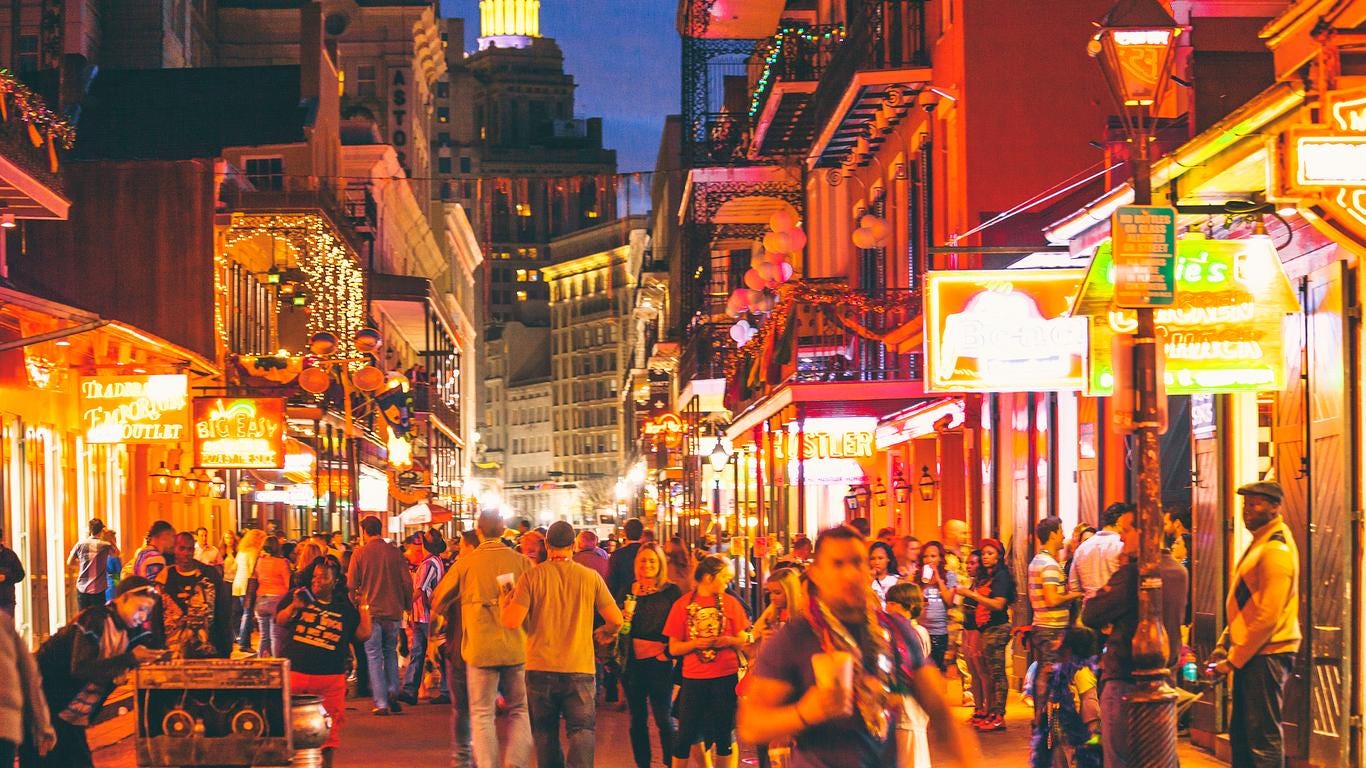

It is civil twilight, that ethereal hour just after the sun has dipped below the horizon, but has yet to relinquish its grasp upon the earth. Above, the sunset is a backdrop of quiet serenity, exquisite beauty, and stately nobility, which contrasts sharply with the chaotic energy now bubbling below, a witches' cauldron of noise and activity, here on Bourbon Street, in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Something significant is starting here, a timeless ritual as old as the race of men, echoed endlessly all around the planet ever since we first embraced the comforting warmth and glow of flames from a fire.

Despite the frenetic commotion below, the heavens rearrange themselves gradually, almost casually, suggesting their familiarity with these sort of worldly patterns that repeat on a daily basis for millennia. The sinking sun sends its last rays into the stratosphere, but they are caught, intercepted, and then scattered by the clouds, wisps and husks and shells and pillows strewn across the sky, the sunbeams now diffracted across millions of vapor particles, their light now diffusing into prisms of indescribable colors, evoking sensations of citrus and smoldering coals, honey and blood, fire and gemstones.

It is Saturday evening in July, the peak of Summer, where the days are lavishly long, and now—more than ever—this resplendent hour of dusk seems to stretch on with the timelessness of a dream. If you glance away for even a moment, the colors have once again shifted, the clouds rearrange themselves in a lethargic game of musical chairs, and the tapestry has been resewn once more in a distinctly new design. It is brilliant.

But down on the street, the lighting is of a different character— glass tubes filled with electrified neon gas, bent into the shapes instantly recognizable as cocktail glasses, women's legs, cowboy hats, and beer steins. Old-fashioned gas streetlamps serve more for mood than proper illumination. Great morasses of people strew back and forth across the street, up and down its length, stirring and whirling and mixing, eddies forming from a tidal movement of bodies not dissimilar from the delta of the nearby Mississippi River. There is a frenetic energy here, and a static charge is slowly building from all the activity.

Also, it's loud.

There is the sound of rock and roll riffs emanating from a corner bar, windows flung open in the summer heat and humidity, swirls of steam escaping as the perspiration evaporates from hundreds of warm bodies pressed in together, moving and bobbing en masse to the music. These sounds merge with the unmistakable synthesizers of 80s disco, blasting from another bar across the street. Slightly quieter due to the distance, but still distinguishable, are the rapid beats of 808s and snare drums, signifying the classic beat of millennial rap.

And that's just the music. There is also a chorus of voices from several different parties in the vicinity. There is subdued bass of a passionate conversation between men arguing a critical point about sports, mixed with the soprano shouts of a pack of sorority sisters, sprinting in skirts too short and heels too high for that particular speed of locomotion. There is the hawking of waiters holding large menus, arrayed in black shirts and black ties and (incomprehensibly) black aprons, urging passerby to sample their specials, secret concoctions designed solely to seduce those who are—to be honest—already well enough intoxicated. If these pedestrians were not already inebriated by the drinks and the drugs, they would nevertheless still be addled by all the activity, the noise, the lights, the presence of so many other people, the merrymaking, the celebration of it all.

Incongruous

And there I stand, bewildered.

What am I doing here? I clearly don't belong here. I am incongruous. And yet no one notices me. They each speed along their route to whatever destination calls them for that segment of the evening.

I feel out of place because I spent last night sleeping alone in the woods, my view of the stars unobstructed by the practicality of a roof or a tent. I have been alone with my own thoughts and the sounds of nature for the last 24 hours.

To transition from that world into this scene is... jarring.

I feel like a stranger here. And this is a good thing, because the astonishment I feel creates a distance between me and everyone else, allowing me to examine the entire event from a detached point of view.

I begin to wonder... why do we do this?

This is not something unique to New Orleans. There are streets like this in every major city around the world.1 And even in the small towns, there is a main street, a place where tired workers come to spend their coin and recreate a bit. Every time I visit a new city, I like to find these streets and walk them, to get to know the place. And though I don’t fit in here right now, I’m not a stranger to these scenes—I've been to my share of parties. I'm generally an introvert, but I too feel the magnetic pull to engage in this kind of revelry every so often. It drains me, but also recharges me. Odd.

But still, what causes this phenomenon? Why do we feel the need to gather in such massive crowds of strangers, to throw ourselves headlong into such a disorderly environment, full of festivities and gaiety and liveliness? Why are we drawn the comfort of clamor? Why do we seek celebration?

I have a theory— it's because somewhere, deep down in our subconscious, we are all afraid of the dark.

Why do all kids fear a monster in the closet, or under the bed? Why, even as adults, do we get goosebumps when we walk through an unfamiliar place in the dark and hear a bump in the night?

It's the same reason why dogs are naturally good at begging for food, why they recklessly race after rodents, why they bark when they think their owner is in danger. It’s because it worked. A long time ago, their ancestors did it, and survived. So now they do it, without ever needing to be taught.

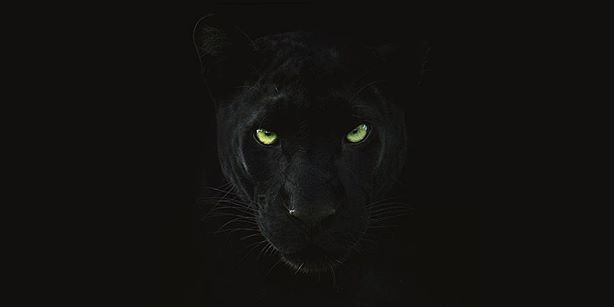

Like them, somewhere, deep down in the brainstem, where the most basic biological instructions are stored—breathing, heart rate, hunger, urination, sex drive—there is also a primal fear of the predators who lurk concealed behind the curtain of shadows.

Prehistoric Parties

For the revelers on Bourbon street, there is no conscious thinking about why they are here tonight. It's simply "fun to go out."

But I've just come from the wilderness, and I know something that most of us have forgotten—it's scary out there, alone and in the dark. If you don't believe me, try spending a night in the woods by yourself, somewhere deep enough into the trees that you can't hear cars. At first, it's fine. But then you hear a creak, a rustle, a scratching. What was that? Probably nothing. But you hear it again. Is something out there? Don’t move an inch. Your ears stretch to listen for more… silence. Then your imagination starts to run. Is it a tree about to collapse on top of me? Is it a bear going to rip me to shreds? Is it another human who wants to kill me and steal all my stuff?

These fears are clearly unreasonable on paper, but out there—they are quite compelling. They feel serious—deadly serious.

Somewhere deep in our DNA, the body knows what the mind has forgotten (or has never learned): there are things out there that can and will destroy you. Nature is merciless. Our ancestors scraped by just barely. Life was hard. They spent most of their time feeling hungry. And there were other animals hungry for them—a lion or a tiger or a leopard. And if death didn't come from them, it came from a crocodile, or a snake, or a scorpion. Or poison ivy, stinging nettle, devil's thorn, fever tree. But the worst of all these threats was rival tribes— other men, who look like us, move on two feet just like us, but will gladly beat our brains in with a blunt object in order to take our bread.

In prehistoric times, most of our (brief) lives were expereinced as shivering cold, gnawing hunger, and creeping dread— except for a certain occasion— the festival celebration. These celebrations were quite similar to our modern Bourbon street, but instead of neon there was the bonfire, instead of trap music there was the ritual dance and song, instead of gossip and smalltalk about jobs and dating and sports, there were war stories and dramatic reenactments and tribal mythologies.

Our ancestors couldn't afford to celebrate all the time, but certain milestone events were deemed worthy: the completion of a successful hunt, the culmination of harvest season, a major victory in battle, or the changing of the seasons. For these events, they could afford to feast, to burn through the stockpile of wood, to shout and sing and dance the night away. It was the prehistoric party.

And so there's something deeply reassuring about noise and lights and commotion—it means safety. It is the comfort of clamor. If there is a celebration, it means there isn’t a war right now. It means that for the next few hours, for the rest of this evening, we can relax and revel and rejoice. We aren't going to die tonight.

That's why we like to go out. It’s not just for “a good time.” After a long week of cautiously keeping our heads down, creeping along quietly, working hard to provide for ourselves and our families, it is during the celebration that we can finally unwind.

False Flicker

But we don't all like to go out every weekend—so what gives? I enjoy it too, but I don't make a habit out of it. So what do we do instead? Instead of lighting the bonfire, we turn on the flickering screen of the television set. The noise and commotion are now provided by actors, characters, explosions, soundtracks; we get immersed in those stories rather than the mythologies of our people.

Above: me playing video games late one night. I don’t look terribly happy.

It doesn't even have to be a particularly large “fire,” as long as we are close to it and it fills up our visual field. Now our phones do the same thing. Americans spend about seven hours out of every twenty-four looking at screens.

In some ways this is fine. I'm not saying that we all need to head to our local version of Bourbon Street every weekend and dive intp the debauchery. At home, at the touch of a finger, we have access to amazing works of art in cinema, literature, and video games. There are incredibly immersive, entertaining, and edifying experiences to be had through the power of the internet. We can even connect with others around the world, in a limited way.

But there's also something lost when we stay in our homes and turn on the screens, however entertaining or artistic the program is. 2

There’s just something different about being physically around other people—friends, family, or strangers—and being involved in the commotion. It doesn’t have to be getting drinks at a bar; it could be dinner at a restaurant, a meal at home, a play at the theater, a stand-up comedy routine, a live music concert, a local parade, a service at church, a picnic in the park, a professional sports game.

We are liable to forget how terrifying the darkness is, but we all remember the true comfort of the festival celebration when when we sit around a campfire or a hearth in the wintertime. There's something that inevitably draws us in, that makes us feel safe. We feel the urge to talk, to swap stories, to hear another's voice. Deep down, we remember the comfort of clamor.

Humans are social animals. We need to be around others, to engage with them, to talk and share and laugh and interact.

We may no longer fear predators that lurk in the dark, but a different disaster may be upon us—a more subtle death—the creeping annihilation of easy indulgence, isolation, and loneliness.

Footnotes

Chat GPT gave me a list of 29 similar streets. The last one is a street in my current home.

6th Street (Austin, USA)

Khao San Road (Bangkok, Thailand)

Lan Kwai Fong (Hong Kong)

Temple Bar (Dublin, Ireland)

Rue Sainte-Catherine (Montreal, Canada)

The Strip (Las Vegas, USA)

Beale Street (Memphis, USA)

Kings Cross (Sydney, Australia)

Istiklal Avenue (Istanbul, Turkey)

Passeig de Gracia (Barcelona, Spain)

Myeongdong Street (Seoul, South Korea)

Reeperbahn (Hamburg, Germany)

Rue de la Huchette (Paris, France)

Pub Street (Siem Reap, Cambodia)

Calle Uruguay (Panama City, Panama)

Nathan Road (Hong Kong)

Clarke Quay (Singapore)

Oudezijds Voorburgwal (Amsterdam, Netherlands)

The Promenade des Anglais (Nice, France)

La Rambla (Barcelona, Spain)

Harajuku Takeshita Street (Tokyo, Japan)

Bourbon Street (Cape Town, South Africa)

Oxford Street (London, UK)

Vaci Street (Budapest, Hungary)

Karl Johans Gate (Oslo, Norway)

Pushkinskaya Street (St. Petersburg, Russia)

Haji Lane (Singapore)

Granville Street (Vancouver, Canada)

Orchard Road (Singapore)

Pearl Street (Boulder, Colorado, United States)

I wrote about this strong pull to stay at home a few weeks ago:

Stay in your homes

When Virtual Reality becomes mainstream, we will no longer travel. VR presents the opportunity for us to enjoy an unlimited buffet of all kinds of fantastic experiences, all from the comfort of our couches. These experiences can be grounded in reality (such as visiting foreign countries, or meeting with friends in virtual chat rooms), or they can be surr…

I’ve always thought that the draw of Bourbon Street was escapism. An attempt forget about our problems and our loneliness: Alcohol to forget the pain and let go of our insecurities and the crowds to give us a sense of camaraderie and connection.

Excellent stuff, Grant. Crowds as an antidote to being alone in the woods made a lightbulb go off for me. Well done.