Art is dead.

Above: AI imagined what the “Girl with the Pearl Earring” would look like if zoomed out

And along with Art, human creativity will be dead soon. And also our potential for human expression, and therefore our ability to connect meaningfully across time and space with people we have never met.

With the rise of AI-generated art, we will continue to create striking images, beautiful tableaux, and gorgeous portraits, but "behind the entire aesthetic of our civilization there will be a vast emptiness, a void communicating nothing."1

So says Erik Hoel, a compelling and captivating writer who uses his background of neuroscience to guide readers through fascinating explorations of the state of AI and how it impacts our understanding of culture, intelligence, and consciousness.

But is Erik right? Is Art dead?

Let's see.

Express yourself

"You have a terrible voice. Why do you even try to sing?"

"It's not about being good, it's about trying to be good."

"Well you're not good."

"I know."

"And you'll probably never be good."

"I know."

"So why do you try?"

"Because it's about trying."

".....well.....that's stupid."

No one has ever said this to me—thank God—but I hear those voices in my head every time I pick up the guitar and play.

I never learned music when I was a kid; it wasn't a big part of my household. I know a lot of Americans are forced to play piano when in elementary school, and that only backfires, causing them to hate music. So I guess I'm fortunate in that way—at least I approached music of my own accord. The only problem is, I started late. Very late.

So I'm bad at music. But that doesn't stop me from trying. And within my seemingly futile struggle to play there lies a fundamental truth of human nature—something so simple and yet so incredibly powerful that it just might be our salvation in the wake of this tumultuous future looming on the horizon, a truth that we cling to like stray wreckage as the swells rise and the wind stirs.

There’s no denying that change is coming with the rapid rise of AI. In fact, change is already here. But what does it mean for us? What does it mean, in particular, for graphic artists, who could be replaced— no, outperformed in some ways— by a teenager with nothing but a silly idea and access to the internet. With a simple text prompt, anyone can create images unheard of, undreamed of, unimaginable2.

If this kind of obsolescence can happen with art (and writing), what’s next? Will we all be replaced by robots?

As frightening as these premises seem, there's a comforting truth embedded in my yearning to play the guitar, despite my lack of talent or ability— an aspect of human consciousness so elemental that has been with us for tens of thousands of years, something that may even predate language.

As Erik points out,

“[There is a] close connection between art and human consciousness [that] is older than civilization itself. The early hand paintings from places like Chauvet cave, back to 30,000 BC are not merely images, but communications: 'I was here.'”

Above: a painting from the Chauvet Cave

This simple silhouette is both breathtaking and bathetic. On the one hand (excuse the pun), paintings like these are probably the least "artistic" kind of art there is, something that even toddlers do, as we dip their hands in paint and press them onto paper. And yet on the other hand, this specific exhibit is astonishing, because it's one of the earliest recorded forms of human expression, about twice as old as civilization itself (estimated around 10,000 BC). Before Homer, before Moses, before Gilgamesh, there is this hand, and a human mind behind it, desperately trying to tell us something.

Inside Out

But is it Art?

Ahh... the eternal question3. Something Socrates would probably ask his fellows in the agora, much to their chagrin and accompanied by chorus of groans 4.

Of course, the Chauvet hand painting is not aesthetically impressive, so it's not really artistic in that sense. But is that what makes Art, Art?

Whatever it may lack in technical brilliance, it nevertheless has an undeniable impression of authentic expression. There is within a simple splatter of paint (or blood?) something that signifies authorship, consciousness, design, and the presence of some person who is straining to say something. I can almost see him now—cold and shivering in the damp and darkness of prehistoric France, skittish at every slight sound of sough in the trees, a man who confused and confounded by the world which is incomprehensible to him, his days filled with the neverending task of survival, fighting with all his might to live another day, just one more day, and yearning, yearning, yearning to escape his inevitable (and likely imminent) death, to somehow transcend the present by leaving some sign, some mark upon the earth before it swallows him whole—"I was here."

Do we not also feel that same desire?

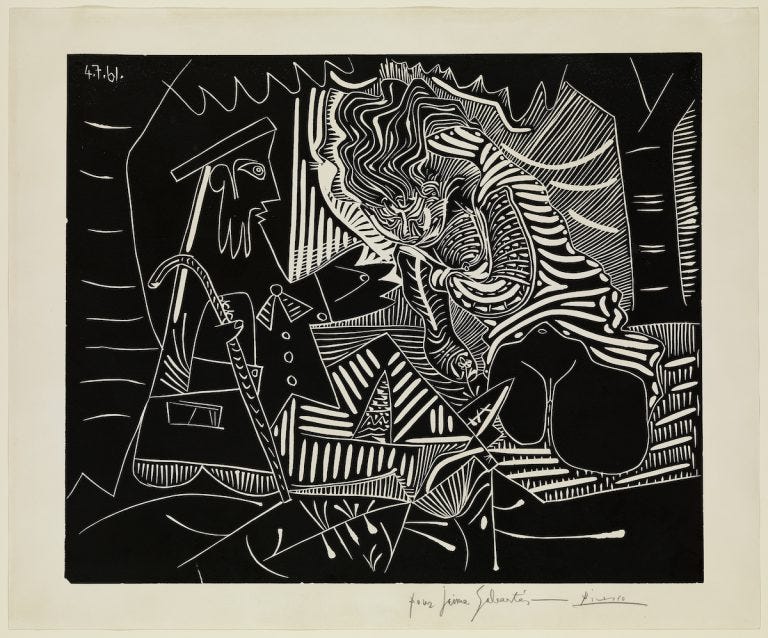

Despite the lack of "artistry," there is unquestionably still an artist. Perhaps more so than in something a million times more technically or traditionally beautiful, such as a picture languidly sketched by a tired Picasso in the latter years of a career so beset with success that his Midas touch had become mundane.

Above: Variation on Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe by Pablo Picasso (1961)

And thus the crucial distinction that Erik makes between the extrinsic and intrinsic properties of art.

Extrinsic qualities of Art are the aesthetics—the qualities we see with our eyes: color, texture, patterns; the interplay of light and shadows, a recognizable figure set within a discernible landscape, etc.

Intrinsic qualities of Art are the intentions—the qualities we cannot see, but rather the ones we discern in other parts of our bodies; how Art makes us feel; and all of this driven by the attempts from the artist to communicate his moods and emotions and desires, etc.

Above: The Two Fridas by Frida Kahlo (1930)

The image above is surreal enough to have been accidentally created by AI, but its significance is so much deeper than its striking appearance. Within and beyond the patterns of colors and lines, there is a story, a story of a woman whose heart was broken by her jealous and abusive husband, Diego Rivera. Moreover, the painting is superimposed upon a context that goes beyond this one image— there is the portfolio of her every one of her paintings, and how each of them ties in with moments from her life. So much of the beauty of Frida’s art is inseparable from her story—her woes, her aches, her nightmares, her miseries.

This is what we love about art.

Sure, the aesthetics are important. But the story is what we thrive on. Erik provides two perfect quotes that express this idea more beautifully than I ever could:

"The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance; for this, and not the external mannerism and detail, is their reality." —The Story of Philosophy by Will Durant (explaining/paraphrasing Aristotle)

"The aim of works of art is to infect people with the emotion the artist has experienced." —What is Art? by Tolstoy

AI certainly excels at the extrinsic qualities of Art, but does it have the ability to demonstrate the intrinsic qualities of Art? Probably not.

According to Erik, this how AI threatens the death of Art: we will have a proliferation of images that are aesthetically attractive and conceptually creative, but which are essentially soulless. No story underneath them. Royal robes placed on a manikin.

Patrons and Users

But that's actually the perfect example to show why I disagree with Erik's conclusion, because I think AI art CAN be used for expression and communication and connection between author and audience. And it won’t necessarily do so by supplanting traditional art, but by supplementing it.

In the same way that we don't create the clothes we wear, but still use them to express ourselves, we can use Art— all Art, whether created by a human or an algorithm— to connect with other humans.

Think about it— after every painting is completed, what happens next? Does it get rolled back up into the artist’s tube? No, it gets displayed, somewhere, by someone. For the budding artists of the Renaissance, their works were commissioned by priests, kings, aristocrats. And they prominently displayed them in their churches, or palaces, or villas. For though the patrons of the artists did not do the painting themselves, they financed them, and were ultimately responsible for their generation, their exhibition, their safekeeping. This is the same reason that record labels take most of the profits from their musicians, that executive producers of movies get their names first on the credits.

And though most of us are not wealthy enough to individually sponsor a famous artist, we still unconsciously display the art of certain creators every day—fashion designers. Every article of clothing you wear was intentionally designed by a human (or a team of humans), who probably think of themselves as artists of some sort, or at least aesthetes. Some of these fashion choices are more conscious and obvious—Gucci, Ralph Lauren, Jimmy Choo, Tom Ford, Bape, etc. Nevertheless, we daily express ourselves through the artistry of others when we dress ourselves (and even choosing to eschew fashion and wear only blue jeans or sweatpants is still a fashion choice). And yet how many of us have had a hand in actually tailoring those clothes?

We are users of Art, even if we are not the originators of it.

Still, there are some who make their clothes by hand (especially here in Boulder, Colorado), but how far do they really go? Does owning a sewing machine feel like cheating? Does buying premade fabrics instead of weaving them on the loom feel like cheating?

The crucial difference here is the creation of Art and the usage of Art. At some point, we are all both creators and users. When we assemble our outfit for the day, there is an aspect of creation. When we wear that outfit in public (or stay comfortably at home), there is an aspect of usage. And we can go further down the spectrum to creation the more we approach the raw elements of Art. We can sew our clothes, weave the fabrics, spin the yarn, grow the flax, mix the dyes, and so on.

Because if we really come down to it, AI art is actually just another tool that eases both the creation and usage of art. The only thing that changes is that now the production of that art has become more convenient and accessible.

Here's a perfect example: just last week I used AI-generated art to illustrate the climactic moment of a fictional story I wrote. In all my essays, I focus primarily on the words, but I also like to provide images every so often that depict a specific point, or evoke a critical sentiment from the text. Finding these images often takes a significant amount of time, but thankfully given the rise of stock photos and budding photographers, I'm usually able to find something similar to what I have in mind.

But sometimes it's very difficult to find an image that evokes or illustrates exactly what I want. And last week, I was really stumped. I sought for hours to find the perfect image for the climactic moment of my piece. And in theory I could have drawn it, if I had any talent for drawing. But I don't.

But here's the miracle. AI could draw it for me. And it took some prompting and playing around, but eventually I got it. And it was perfect. It was exactly what I needed. It conveyed everything I was trying to express. Perhaps not exactly as I had imagined it in my head, but in some ways it was better.

AI art allowed me to express myself, even if I only had a small part to play in its creation. I was more of a user, and somewhat of a patron (DALL-E is free for now), but still getting to participate in the creation of Art. As Tolstoy says in the quote above, I was able to emotionally infect my audience. Or at least I tried.

Artisan Artists

Erik says that the worst case scenario of AI art is the elimination of the profession of millions of artists, and thus the death of true Art—that Art with intrinsic qualities of expression, of authorial intentionality—leaving us with only blandly soulless, mass-produced art.

But I think traditional art will continue— only— it will go the way of cobbling.

There was a time when everyone who wanted shoes had to have them handmade by a cobbler. The cobbler was both a craftsman and an artist, sculpting leather to fit a person's unique feet (often asymmetric) and to meet their sartorial whims. But with the rise of the industrial revolution and assembly lines, shoes could be mass produced in a variety of sizes, much cheaper and much faster. So there was less demand for cobblers, and most of them lost their jobs.

But the art of cobbling is not dead. There is still a demand for handmade, bespoke leather footwear. Thus cobbling has become an artisan craft—something done by only a handful of experts, meticulously. It is labor intensive and expensive, but also more cherished by those who seek it out.

Traditional art will be the same way.

There was a time when graphic artists only had paint and canvas. But along came film photography, which nearly eliminated the need for life-like portraits. And then came digital photography, which removed the need for precise staging of shots. And then came iPhones, and pinterest and facebook and instagram. Mass proliferation of soulless productions.

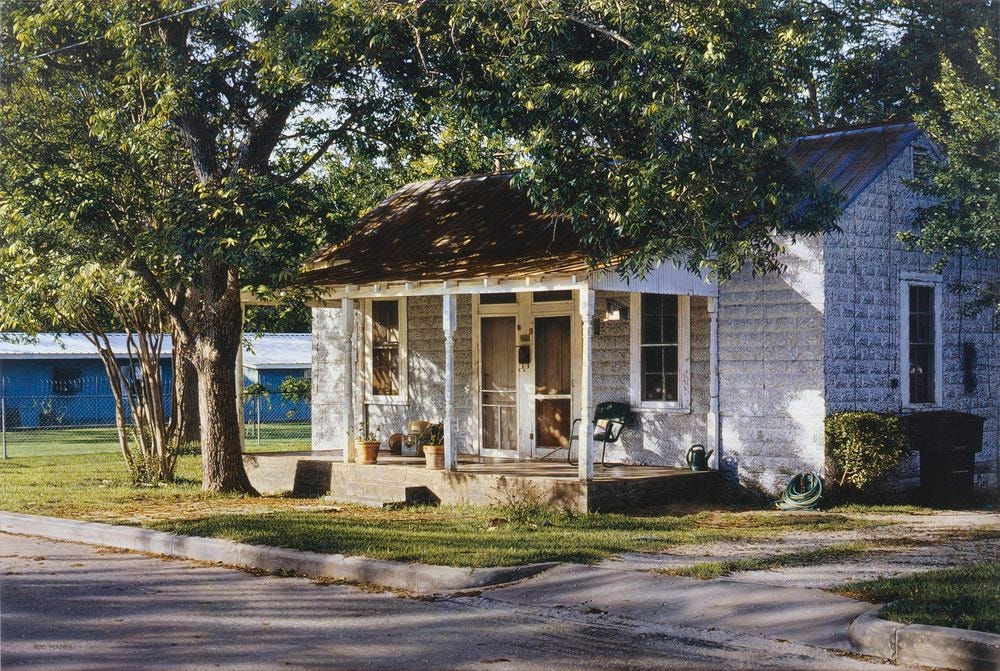

But there are still artists who use paint. Even though photos can capture a landscape more accurately, there is still a charm to the ardor required to paint the same scene (assuming photorealism is what we are evaluating here5).

Above: a photorealistic painting; House in Fredericksburg by Rod Penner

And that’s part of the whole endeavor, isn’t it? It’s about the desire to express ourselves, not despite difficulties, but because of them.

I love to play the guitar because it allows me to experience emotions that I simply cannot feel in any other way. My covers of songs are so much lower fidelity than their originals that it’s laughable. There’s no band of professional musicians playing with me, no drums, no piano, no backup singers. There’s no producer in the booth digitally mastering the sound levels. It’s just me, a warped acoustic guitar, and my vocal chords. But it’s raw, and it’s my own voice, and it’s authentic expression.

There’s something beautiful about my yearning to express myself, no matter how unimpressive the final performance is. Within those strained notes lies the same desire of the human who painted his or her hand on the wall of the cave in Chauvet, some 30 millennia ago.

And whether there is an audience or no, the very act of playing produces an emotional sensation that is infectious. I don’t know whether I’m playing the instrument or it’s playing me. It feels like surfing a wave that I myself created, but then lost control of.

I can still use professional recordings as inspiration, or even as expressions in themselves, when I send them to my friends. My attempts to play the guitar have not replaced the need for Taylor Swift. Likewise, when I want to illustrate an idea, I can use AI-generated art, and I can use hand-painted art, and I can use photographic art. I’m not going to try to draw anytime soon, but the possibility nevertheless remains.

This is not to say that there aren’t risks with AI, and that that massive change I described earlier won’t be devastating. We don’t know. The negative possibilities are worth considering, however unlikely, given the potential consequences. The problem is we just don’t understand it6.

Still, AI does not spell the death of Art, only the revelation of another form of accessible expression, one that will continue alongside the immortal craft of artisans and amateurs. Smallpox is an infectious disease that we eradicated from the planet in 1980 when the last known case was identified. But Art is an act of emotional infection that will never be eradicated. There will always be amateur artists, just as there are amateur actors, and photographers, and singers, and dancers, and writers.

I’m one of them. And guess what?

“I was here.” —Grant Shillings, 6/7/2023

Erik’s original essay, AI-art isn’t art.

‘When the flush of a newborn sun fell first on Eden's green and gold,

Our father Adam sat under the Tree and scratched with a stick in the mold;

And the first rude sketch that the world had seen was joy to his mighty heart,

Till the Devil whispered behind the leaves: "It's pretty, but is it Art?" ’

—The Conundrum of the Workshops by Rudyard Kipling

For the risks about AI, see this earlier essay:

Scary Smart

We easily forget that the world as we know it could end within the next 24 hours. There are still over 10,000 nuclear weapons primed and ready to be fired, and those nukes are owned by several different actors — eight nations, in fact: the United States, Russia, the UK, France, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea (and probably Israel). If any one of the…

I think this piece will be my go-to whenever I start thinking about this whole AI debate in the future. I really liked the whole thing, but especially when you showed the cave painting.

For me the appeal in AI is all about removing the boring tasks that don't have that "I was here" aspect to them, like a dirt texture for my video game

Thanks Jonas! It should be another tool in the toolbox that makes our lives easier, rather than a complete replacement of the craftsman