The short story “Mr. Squishy” by David Foster Wallace depicts one of my most vivid nightmares.1

It's about a man trapped in the most boring meeting of all time, a man who is realizing that not only is the meeting meaningless, but so too are his job, his company, his career—nay, his entire life.

What makes the story so terrible to me is that it forces me to reckon with this idea of futility. And to see how it applies to my own life.

Futility is a Latin word that literally means "leaking." It was used in Roman times to describe something like a cracked clay pot—a worthless possession, for it cannot be used to hold water, or to cook, or to store food. Worse still, it will never be useful, because clay pots cannot be fixed.

This is my biggest fear—that I am a useless, leaky pot, good for nothing and going nowhere. And the story of “Mr. Squishy” captures this feeling perfectly.

As much as it scares me, I also really like the story. It is redeeming to explore its maze of meaninglessness because it helps me navigate my life. It forces me to find a way out before its nightmare becomes my reality.

If I face my fear of futility now, I can avoid it.

But if I avoid my fear of futility, I will one day have to face it, and by then it will be too late.

Chocolate Trash and Those Who Manufacture It

The title of the story comes from the sponsor of the meeting. Mr. Squishy is a confectionery company (like Hostess) that makes ultra-glycemic snacks loaded with preservatives, the ones sold in gas stations and the checkout lanes of grocery stores. The story is set in 1995, when these products began to surge in popularity. And so, in the endless search for more profits, Mr. Squishy has organized this meeting to test consumers' opinions on their newest sweet treat.

Listen to Wallace's satirical description of the proposed product:

"Felonies!—a risky and multivalent trade name meant both to connote and to parody the modern health-conscious consumer’s sense of vice/indulgence/transgression/sin vis à vis the consumption of a high-calorie corporate snack....

Felonies! were all-chocolate, filling and icing and cake as well, and in fact all-real-or-fondant-chocolate instead of the usual hydrogenated cocoa and high-F corn syrup, Felonies! conceived thus less as a variant on rivals’ Zingers, Ding Dongs, Ho Hos, and Choco-Diles than as a radical upscaling and re-visioning of same."

This is the kind of twisted logic that a company like Mr. Squishy uses to design its new product. It's all marketing jargon that obscures the real truth—this is just a knockoff brownie. And yet they will go to great lengths to sell that junk to unsuspecting customers under the guise of something much better.

It's hard to say who is more deluded—the company or the consumer. Mr. Squishy is trying to convince the consumer (and themselves) that the consumer needs this product (right now) in order to be happier, healthier, wealthier, or whatever. But the consumer is willing to buy the lie.

To launch their advertising campaign for Felonies!, Mr. Squishy has turned to the marketing company Reesemeyer Shannon Belt Advertising (RSB). In turn, RSB has hired the consulting firm Team Delta Y to conduct research for the project, including organizing focus groups like this one to collect data on consumer's reactions to Felonies!

If this is starting to sound convoluted, good. That's the point. This entire new-product-development process is incredibly intricate, almost to the point of being obtuse—requiring the coordination of multiple departments within all three firms, complex statistical calculations, and high-powered computers on which to run those calculations. All this to determine whether Felonies! will be a hit or not, so they can pull the trigger on manufacturing and distribution and advertising and so on. It's a colossal corporate machine, a Rube-Goldberg device that only spits out sugary snacks that are of no real use to anyone, anywhere.

The layers of futility are piling up.

My first job was very much like this. I worked as an auditor for a big accounting firm. I visited our clients to check their books and make sure everything was kosher. Except that the clients were the one paying us, so it was in our best interest to say that everything looked good. Even when it didn't. When I expressed my concerns with this dilemma to my bosses, they told me I was too inexperienced to understand how things worked.

Moreover, the firm had already billed the client for a certain amount of hours every week: 60 for each employee, to be exact. So even when we pushed hard and got all our work done early, they told us to stay in our seats. To this day I can remember the agony I felt in the winter when dusk darkened the windows at 5:00pm, this a signal that I still had to stay at the office for five more hours, inventing work—work that ultimately didn't matter because we were going to give the client the green light anyways.

In short, I was a cog in a machine that produced nothing at all. And I was losing my life in the bargain.

Our Glorious Hero

The protagonist in “Mr. Squishy” is caught in the same trap. He is Terry Schmidt, 34 years old, chubby, pale, and socially awkward, "with a helmetish haircut and a smile that always looked pained no matter how real the cheer." He lives alone in a cookie-cutter apartment. He fills his free time watching satellite TV, collecting rare coins, and taking "power-walks on a treadmill in a line of eighteen identical treadmills on the mezzanine-level CardioDeck of a Bally Total Fitness."

The sole excitement in his life is his coworker, Darlene Lilly, not really all that attractive herself, but nevertheless Schmidt's only real prospect. To make matters worse, Darlene is married and thinks of him as only a friend. Schmidt has never had the guts to tell her how he really feels, though he fantasizes about her every night.

Schmidt is even more tragic because, despite his sad life, he has a good heart. All he ever wanted to do was "make a difference in the world." He began his career filled with ambition, which he thought made him special, but:

"In Terry Schmidt’s case a certain amount of introspection and psychotherapy ... had enabled him to understand that his professional fantasies were not in the main all that unique, that a large percentage of bright young men and women locate the impetus behind their career choice in the belief that they are fundamentally different from the common run of man, unique and in certain crucial ways superior...and that they can and will make a difference in their chosen field simply by the fact of their unique and central presence in it."

Who hasn't felt this way? I certainly did... and still do. It’s convicting to realize the similarity in our thoughts.

The fictional Terry Schmidt is a big loser, and I'd like to think I'm different. But sometimes I wonder if I really am... I often feel lonely, awkward, shy, and unsuccessful too.

Despite his current sad state of affairs, Schmidt has retained his high aspirations. Even after working hard to get to Team Delta Y, and spending eight years on the team, he’s still striving hard for a promotion that will finally give him a say in the direction of the company. And he daydreams about one day starting his own firm and making marketing history like all the stories he studied in school.

The Unraveling of His So-Called Life

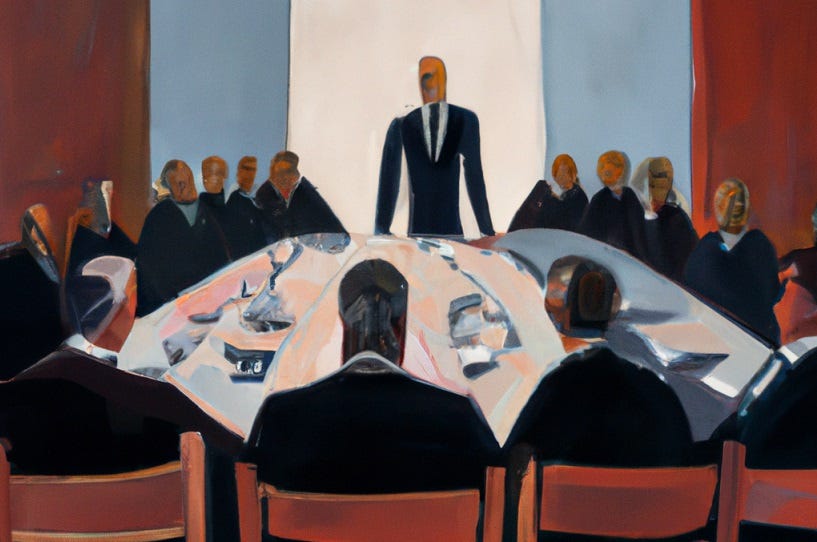

Today, Schmidt is leading the focus group in a nameless conference room on the nineteenth floor of a nondescript office building. His attention is elsewhere though, since he has given this exact same presentation over a thousand times.

This meeting is a little different, however, because a realization is dawning on Schmidt, though he tries to suppress it. He appears upbeat and unrehearsed during his little spiel to the 14 people they wrangled into the conference room. But his mind is churning in the background, fretting over a terrifying epiphany, as unavoidable as an unexpected earthquake.

The layers of futility are unraveling before his eyes, and each one is more awful than the last.

First, it dawns on Schmidt that this meeting is pointless. All the men here today have "faces arranged in the mildly sullen expressions of consumers who have never once questioned their entitlement to satisfaction or meaning [and who] had never been hungry a day in their lives."

They don't care about Felonies! They certainly don't care about Schmidt. They only care about themselves. They are growing frustrated at being kept in the meeting for so long and having to listen to Schmidt ramble on and on, and their sugar high is starting to crash. No one wants to be here and no one is contributing to the meeting, so the results will be pretty much unusable anyways.

Second, Schmidt is realizing that all these focus groups are a waste of time, because RSB (the marketing company) doesn't really care about the results. Whether consumers really like Felonies! or not doesn't matter, because their client Mr. Squishy has already spent so much money on the product-development-process that they can't afford to turn back now. So what everyone really wants is data that presents Felonies! in the best light possible, that prophesies their success. This way, they can justify such a large investment, even if it fails. They will just use Team Delta Y as a scapegoat for their failure.

And as any statistician knows, data can be creatively manipulated—sliced, diced, and rearranged—to present any results you want, whether they’re true or not.

Third, as Schmidt reflects on this, he is starting to feel a another layer of futility, this time of the marketing industry as a whole. He thinks to himself:

"no no all that ever changed [in marketing] were the jargon and mechanisms and gilt rococo with which everyone in the whole huge blind grinding mechanism conspired to convince each other that they could figure out how to give the paying customer what they could prove he could be persuaded to believe he wanted, without anybody once ever saying stop a second or pointing out the absurdity of calling what they were doing collecting information..."

I love that line in bold: the hypothetical customer doesn't even want the product, but marketers can persuade him—not to actually want the product, but—to believe that he wants the product. Or at least marketers try to convince each other that they have this power of persuasion.

It’s so convoluted and circular it makes your head ache.

Schmidt also realizes that even if a product does succeed, it might only be temporary. The market is driven by fads and trends, and those can change from month-to-month. In the long run, even a well-designed and well-marketed product may have zero impact, and ultimately be a waste of time and money.

And even if Felonies! were to succeed in the long run, consumers still lose. They’ve only been persuaded to spend their hard-earned money on trash, on a product that promises happiness and satiation but delivers nothing but detrimental health effects.

You Are Obsolete

Ok, that may all be true, but Schmidt still clings to the hope that one day he can rise to the top of this company, or start his own firm, and "make a difference." But is that still realistic?

Schmidt, still speaking on autopilot to the group, ponders this question, and the answers are not promising.

Because, if he's truly honest with himself, he has not had any measurable success in his career over the last decade. Younger, less qualified employees get promoted before him every year. He’s been stuck in his role (in this very conference room) for thousands of days of his life. He describes graphic, recurring nightmares of doing the exact same thing for the rest of eternity.

And Schmidt knows deep down that he will never get promoted, because he doesn't fit in. He's too nerdy and socially awkward. He's so bland and forgettable that people "whom Terry’d worked with for years have trouble recalling his name, and always greeted him with an exaggerated bonhomie designed to obscure this fact."

And even if he did get promoted...

"the only substantive difference would be that he would receive a larger share of Team Delta Y’s after-tax profits and so would be able to afford a nicer and better-appointed condominium to masturbate himself to sleep in and more of the props and surface pretenses of someone truly important but really he wouldn’t be important, he would make no more substantive difference in the larger scheme of things than he did now."

Realistically, he wouldn't have a say in the company, because everything is run behind the scenes (as we learn in the story), through nepotism. And despite more money, his personal life would still be stagnant. So what’s the point?

When I was a junior accountant, people told me that I should stick around just a bit longer and things would get better. That I'd get promoted and have more opportunities and more money to show for it. But as I looked up the corporate ladder at my boss, my boss's boss, and beyond, I saw only more misery. Every rung came with more responsibilities, more worries, less freedom, less peace. And still no actual say in the company, because invisible power-players made all the real decisions (sometimes really bad ones).

What good was all that money if I had no time to enjoy it? What good was a promotion if it didn’t grant me any additional autonomy? No, I had to get out.

But there is one final layer of futility in the story.

Schmidt will also be out of a job very soon, and then he will be completely useless. This is 1995, remember, and the internet revolution is about to change marketing forever. The practice of focus groups will be giving way to that of data analytics. Facilitators like Schmidt will be laid off in droves because it just doesn't make sense anymore to bring a group of consumers into a room, subject them to surveys and group discussions for an entire day, then try to make sense of the muddled results. Not when marketers can get more accurate data online, immediately, at a fraction of the cost.

Schmidt is already obsolete, he just doesn’t know it yet.

Now I Am Become Mr. Squishy, The Destroyer of Hope

And so the whole thing, from top to bottom, is simply futile. A leaking pot. Good for nothing.

Schmidt is starting to realize this, right here, right now, in the midst of his presentation. It’s becoming clear to him that he will never be able to make a difference, neither in his career nor in his personal life.

There just doesn't seem to be any way out, and no hope for anything to change. In fact, the only thing that does change is Schmidt’s body. He’s getting older and fatter each year, feeling more self-conscious about how he looks and the way he walks.

And in his lowest of lows, Schmidt identifies with the caricature of the Mr. Squishy logo2

[He] would look at his face and at the faint lines and pouches that seemed to grow a little more pronounced each quarter and would call himself, directly to his mirrored face, Mister Squishy, the name would come unbidden into his mind, and despite his attempts to ignore or resist it the large subsidiary’s name and logo had become the dark part of him’s latest taunt…

[It was] a design that someone might find some small selfish use for but could never love or hate or ever care to truly even know.

I believe Schmidt is in some sense responsible for his fate, and the final nail in the coffin is his acceptance of his situation. He gives in to the futility, and gives up on himself.

Conclusion

What haunts me about the story is its resemblance to my own life. It makes me ask myself questions like, "Am I any different than Schmidt? Is my life useful? Is it helpful to anyone? Is it ever going to change?”

I left the tedium of accounting long ago, but I still wrestle with my purpose in life. I still worry that my work on the ambulance and my writing are ultimately pointless. I still fear that my ambitions are disproportionately higher than my talent. And that all my efforts will come to naught.

Perhaps I will always wrestle with these fears, and that’s part of carving out a purpose.

Maybe it’s not the work itself that is meaningful, but the way I approach it. Perhaps when I give it my all, when I choose to be excellent, it becomes ipso facto meaningful, regardless of the results.

Most people are afraid of death, especially when it threatens to take them, at the end of their days, or when illness or injury strike. I have seen it in the eyes of some of my patients.

I'm not exactly afraid of death—I actually thrive on danger. What I fear is something much worse—being dead while still alive. I am afraid of leading a life that amounts to nothing, where I might as well have been dead. A life that ends with the final and angry shattering of a leaky clay pot that was of no use to anyone, ever.

This fear is terrible to behold, and yet I must do so. I have to face my fear of futility in order to overcome it. And stories like “Mr. Squishy” force me to do just that.

“Is my life useful? Is it helpful to anyone? Does it matter?”

No one can answer those questions but me. And the only way I can answer them is to get up every day and live my life to the fullest. I have to fight against weakness and selfishness and to strive after courage and love. I have to reject nihilism and embrace optimism.

I have to prove to myself every day that my life is not futile. It is this very act that makes it not so.

The alternative is to give up, and give in, and I refuse to do that. And maybe that’s what separates me from Terry Schmidt.

I am not Mr. Squishy. I am Melbourn Grant Shillings.

Please give me anonymous feedback here!

Footnotes

This essay is a heavily revised version of a previous essay, called Clay Pots.

Clay pots

Mr. Squishy is a short story by David Foster Wallace. On the surface, it is about the most pointless and boring meeting of all time. But at the end of all the tedious monologues and extensive descriptions and seemingly irrelevant tangents, it becomes clear that the story is instead about something much deeper—it's actually about futility.

The Mr. Squishy logo above is my attempt to use AI to generate the image based on Wallace’s description: “a course line-drawing [of] a plump and childlike cartoon face of indeterminate ethnicity with its eyes squeezed partly shut in an expression that somehow connoted delight, satiation, and rapacious desire all at the same time.”

I've had this waiting in my inbox for a while and I think I ended up reading it at the perfect time. My current game project is very related to this. Thank you for sharing this story!

i very much enjoyed this and the whole thread of it thrums like a taut and untuned banjo string like the tension I feel at 55 and not thinking i have any purpose in life other than making the dinner and sometimes making my partner's life a bit easier