How to change your status

A look at the film Glengarry Glen Ross

"You call yourself a salesman, you son of a bitch?"

Welcome to the world of Glengarry Glen Ross, a film about the cutthroat work environment of real-estate sales in the 80s. This world has its own laws and its own internal logic— where terms like "Glengarry Glen Ross" sound like meaningless babble to outsiders, but make perfect sense to insiders.1

It's a place where almost anything goes: profanity, scathing insults, damnable lies, sexual seduction. As long as you're closing deals, no one cares how you do it. Money talks. Losers walk.

Status is everything, but can change in an instant. The best salesman get the best leads, the worst get their leftovers. Until there's an inversion: winners run on hot streaks that last for months and suddenly end in a crash of flames, going from the top of the hierarchy to the bottom.

And words are the supreme currency. These are salesman— professional talkers. They sculpt their speeches to hit just the right notes: at one moment smooth-talking a customer into a sweet deal, the next bitterly berating their own boss.

Glengarry Glen Ross provides a fascinating peek into the microcosm of these audacious salesmen, where the principles of regular life are turned upside down. Despite its bizarreness, their world tells us something significant about our own, specifically about status, speeches, and actions.

I'm going to give some spoilers, so if at any point this film seems interesting to you, I would go watch it and return here. But I'll explain enough that you should be able to follow along if you haven’t and don’t want to see it.

Power Dynamics

Glengarry Glen Ross is full of power dynamics, but this is not unique to the business world.

In almost all mammals, there is an obvious social dominance hierarchy. Those at the top have the first right of refusal for resources. The get to choose the best territory to make their home, the best access to food and water, the best choice of mates. Dominant individuals are able to act autonomously without the consent of other members. In contrast, those at the bottom are submissive and their behaviors are strongly influenced by others.

We are not beasts, but we are still animals, so we instinctively operate on these patterns, mostly on a subconscious level. We immediately identify where we stand in a hierarchy, and we act accordingly.

Just imagine what would happen if a famous movie star or a billionaire walked into the room you are in. How would you react? Would you know they were important simply by their presence, or by the way others react to them?

What about if instead of a billionaire, your guest were a crazed and dirty homeless person? Your reaction might be just as immediate, but very different.

Now these are the extremes of status, but the point remains: we instantly determine how we stand in relation to the people around us, and modify our behavior to suit that relation.

We would like to think we live in an egalitarian society where everyone is treated fairly, no matter their merit. But this is simply not true. Yes, things are much better than they used to be. We no longer have strict caste differences between patricians and plebians, royalty and commoners, free men and slaves. And now with the civil rights movements, all people are equal, no matter their race, color, creed, orientation, etc. At least, theoretically.

But old habits die hard, especially when they are ingrained in DNA. In every relationship we still subconsciously assign statuses. And this affects how we interact with each other, and how we see ourselves.

The good news is that these are changeable, although we may not always believe so.

Glengarry Glen Ross shows how quickly and unpredictably one’s status can shift. In this story, the cast of characters is very small: four employees, one supervisor, one consultant. In such a tight-knit group, people cannot hide behind their cubicle wall or their obscure job title. Everyone knows everyone.

The film has an all-star cast, and each of the characters play off each other:

Shelley Levene (Jack Lemmon), is the oldest salesman, and was once successful but is now struggling.

Ricky Roma (Al Pacino) is young, ambitious, cocky, and incredibly successful, although we don't yet know how or why.

Dave Moss (Ed Harris) is middle-aged, and mostly just angry. He is quickly becoming desperate.

George Aaronow (Alan Arkin) is also middle-aged, but mostly just worn-out. He is ready to give up.

John Williamson (Kevin Spacey) is their young supervisor, although he has no sales experience. The others don't respect him much, but he is a shrewd negotiator.

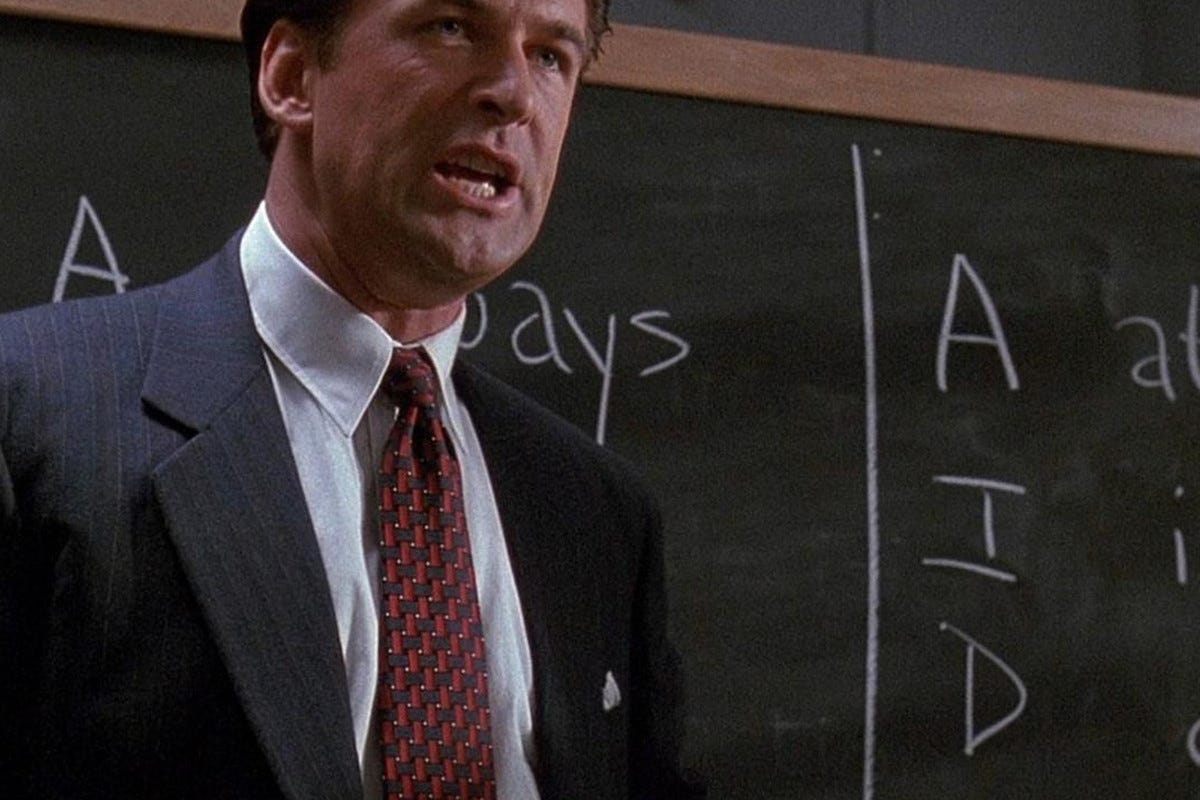

Blake (Alec Baldwin) is the hotshot consultant from headquarters, one of the most successful salesmen of all time. And he's got the egotism to match it.

The film begins with a very clear hierarchy: Blake is at the very top (so high he doesn't even belong), followed by the supervisor Williamson, and then the most successful of the local salesmen, Roma. The rest of the salesmen are at the bottom, but their order is unclear. At least for now.

The office is filled with whispers wondering what Blake is doing here. We soon find out— headquarters is very displeased with their poor sales record, and at the end of the month, the bottom two salesmen are getting fired.

Here is Blake explaining the situation, in the language of Glengarry Glen Ross:

“You can't close the leads you're given, you can't close shit, you are shit... hit the bricks, pal, and beat it, 'cause you're going out.”

What follows is the next twelve hours or so of the men scrambling to save their jobs and fighting over status. This is like any other social dominance hierarchy— the best salesmen get the best leads, the rest get the scraps. So it’s very important to them who is on top.

It's a fascinating premise and truly enjoyable to watch these great actors duel it out, their statuses fluctuating constantly.

A Personal Example

While their situation may seem unique, there are parallels in our own lives. We all belong to units of this size, such as our nuclear family, the starting lineup of a sports team, the members of a music band, a close circle of friends, or even our own group at work.

In these units, the roles are pretty well established and remain relatively static over time. We tend to view our statuses within the unit as unchangeable, but the film shows us that this is not necessarily true.

Here's a very simple example. When I first started training Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, I was a nobody. Literally, no one knew my name, and no one cared to learn it. That's because most novices leave after just a few weeks. The sport seems really cool at first, but after getting manhandled day after day, it starts to seem a lot less cool. So they quit. Totally understandable.

My only friend at the gym was the receptionist. Perhaps it was because he was the one collecting my payment each month. Still, he encouraged me to keep coming to class, and that one day it would get better.

It was hard to imagine this for the first several months. I would feel inspired after learning a new technique, only to have it fail miserably in execution. Why didn’t it work? Well, my more-experienced opponent already knew that technique, and a dozen counters to it. The real members, the ones who everyone knew their name, had been training there for years, sometimes decades.

It seemed hopeless. How would I ever improve my status, if every day that I got better, they got better too?

But I kept coming back, week after week, even when I was sore and depressed, and occasionally injured. I once cut my finger so bad I had to use duct tape to keep it sealed up, as all other tapes failed during practice.

Then one day, everything changed.

For the first time in six months, I submitted my opponent. I will never forget that moment. I used a Rolling Omoplata that I had just learned the day before.2 I have never once repeated the technique in the last five years, but it doesn’t matter. That day, it enabled me to win.

Instantaneously, my status changed. I was no longer a loser; I was a winner. At least once. And this was a categorical shift in my identity.

Things got better after that. Slowly, but surely, I started winning more often. People began learning my name.

Looking back, it is hard to relate to that former version of myself, the loser whom nobody knew. At the time, I thought change was hopeless, but persistence paid off. I didn't care how uncomfortable I was, how painful things got, I was going to get better. And eventually, I changed my status.

A Case Study

Glengarry Glen Ross shows us this same dynamic, although in a much more dramatic setting. While it would be interesting to simultaneously analyze the fluctuating statuses of all six members of the film’s core cast, it is easier to look at just one example: the relationship between Levine (the oldest salesman), and Williamson (the supervisor).

After Blake gives his scathing presentation and tells the men they are fired, they immediately begin complaining and dissenting. Levine confronts Williamson, asking for better leads. Williamson turns him down, so Levine resorts to begging, lowering his status. When this fails, he resorts to bribery, which Williamson entertains, lowering his own status. Williamson makes a counteroffer, which Levine rejects— a point for him. Williamson then walks away from the deal, forcing Levine to start begging again, even groveling. Finally Levine accepts a pitiful deal from Williamson, but the new hope fills Levine with confidence. Until Williamson demands the payment now, which he can’t afford, so he walks away completely deflated.

In just one short scene, we see the power dynamics shift erratically. But that’s not the end. In the climax of the story, we see their relationship go through even more revolutions.

Later that night, the office is robbed by Moss (the angry and desperate salesman), and Levine is in on it. However, the next morning, Levine returns to the office exuding confidence after closing a big deal, ending his losing streak, and securing his continued employment. In his newfound arrogance, he starts abusing Williamson, lecturing and demeaning him, seemingly with no remembrance of the begging and bribery he resorted to just last night.

“You can’t run an office. I don’t care. You don’t know what it is, you don’t have the sense, you don’t have the balls. You ever been on a [sale]?…

What I’m saying to you: things can change. You see? This is where you fuck up, because this is something you don’t know. You can’t look down the road. And see what’s coming. Might be someone else… Might be someone new, eh?

Until, almost imperceptibly, Levine reveals that he is aware of the robbery. Williamson then turns the table once more, interrogating him. At first, Levine is embarrassed but tries to play it off, acting confused. Then he shifts to denial, laughing at Williamson, mocking him. But soon he realizes that the jig is up and he has been discovered, and so he surrenders. Williamson then becomes the cruel one, revealing a long-held hatred for Levine.

Over the course of just these two scenes, the relationship between these two men changes drastically from being thick as thieves to the bitterest of nemeses. Watching it is like watching a wrestling match where the two competitors are caught in a rolling tumble— you never know who is going to end up on top.

In Glengarry Glen Ross, power dynamics turn on a dime. Our relationships may not be as volatile as those of the characters, but the story nevertheless reminds us that relationships are malleable, that individual statuses can change, no matter how permanent they may seem.

My status at the Jiu Jitsu gym certainly did not change quickly. At times, it felt like an eternity. But ultimately, it did change.

Speeches

The second insight we gain from Glengarry Glen Ross is that speeches don’t change status, they communicate status.

We would like to think we could persuade someone if we just make the right argument, or choose the right words, or use the right tone of voice. But as humans, we make our decisions about status, trustworthiness, and likeability much more simply and more quickly, sometimes in less than a second.3 So then, why are we so preoccupied with speeches? And why do the characters in the film spend so much time delivering speeches to each other?

For example, when Blake is presenting to the salesmen, we watch as he continues to reiterate the same point over and over again— they are not fulfilling expectations, and they need to either shape up or ship out. The point of his message is clear from his first few sentences, yet he continues.

“You can’t play the man’s game, you can’t close them, then go home and tell your wife your troubles. Because One Thing Counts In This Life: Get Them To Sign On The Line Which Is Dotted. You hear me…? I know your war stories, I know the bullshit excuses that are your lives. What do you know? What do you know…”

And interestingly, this extended rant doesn't seem to further convince or motivate the salesmen. In fact, just after he finishes, they are already complaining about him or reasoning away his arguments. So then, why did he drag on so long? Why do we do the same?

There are a number of reasons. Sometimes we think as we speak (not always recommended). Sometimes we like to hear ourselves speak (I know some people like this, and it's very annoying).

But the most pertinent reason is that we use speeches to communicate our status, like a peacock spreading its feathers or a gorilla beating its chest. A bold, successful person like Blake is going to speak boldly. He doesn't become a winner just because he sounds like one. Moreover nothing the salesmen say is going to change his status.4 He already made the money. And they are already gonna lose their jobs. His long rant just drives home this point and allows him to flex.

Therefore, while the speeches in the film are interesting and enjoyable to watch, they ultimately don't carry any weight, at least in terms of changing someone's mind. The only way to do that is to provide new information, or to demonstrate a change of behavior.

Ethics

Finally, Glengarry Glen Ross shows us that ethics are not absolute, but relative. By ethics, I mean a code of conduct, something that defines which actions are acceptable and which are not. And these are partly defined by values, by which I mean the things we deem important.

During his presentation Blake reveals the values and ethics of the company, which he exemplifies:

“I made nine hundred seventy thousand dollars last year. What did you make?... Nice guy? I don't give a shit. Good father? Fuck you. Go home to your kids. You want to work here? Close.”

In the firm, It doesn’t matter if you’re a good family man, if you are a nice guy, if you act honorably; the only thing that matters is whether you close deals. That’s why Blake is on top, and the other salesmen are at the bottom. As a result, he can speak to them like children, like dogs, with no repercussions. No one can argue with him, and all their protests are invalidated.

“What's your name?”

“Fuck You, that's my name. You know why, Mister? 'Cause you drove a Hyundai to get here tonight, I drove a sixty thousand dollar BMW.”

The firm's sole value is sales, and as a result, its ethics are quite tolerant. Almost any type of behavior is acceptable.

Levine lies through his teeth to customers, saying he is the president of the company, in town for one night only, that he is going to award them a “prize,” that the properties are sound investments. None of this is true.

Moss robs the company. To protect himself, he coerces Aaronow (the weary salesman) to join him.

But it gets worse. Through most of the film, the entire office has been alluding to Roma, the top local salesman, and we are left wondering how he does it, the secret to his success. And we finally find out, as we see Roma seduce a customer in order to close a deal, then lie to the customer when he tries to break the contract—which is not only illegal, but highly unethical—at least to us.

But in this world, it's totally acceptable. The fact remains that Roma closes deals, so he is above reproach. He is on top, and will remain on top as long as he continues his sales streak.

In a famous line, Blake tells the salesmen:

“You know what it takes to sell real estate? It takes brass balls.”

To translate from the language of Glengarry Glen Ross into our own, what he means is that the salesman have to live by his code of ethics. They have to give up the values of being a good parent, or a good partner, or a good person, and instead acquire the sole value of sales.

The truth is that every social unit we belong to has its own values and its own ethical code. Sports teams want to win, bands want to sell out shows, work groups want to get the job done, families want harmony. Sometimes the values of our different groups conflict with each other, and we are left confused as to which actions to take, which are acceptable, which are optimal.

The is why it is crucial we determine for ourselves our values (what's important to us) and our ethics (what we are willing to do in order to achieve them).

If we don't do this on our own, the groups will decide for us by default, and we will adopt their codes of ethics. And we may not like who we become.

Conclusion

At times, the world of Glengarry Glen Ross is absurd, completely different from our own. And yet, we can learn a lot from it.

First, our actions speak louder than words. Long speeches and eloquent arguments typically do not change our status on their own. In the film, the only thing that mattered is sales. If the men sold more, their status increased. Then their manner of speaking changed accordingly.

The same is true of my Jiu Jitsu journey. It didn’t matter how nice I was, or how badass I acted, or how much I proclaimed my dedication to the sport. I simply had to show up and get the reps in and keep getting better.

Secondly, the movie reminds us that the ethics of our group(s) define our own ethics— what activities are acceptable— unless we choose to define them beforehand, on our own terms. In the film, all kinds of immoral and illegal activity is allowed, even encouraged, while being a good family member is deprecated.

In the gym, winning was important, but persistence was even more valued. It takes at least ten years to become a black belt, and no amount of wins will get you there any quicker. Other values, such as courtesy, honor, and protecting each other, were paramount. You could be a black belt, but if you were an asshole, or dangerous, no one would want to train with you. I have since come to accept these principles as part of my own ethical code, but that was a conscious decision.

Finally, Glengarry Glen Ross shows us that our role in a relationship, our status in a group, may seem fixed, but it is actually malleable. In the film, these statuses change rapidly, mostly because the men believe it is possible.

As I’ve already said, my status at the gym did not change as quickly as I wanted, but it did eventually, and it was all the more worthwhile once it did. And this change occurred particularly because I continued to live out their values, by prioritizing persistence over comfort, by putting my pride to the side.

Please give me anonymous feedback here!

Footnotes

The title of the film comes from two real estate developments: Glengarry Highlands is the new opportunity that all the salesman want to sell; Glen Ross Farms was a previous opportunity that sold very well just a few years ago. The characters refer to these opportunities often, but usually just using the first part of the name.

The Rolling Omoplata

For more on this, see Blink by Malcolm Gladwell, or look up “thin-slicing.”

While there is some truth to fake-it-til-you-make-it (AKA the Pygmalion effect), this takes a very long time. And it doesn’t always work.

Excellent work! The phrase “Birds of a feather flock together “ fits here. I believe it starts with defining your values and beliefs and then choosing people and environments that support those. Otherwise there can be no genuineness. Status is not constant but character can and should be…

This is a wonderfully structured article! I really liked how you weaved together the topic of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu within the context of this film (which I have never heard of until now). I have my white belt in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu and always lost, but I'm sure it's gratifying to win. In a tangential way, this movie has very similar traits to American Psycho and Mad Men (the modern day male duel, but it's just white-collar businessmen with penchants for greed, lust, and power).