an essay by David Foster Wallace, in which he profiles the journey of an amateur tennis player, Michael Joyce. What’s crazy about Joyce's story is that he has essentially sacrificed his life on the alter of tennis every day since he was about 6 years old. He has had no other objective in life but to be a professional tennis player. He has spent all of his waking hours either playing the sport, thinking about the sport, or doing some ancillary activity that relates to the sport (lifting weights, eating, stretching, watching film, etc.)

Above: Abraham sacrificing Isaac. Though in this case it would be more like Joyce sacrificing Joyce. But you get the point.

Joyce’s life is an absurd caricature of a typical human life, and though it's extremely limiting in some ways, it's also incredible in the opportunities it presents for him. This is a type of Freedom that none of us will probably ever experience, because we have not made the kind of sacrifices that Joyce has. Just as Courage in War requires us to risk the sacrifice of our lives, perhaps there is a Courage in elite sports that requires the same. Here's the quote:

Whether or not he ends up in the top ten and a name anybody will know, Michael Joyce will remain a figure of enduring and paradoxical fascination for me. The restrictions on his life have been, in my opinion, grotesque; and in certain ways Joyce himself is a grotesque. But the radical compression of his attention and self has allowed him to become a transcendent practitioner of an art—something few of us get to be. It’s allowed him to visit and test parts of his psyche that most of us do not even know for sure we have, to manifest in concrete form virtues like courage, persistence in the face of pain or exhaustion, performance under wilting scrutiny and pressure.

Michael Joyce is, in other words, a complete man (though in a grotesquely limited way). But he wants more. Not more completeness; he doesn’t think in terms of virtues or transcendence. He wants to be the best, to have his name known, to hold professional trophies over his head as he patiently turns in all four directions for the media. He is an American and he wants to win. He wants this, and he will pay to have it—will pay just to pursue it, let it define him—and will pay with the regretless cheer of a man for whom issues of choice became irrelevant long ago. Already, for Joyce, at 22, it’s too late for anything else: he’s invested too much, is in too deep. I think he’s both lucky and un-. He will say he is happy and mean it. Wish him well.

— David Foster Wallace, Tennis Player Michael Joyce's Professional Artistry as a Paradigm of Certain Stuff about Choice, Freedom, Discipline, Joy, Grotesquerie, and Human Completeness

Maybe you don't agree with Wallace’s line of thinking, but for me it is utterly gripping. I've played sports before, and I've competed on the championship stage (not anything Olympic, or even national level, but at least state), and I know what it feels like to feel the pressure of an audience and the stress of a trophy and the hair’s breadth distance between glory and ignominy, between bliss and heartbreak. I can only just barely imagine what it might be like to be a near-professional who has not just sacrificed a few years of high-school afternoons, but literal decades of his entire attention span and energy reserves on a daily basis. And then to put all that preparation and dedication to the test on the world stage, with either the possibility of eternal glory (at least in the world of tennis), or eternal anonymity, accompanied by a sense of complete devastation and the realization of a youth that was wasted.

Reading that quote grabbed me by the collar and gave me a vigorous shake, not only because of its lyrical beauty, but because it forced me consider whether I will ever get the opportunity in my life to experience raw Courage. And then it made me worry when I reckoned with the very real possibility that maybe I never will.

I don't know why, but Courage is one of those rare human emotions that I desperately want to experience. I’d be fine with missing out on Misery. And maybe Envy and Hate and a few other choice ones. Perhaps it is part of my makeup as a man. I identify strongly with my masculinity, and seek to exercise it whenever possible. To reach the end of my life without ever experiencing Courage would feel like a failure to me. I would not feel like “a complete man.”

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. — Henry David Thoreau, Walden

It's a bit too late in my life to become a professional athlete, so seeking Courage in that may prove fruitless. I might come close with the discipline of martial arts. I love Brazilian Jiu Jitsu and Muay Thai, and those sports can be pretty violent. I've competed twice now in BJJ, and I will say that the adrenaline I've gotten from competing in front of a crowd in that sport is the most powerful feeling I’ve ever experienced. It makes you dizzy. It makes you feel out-of-body. It's awesome and ferocious and terrifying and giddifying (?) and euphoric and dysphoric all at the same time.

It’s the closest thing to a life-or-death encounter that you can do on a regular basis. You are literally trying to deoxygenate your opponent’s brain until they go night-night, or twist their arm or leg to a point that physics and biology simply cannot accommodate, or make them thing that either of those are about to happen and so they tap out. And they are trying to do that to you. And their coach is on the sideline giving them helpful tips on exactly how to best dispatch you and leave you lying on the mats unconscious or nearly so. I’m dramatisizing a bit, but it’s not far from the truth. It’s scary, but it’s also invigorating.

Above: Me (on left) competing for the finals in Nogi in February. Kind funny how apelike I look in retrospect.

But I still don't think competing in martial arts is Courage, unless I were to really put my life on the line in an arena like the UFC, where blood is spilled and bones are broken and brains are concussed. So what then?

And finally I came to a conclusion which accorded with other plans and aspirations I have: Emergency Medicine.

I provided in my last post a few life updates, one of them being my decision to transition careers from being an Accountant to becoming an EMT. And I have many reasons for that, one of them being my lifelong desire to learn how to apply first aid and to help people in need. My ultimate goal in life is to help people on a metaphysical level, at scale, through the practice of writing (e.g. The Apocalypse), as that is how my life has been most dramatically influenced and improved. But I also want to help people on a physical, individual level through Emergency Medicine.

But more topically, I changed careers because I also want to experience Courage. And I think this is one potential avenue for me. I've only been working a couple weeks now, and my job is currently pretty intro-level, and I do mostly transfers of stable patients (they could decompensate at any time, so it's not just a Uber drive, but it's definitely a good place to start).

But eventually (and pretty soon hopefully), I want to run 911 calls. And in that world, you can get anything from an asthma attack or heart attack (relatively bathetic in the scheme of things) to a gunshot wound to the head or a multi-car motor vehicle accident. I imagine that running on scene to address a patient who is bleeding out and then trying to figure out how to help them will probably require Courage. It will demand composure under pressure, both patience and urgency, a combination of head knowledge and intuition and adapting to the uniqueness of each situation.

Oddly, Emergency Medicine doesn’t seem to share the same element of sacrifice that was entailed in War and Elite sports. There is definitely some sacrifice in the time I’ve spent studying and training, and in the Accounting career that I left (and its attendant salary), but I’m not putting my life at risk all the time (though definitely on some calls). Rather, I think it’s the amount of responsibility that is implied in the work, the pressure that is placed on me to act as appropriately as possible in order to try to save someone else’s life. Maybe it’s just that human lives need to be at risk in order for the opportunity for Courage to be presented. I don’t really know.

To be honest, I'm terrified of the moment when I respond to my first trauma call. But I'm also incredibly excited. I hope I get to experience Courage.

I'll admit that this pathway is certainly not for everyone. So then, what other avenues are available for us to experience Courage? Have you ever experienced Courage? What was it like?

Love this piece Grant. It’s an admirable to become an EMT and even more so when you fully explain your reasons why.

Recently I read that Jerry Seinfeld said that the human condition could be boiled down to one word: confront. Can you confront the fears in your life, face them instead of avoiding them, and overcome them? To me this means there are lots of opportunities to demonstrate courage. Now maybe that’s lower-case c courage and not Courage of battlefields and life-and-death situations. But I do think that modern life gives plenty of opportunities to show inner courage if you’re able to confront the things your mind most wants to avoid

Congratulations on your career change, and full props for competing in BJJ--impressive! How did you do in the final?

Until recently, most women displayed real courage by going through childbirth, often several times. You’ll probably see that as an EMT. Increasingly with epidurals and C-sections the courage factor is lessened somewhat in many cases but it’s still very impressive.

Greeks, who had a high standard of courage, considered childbirth a woman’s battlefield, her opportunity to display arete.

My intuition is that the birth rate is declining in advanced economies partly because we’ve demoralized young women and they’re fearful of giving birth.