Love and Gravity

The surprising argument of Interstellar

Interstellar (2014) is an exhilarating science-fiction epic, and one of my favorite movies of all time, but it is also more than that; underneath its action-packed plot lies a powerful and surprising argument about love, an argument all the more compelling due to its basis in the unlikely marriage of philosophy and astrophysics.

The situation

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

— Dylan Thomas, 1952

At its heart, the story of Interstellar is about the impending death of humanity, and our desperate struggle to survive. The poem above, repeatedly read by Professor Brand (Michael Caine), serves as the summation of this theme.

Set sometime in the near-future, the world of Interstellar is dying, as the earth slowly rots before our eyes. One by one, each of the major staple crops succumb to a virulent disease known as blight. First wheat, then okra, and finally, the only food that remains is corn, and we are told that that too will soon die.

In response, NASA launches one final mission, a desperate attempt to escape the earth and continue human life elsewhere. There are two alternatives to accomplish this: Plan A, to launch a massive satellite from the earth, where humanity could survive in space (sort of like the international space station), and Plan B, to travel through a mysterious wormhole to a distant part of the galaxy and establish a colony on a new planet. Both options are incredibly unlikely to succeed, full of their respective complications, risks, and requisite sacrifices. Thus the characters are left with a fool's choice, and the outlook for humanity is bleak.

As a result, what sets Interstellar apart from most other stories/arguments about love is its stakes. It's not just about a boy and a girl,1 but about the fate of all of humanity, forever.

The argument

At the climax of the story, the protagonist, Coop (Matthew McConaughey) has traveled through the wormhole with his team, and they must choose on which of two possible planets they should attempt to start the new colony. They only have enough resources to go to one. How to decide?

Dr. Brand (Anne Hathaway)2 wants to go to the planet where Dr. Edmunds landed, while Coop wants to go to the planet visited by Dr. Mann (Matt Damon). The data is equally promising for both planets, with only a slight advantage going to Dr. Mann's.

Before they decide, Coop criticizes Dr. Brand, concerned that her secret love for Dr. Edmunds is influencing her preference for his planet. Coop thinks her emotions have clouded her judgment. We would expect her to protest this attack, but surprisingly, Dr. Brand actually leans into this position:

BRAND

Yes. That makes me want to follow my heart. But maybe we’ve spent too long trying to figure all this with theory -

COOPER

You’re a scientist, Brand -

BRAND

I am. So listen to me when I tell you that love isn’t something we invented - it’s observable, powerful. Why shouldn’t it mean something?

COOPER

It means social utility - child rearing, social bonding -

BRAND

We love people who’ve died ... where’s the social utility in that? Maybe it means more - something we can’t understand, yet. Maybe it’s some evidence, some artifact of higher dimensions that we can’t consciously perceive. I’m drawn across the universe to someone I haven’t seen for a decade, who I know is probably dead...

Coop, though he studied engineering in college, is nevertheless merely a pilot on this mission. All the other members are highly technical scientists, including Dr. Brand. So it comes as a shock that he of all people would argue the case of science, especially since we know that he is strongly motivated by love for his family.

But as he fumbles for a logical explanation for love— that it is simply an emotion humans evolved to feel because it predisposes us to be better at raising children and cooperating with others— these sterile and weak rationales fall flat in contrast to Brand's passionate plea. She concludes:

“Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space. Maybe we should trust that, even if we can’t yet understand it.”

This one line sits at the heart of the entire film, and serves as its core argument.

The antagonist

Unfortunately, the full force of this argument is hard to appreciate, mainly because there is an unspoken assumption underlying it. While it is ostensibly a philosophical argument, its true weight and significance comes from its context, the context of the entire story of Interstellar and the problems therein.

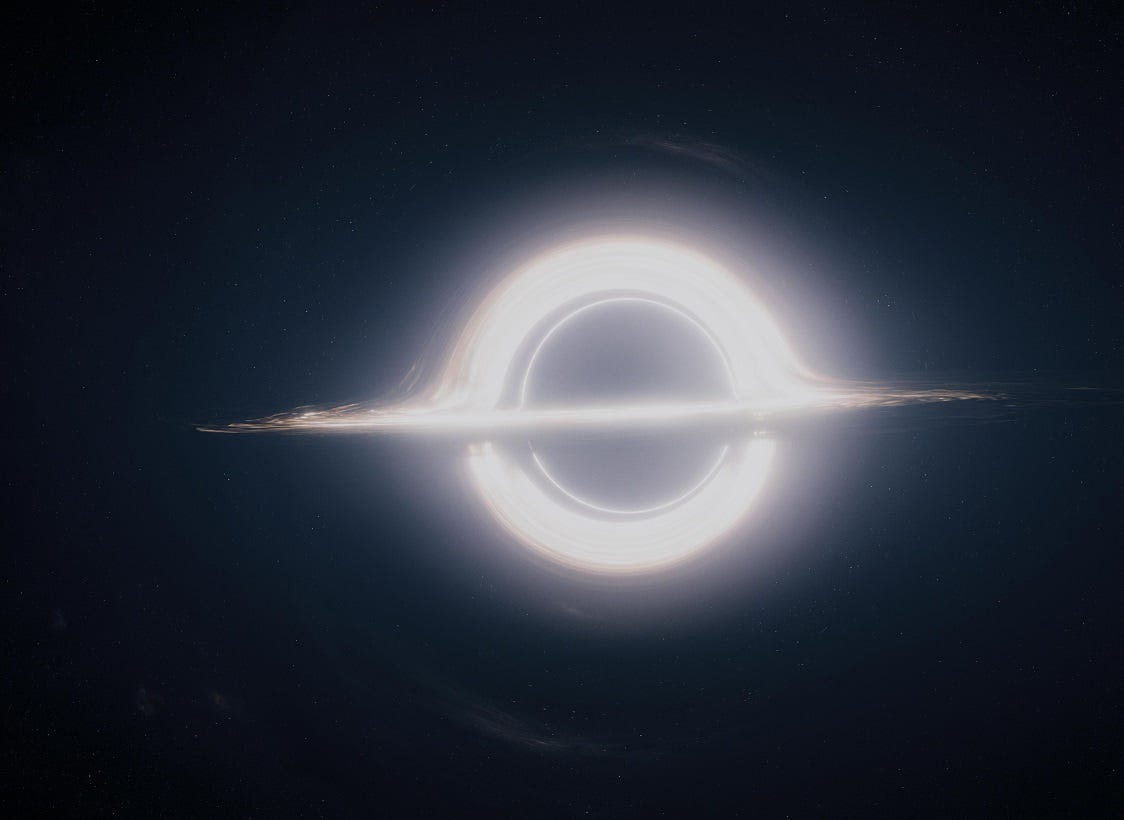

While it appears that the primary antagonist of the film is blight— the disease destroying earth's crops and forcing humanity to flee— the true source of antagonism is actually gravity. Gravity is the mysterious force that has been silently leading Coop, and NASA, on their journey through the galaxy.

First, a gravitational anomaly was responsible for the accident that ruined Coop's career a decade ago, destroying his hopes of fulfilling his life's purpose as a pilot. But it was also what led him to start a family, and what gave him the object of his love— his children.

Years later, gravitational anomalies led Coop to discover NASA's headquarters by inexplicable lines of dust left in in his daughter's room, which spelled out the coordinates of the base. If he had never found NASA, he would not be a part of this mission, or these decisions. Moreover, NASA may not have ever made it this far without his expertise.

Furthermore, gravity is what led to NASA's discovery of the wormhole which serves as their miraculous opportunity to start a new colony in another part of the galaxy, the goal of Plan B.

Gravity is also what caused the disaster on Miller's planet, which was too close to the black hole / wormhole, nearly killing everyone on the mission, and forcing the dilemma above.

And lastly, gravity is the one thing that is preventing Plan A from succeeding, the one thing that has stumped Professor Brand for years from solving his equation, a problem which, left unsolved, will leave everyone on earth stranded, including Coop's family, awaiting an inevitable doom— the only question of whether they will starve or suffocate first.

No, the true antagonist of the film is gravity; it is what catalyzes each of the characters into action, it is what drives the plot along, providing both opportunities and crises, gravity is what forces the characters to make the ultimate choices at each of their respective climaxes.

But wait a moment, what is gravity?

The science

Recall from high school physics that gravity is simply the attraction between two objects. The greater an object's mass, and the lesser its distance from another object, the stronger is gravitational pull. Denser objects have a higher gravity due to higher ratio of mass-to-radius. We don’t witness this attraction much on earth because there are other forces in play, such as electromagnetic, friction, and subatomic forces which have a stronger effect than gravity.

But in space, these competing forces have less influence, and the objects are larger, which is why we observe gravity having such a powerful effect. This is why the moon orbits the earth, why the earth orbits the sun, why the milky way galaxy revolves around its central star cluster.

Put simply, gravity is an attraction between two objects. And as we watch Interstellar, we learn along with the rest of the characters that gravity is also the one force that is able to affect other things across space and time. This is why, towards the end of the film, Coop is able to send messages to himself and to his daughter, across the galaxy, back in time.

But to return to Dr. Brand's argument: When she says her unforgettable line, if we are aware of this unspoken assumption about gravity, we are hit with a wave of insight. What else is love, but an invisible force of attraction?

She says, "Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space." And within the context of the story, we know that she is also alluding to the fact that gravity is also capable of transcending time and space, that she is saying that perhaps love is gravity, that it is not just an evolutionary quirk or a funny little human feeling but in fact a fundamental force of the universe. Love, like gravity, is simply attraction, and yet despite this simple explanation it has incalculable consequences— both the revolution of planets and the formation of galaxies— and it may in fact be responsible for the existence of reality, of everything we see, and the motivation for everything we do.

The alternative

Because the other unspoken question, the question that is also tugging at us throughout the film is this— What is it all for? Why do we love? Why do we want to survive? What is the point of human existence?

We see this enigma unfold when Dr. Mann betrays Coop's team, and by extension, all of humanity. This is all the more ironic because everyone speaks of Dr. Mann so highly, saying that he is the smartest, and noblest, and bravest man of all time. It is this reputation that convinces Coop to visit his planet, ignoring Dr. Brand's passionate plea.

But it is revealed that Dr. Mann, despite all his virtues, is ultimately a coward, and he lied about the viability of his planet, all so he could save himself. He explains,

"A trip into the unknown requires improvisation. Machines can’t improvise well because you can’t program a fear of death. The survival instinct is our single greatest source of inspiration…

I tried to do my duty, Cooper, but the day I arrived I could see this place had nothing. I resisted the temptation for years ... but I knew there was a way to get rescued.”

So Dr. Mann finds justification for his treachery (and cowardice) in his survival instinct. He is willing to doom them all so he can live a little longer.

But this raises the question— What's the point of Dr. Mann's survival if the rest of humanity dies out? What does he hope to accomplish?

Survival is indeed a powerful motivator, but ultimately an unsatisfying answer to the question of the meaning of life. If the point of life is to survive, then we will always fail, because survival is impossible. We will always die, sooner or later. We don’t just live so that we can keep on living. This line of reasoning makes no sense; there has to be something else.

Instead, Dr. Brand's argument serves as a much more compelling answer— we live in order to love.

But what is love? It is this inexplicable force: no one can tell you what it is, but you know without ever having to be told. It is invisible, intangible, immeasurable; yet we can perceive its influence on us, as it irresistibly attracts us across space and time, to our friends, our families, our partners, even to people who are dead, or not yet born. Love has inspired the greatest works of art, has stirred the founding of empires (and their destruction), has instigated wars (and armistices), and, if we are honest, has affected each of our individual lives in seemingly more powerful, though subtler ways.

This explains why Coop has such a difficult time deciding to go on the mission in the first place. He knows that if he leaves, he may never see his family again, but if he stays, they will all die. He ends up leaving them, not because he wants to survive and save himself, but because he loves them and is willing to do whatever it takes to bless them, even if it means giving his own life.

And he is asked once again to make the same choice at his climax in the story. Though he initially ignores Dr. Brand's argument for love, at the end of the film, we can tell by his actions that he does indeed believe what she says, as he sacrifices himself by plunging back into the wormhole. It is only by a miracle that he survives, but the point is still clear— love wins.

We may not ever understand exactly how gravity— or love— works. Both still baffle scientists. And philosophers. And also singer-songwriters. And also every single person who has ever lived. But maybe we don't need to comprehend it; maybe that's not important. Maybe all we need to know is that there is something deeper going on here, something bigger than us, something cosmic, something eternal, something we can rely on when all hope is lost, and the way forward seems impossible and unknowable.

Footnote:

Like my story from two weeks ago, which, interestingly, uses a similar analogy to the argument of this essay.

It’s important here to distinguish between the father, Professor Brand, played by Michael Caine, and the daughter, Dr. Brand, played by Anne Hathaway.

I haven't watched Interstellar in a long time and this was a treat to read, more with your added insightful commentary. Knowing you're a sci-fi fan, what did you think of Dune 2?

Another great thought provoking essay. Love found gives us the highest of highs and love lost the lowest of lows.