In 2014, Margaret Atwood published a novel that no one alive today will ever read. She put the manuscript in a time capsule, which is sealed for 100 years. It cannot be opened until 2114. She won't tell anyone what the book is about. And she will never make a dime from it. So— why?

Atwood wants to transcend time. But can you imagine the difficulty of the task— how do you create a work of art that will be relevant 100 years from today? We don’t even know what tomorrow will hold. Put yourself back just ten years ago to 2014, when her novel was finished— back then did you have any idea what 2024 would look like?

So then, trying to forecast ten times that amount, to 100 years in the future, seems absurd. Will humans still be around in the 22nd century? If so, will we still read books? Will anyone speak English, or will we all just speak Mandarin Chinese? Or, what if people just simply forget to retrieve Atwood's book from the time capsule?

Legacy

I’d like to do something like that. I’d like to create something that lasts 100 years. Most people have that desire too— that’s why we start families. We hope that our children will grow and flourish, and they will have children, and they will have children, and so on. Maybe our families will grow so large that they will become clans, or even dynasties.

Perhaps we aren’t that rash our ambitions. But our ancestors were: Genghis Khan, Abraham, the Medicis, the Caesars, the Wei and Ming dynasties... And if not in families, others throughout history have sought to leave their legacy by founding cities, discovering continents, setting world records, and constructing cathedrals, coliseums, skyscrapers...

But how can I build something that will last a century when I everything I do is ephemeral— a Greek word which means "for the day only." Here today, gone tomorrow. All my creations seem to evaporate like morning dew.

I want to impress you. I want to write something that would catch your attention, make you drop what you’re doing, ignore any potential interruptions. I want to grab you by the shoulders and shake you. To reach down and touch your heart. I'd like to teach you something you'll never forget. To make you feel something you've never felt before. I want to do all these things because I've experienced them myself—from reading the golden words of other writers.

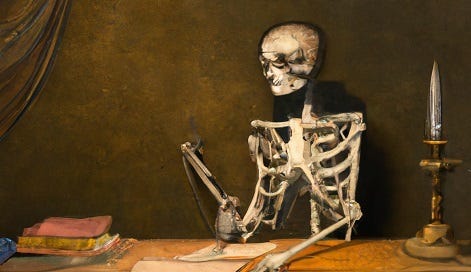

But it seems insurmountable. I don't even know how to start. Call it writer's block. I’ve been staring at a blank page for days now. Dozens of false starts, aborted drafts, dumb ideas. The fact that this essay even exists is itself a miracle.

I have so many things I want to say, so many ideas that I'd love to tell you, about all the books I’ve read, or movies I’ve seen, or things that happened to me, and what I’ve learned recently. And if you and me could just sit down and chat, I could talk to you for hours and hours. But none of that is publishable. Not yet. It's too amorphous, too unformed, too discursive, unedited, insufficient at this time. I tell myself I need to study the topics more. I need to wrestle with the ideas and prove them out. Otherwise I'd just be wasting your time. And mine.

So what can I do? How can I write something that stands for ten decades when I have only been alive for three? I know so little about the world and the people in it. And the more I know, the more I realize how much I don't know. And when I try to communicate what I do know, it all sounds limp and obvious and boring.

And when I compare myself to my heroes, my inspiration, the portraits on my wall, when I look into the unblinking eyes of the writers who first moved me to write—

David Foster Wallace, who published his first novel at 22, then went on to write his masterpiece at age 31 (the age I am today), a book that shocked the world and sold over a million copies

Alain de Botton, who has written over a dozen bestsellers, and even founded a school, which holds sessions around the globe

Rene Descartes, who before he turned 40 catalyzed the discipline of Philosophy which had laid dormant for almost a thousand years

Henry David Thoreau, whose experiment in the woods in his 20s is now taught in almost every school in America

John Milton, whose Paradise Lost took over 40 years to write, during the last 20 of which he was blind

— when I compare myself to these, and others, all my efforts seem pitiful and vain. How can I ever hope to approach something so lofty? Am I just recklessly unrealistic? Am I a fool?

Long gone

But then again, this is a fruitless perspective anyways. In 100 years, it won't matter if my words remain, because I will be dead. At the end of the day, who cares?

A common piece of advice given to young people is to imagine yourself attending your own funeral, listening to all the eulogies. What would you want your parents to say, your brothers, your colleagues, your rivals?

This is an interesting thought experiment, but on the other hand, it is also totally useless. I won't be at my own funeral; I won't have to listen to other people talk about me; I won't care. So why should it matter to me whether people read my writing after I’m long gone?

Perhaps it all stems from the innate desire to live forever. To escape death. To transcend time. My body may decay and rot, but my ideas, my personality, and my passion may survive and live on, in the hearts and minds of those I touch. Is that not a form of eternal life?

"But do civilizations die? Again, not quite. Greek civilization is not really dead; only its frame is gone and its habitat has changed and spread; it survives in the memory of the race, and in such abundance that no one life, however full and long, could absorb it all. Homer has more readers now than in his own day and land. The Greek poets and philosophers are in every library and college... This selective survival of creative minds is the most real and beneficent of immortalities." - Will Durant

I think this theory may explain the motivation to leave a legacy, but it still doesn't justify it. If I were to live my life each day with the dedication and fervor necessary to build something that lasts that long, I just might be able to do it. Maybe. But I would probably hate my life the whole time. And it would be a bad bargain, because I would have wasted my life in the process. My one life. That seems inverted. Not just a road of good intentions that leads to hell, but a road which itself has become hell.

Love

Consider if we parented that way: if our focus was on creating dynasties rather than loving our children. Yes, we could scheme, and plan, and create ornate routines to best bring out their capabilities, we could manipulate them, force tutors and coaches upon them, arrange marriages for them... but we've seen how that turns out. All the political intrigue in history— take for example all the families in Europe and the constant violence and diplomatic marriages and concubines and bastards and patricide and fratricide and war and... We would be missing the forest for the trees.

No, the only way to start a family that lasts is to love each child with all our heart and soul, with all our ability. To love them as individuals, not as some brick in a building, just part of a bigger plan. The focus cannot be the legacy, at least not directly. We can keep that goal in mind, but there must be something else along the way.

And let's not forget that all of those authors I idolize—they each had their own issues, which were not insignificant:

Wallace struggled with depression his whole life, and committed suicide at 46

de Botton is probably the loneliest and saddest writer I've ever read— part of what gives his writing so much feeling, but also what makes him unenviable

Descartes died from pneumonia at 53 from the whims of a petulant Swedish queen

Thoreau, for all his bragging about his meager diet and stoic lifestyle, died from bronchitis at 44 from spending too much time in the rain

Milton was denounced and harassed by the state, his first wife left him, his second wife died after two years of marriage, and, as said, he was blind for the last 20 years of his life

And the list goes on. Dickens had OCD, King was a drug addict and alcoholic, so was Hemingway (who also killed himself)

In that light, maybe it's not worth it at all. The whole transcending time thing. At least, if I do it for the wrong reasons— if I want to impress, if I want to be rich, or famous, or celebrated, if I want to seem smart, or clever, or wise.

Conclusion

No, creation has to be for the love of the thing only. It has to be about ecstasy, not legacy. It's the same with parenting as it is with writing, or any kind of endeavor. It has to be real.

It's just like kindness. People intuitively know when you are using them for something, or whether you genuinely care. Whether you are listening, or just waiting for your chance to speak. And I think people can tell too— when you write, or create, or build—whether it's contrived or authentic. Whether you are doing it to show off, or you are trying to really communicate something, to express yourself.

The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one's real and one's declared aims, one turns, as it were instinctively, to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish squirting out ink. - George Orwell

The only way to build something worthwhile is to enjoy the building of it. To care so much about the process that the end product doesn't matter. To become the fastest at the 100 meter dash, you have to run a million miles. You'll never get there if you just want to cross the finish line in first place in some faraway fantasy.

And it has to start with the first few steps. Baby steps. Each essay always feels like complete garbage at the start. Every idea feels like a dumb one (Most are). But eventually, after getting it on the page, after working on it for a while, it gradually starts to turn into something. And it gets better and better each time. It's not easier; no, it's never more comfortable; just better.

When I look back at my essays from six months ago, I cringe. At the time when I published them, I thought they were marvelous. Now I see how terrible they are. And that's encouraging, because it means I'm getting better. I'm seeing more clearly. But I never could have gotten here if I had never published in the first place. If I had never put myself through the agony of creation.

For me, writing has to be about love, not about legacy. One is controllable, the other is not. And if I make it all about success and hate the process, I might never get there, and then it will all feel like a waste. And it will be. But it doesn't have to be that way.

When I think about how people will see my work in a hundred years from now, all I dare to imagine is that some kind of cultural historian will be trying to understand the psyche of people from our generation. I'm afraid that's the best I can do for anyone that far into the future, be research subject 4325 out of millions of other people who post stuff online. It terrifies me a bit.

I feel like I would be incredibly lucky to even be able to do some good for people right now.

Loved this piece, you really spoke to me. Thanks for writing it. <3

Oppps that ended before I was finished. Anyway, it’s like you said about people knowing when you are genuine. They feel it when you care and when you’re just going through the motions. Jesus said to take one day at a time, don’t worry about tomorrow. Granted he was referring to worrying about physical needs but I think it also applies to your message about worrying about being remembered. Each day is a blessing so I believe we are to make the best of each day anyway we can, through our work, relationships, etc.