It was my first real job. And even though it was a really good job, after only a year of working there, I quit. Honestly, I was just tired of the job.

I was lazy, and I'm proud of it.

Laziness is actually the most underrated virtue.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Allow me to explain what happened:

When I was 22, I graduated from college and I went to work for one of the Big 4 accounting firms—probably the best job I could have hoped for in my career path. At first, I worked really hard. And I was happy to. I was sprightly and full of energy, ready to apply everything I had learned in school, to prove my capability to my coworkers, to make proud the people who hired me.

But within a few months, the luster wore off, and I didn't like it very much anymore. Well, that's a bit of an understatement—I was miserable. I wrote about this in much more detail in another essay, but suffice it here that I felt like I was dying. 1

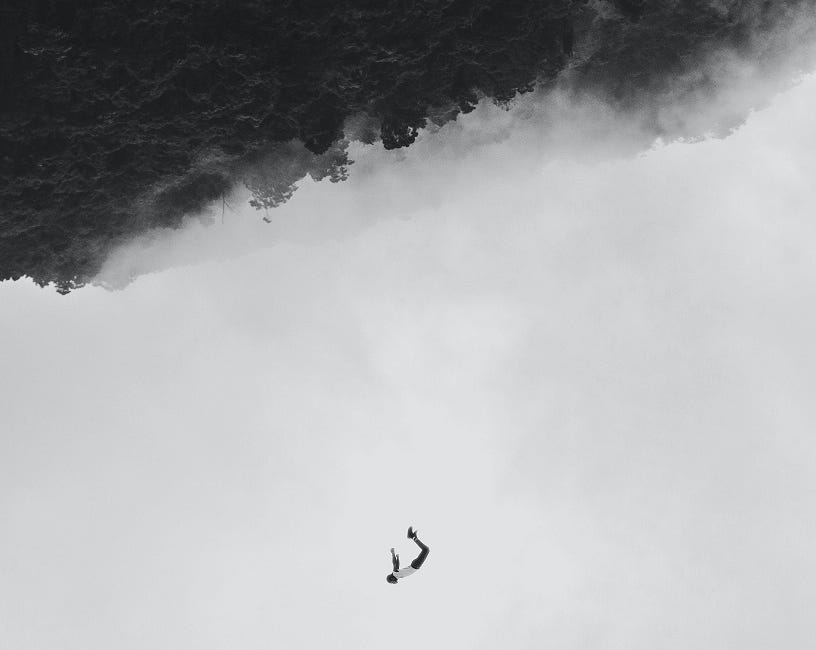

So I quit. Against the advice of nearly everyone, I gave my two weeks notice and walked away from it all. Well that's a bit of an understatement too. They said I was committing career suicide. I didn’t just walk away— it was more like I did a double backflip off a huge cliff.

Everyone thought that this whole ordeal was due to sheer laziness. "Don't you know that you have to pay your dues? You have to work hard for a long time before things get better..." But I didn't want to. Like a petulant child, I spit out my food.

Was it the wrong decision?

Hard to know for sure.

Because, in the short term, it seemed like I made the right choice. The job I found after that was better in every way. I moved from Houston, Texas to Palo Alto, California. Houston is known for being very hot, very concrete, very flat. Palo Alto is known for its year-round Elysian weather, its eclectic mix of techies and hippies. and its proximity to stunning mountains and towering Redwood trees and the sparkling Pacific ocean (and dozens of national parks).

And that was just the setting—the actual job was even more idyllic. My first job was working at a generic professional-services company, going to the offices of our clients, working out of closets where they set up temporary desks for us. The second job, I got to work at my dream company, EA Sports.2 I had my own desk, with three walls that gave me privacy, and a window view of a grassy lawn. Instead of working 55 hours a week, I worked 35, and I got a 15% pay bump too, with the potential to make even more as I advanced.

You see, even in that first year, I learned something invaluable:

Laziness pays.

I didn't like the status quo. So instead of accepting it, or "settling," I decided to change it. I sought out the unknown. Greener pastures. It was a gamble, and it might not have worked out.

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable persists in adapting the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” —George Bernard Shaw

The risk, of course, was that I might have forfeited an amazing opportunity, and never have been able to recover. Or maybe it wasn't a problem with the job itself, but with me—unwilling to put in the hard work. Maybe I would just start a chain reaction of quitting, job after job, and end up a bum.

What actually happened? Keep reading to find out…

Hail the hard worker

But why does it feel so foolish to praise laziness? It feels like taboo, even blasphemy.

It's because it's no exaggeration to say that we worship the hard worker. And that's especially true in American culture. We adulate the one who arrives early and lingers late; the one who sacrifices his evenings, and his weekends, and his vacation time, to work; the one who is "burning the candle at both ends." There's a legend that Elon Musk used to bring a sleeping bag to work in his early days as CEO of Tesla, so he could sleep at work. And we admire that.

But why do we do this?

We worship hard work because we have nothing else to measure.

For most of our history, our performance at work was judged by the fruits of our labors. And I mean literally, fruits. When we were hunter-gatherers, a successful day at "the office" meant bringing back some nuts, or berries, or mushrooms, or tubers. And a really great day (something worth celebrating with a festival3), like the equivalent of closing a big deal or delivering a killer presentation, meant returning to camp with a slain deer, or boar, or some other source of meat. So it was very obvious whether you did a good job or not: your hands were either full or food, or they weren’t.

And even after we developed agriculture and husbandry, our productivity was easy to measure, if less frequent. A good year meant a good crop. The proof is right there for everyone to see— is there food on the table, or not? Are the grainhouses full, or empty? Is the herd looking fat, or lean?

And if you weren't a farmer, then you made pots, or wove baskets, or cobbled shoes, or smelted swords. When you were done with your work, you could put it on display for everyone to see. And not just see, but actively use. If the pot shatters, you did a shit job. It the shoe doesn't fit—well, you get the point.

But how is it now? It is almost impossible to tell whether we did good job or not. Most of us don't make products anymore, we perform services. We analyze, we consult, we design, we sell, we account, we supervise, we program, we teach, we treat. These jobs pay more precisely because their value is so intangible, so difficult to quantify. Our modern jobs are anything but a commodity.

But herein lies the problem: at the end of the month, did we do a good job? Did we build something meaningful? Were we productive?

Hard to know for sure.

We can look at the metrics of the business:

Did revenue go up?

Did costs go down?

Did we finish faster?

Did we satisfy our customers?

But how much of this is within our control?

Was it just a bull (or bear) market?

Was it someone else at the company, and not us?

Was it simply the magic sauce that our company has?

Was it blind luck?

Since we have nothing obvious and specific to point to, we point to our busyness. It's impossible to tell whether we did a good job or not, but—hey—at least we put a lot of effort into it. Right?

Actually, that's not clear either, because, in my experience, if you work more than 40 hours a week, you are actually so tired that you aren't really working very hard, at least not the entire time. You're not thinking sharply. You’re not as creative. And then the parts of your life outside work start to suffer. And then that makes your work start to suffer, in a vicious cycle. It's just impossible to sustain 50 hours of high-quality work, week after week after week. You might be able to pull yourself together and white-knuclke it and do it one or two weeks in a row, but not more than that. You’ll just burn out.

So then now, finally, we are pushed to our last stronghold—at least we spent a lot of time at work! At least we were busy!

That’s good enough, right? Right?!

Work Smarter

When Tim Ferris was 22, he did things very differently than me. His first job was working in sales, making cold calls all day. Most of his colleagues worked the regular hours of 9am-5pm. And the goal was to try to reach a manager, or some other executive who had decision-making power. The irony though, is that those same people are also very busy from 9am-5pm, and don't have time for cold calls. They are putting out fires and answering questions from subordinates.

Instead, what Tim did was get to work an hour early, and stay an hour late. He would make all his calls from 8-9am and from 5-6pm. The rest of the day he would just relax, go for a walk, read a book, play hackysack, whatever... But during the windows of time that he did work—before the managers got too busy, and after all the rest of their employees went home—Tim had a much higher likelihood of reaching his targets on the phone. And as a result, he had a significantly greater success rate than any of his peers. So he worked two hours instead of eight, and had 10 times as many sales. So his success rate per hour was through the roof: over 40 times more than his colleagues.

The point—work smarter, not harder. Tim's laziness is what inspired him to try to find more efficient ways of doing things. He knew that the status quo was bunk, so he smashed the system and rebuilt it from first principles. And as we know, that never stopped, and so now he's a multi-time bestselling author, top podcaster, angel investor, and so on.

Yet we still blindly worship the employee who works long hours. Employers now expect their employees to work smarter AND harder. “You should be able to work smart all day long, every day.” But that's not how it works. To be at your best, you can only do it for a little while. And then you have to spend a lot of time to rest and recover. It's like a sprint, rather than a marathon…

But that's also the wrong analogy. We think work is like the tortoise and the hare— slow and steady wins the race. But modern productivity is not a race; it's not even linear, nor is progress easily measured.

Instead, it's more like crossing a river: the hard worker would stop complaining and just get it over with, and begin the journey of walking all the way around, ‘til he finds a crossing, which would take a whole day. Instead, the lazy guy just finds a dead tree trunk and rolls that across the gap to serve as bridge. A lot more work, in the beginning, rolling trees, but he saves himself hours by being able to cross here and now.

This is leverage through laziness. This is innovation born of indolence. With 25% the of the input, you get 1000% of the output. That's what Tim did.

Humans have always been lazy

But Tim is not the only person to utilize his laziness to build bridges. In fact, we've been doing it for all recorded history. Perhaps the most defining quality of humans is laziness.

When we got tired of sitting in the cold and dark, we found fire. When most mammals were eating grass and leaves (think cows, giraffes, elephants, gorillas), we found much denser sources of nutrition in nuts, berries, mushrooms. When we got tired of foraging, we found a way to use fire to cook meat. When we got tired of hunting that meat, we started shepherding.

There was a time when walking was too tiring, so we tamed horses. And then there was a time that riding horses was too much work to keep them fed, and shoed, and groomed, so we built bicycles. And then there was a time when pedalling bicycles was too much work, and too slow, so we built automobiles. And then planes. And maybe in the future we won't travel at all, and just use VR.4

Conclusion

Of course, there is a kind of laziness that is purely self-indulgent, and gets us nowhere. That’s what we typically think of when we use the word. But it is by no means the only kind.

There is also a kind of laziness which seems like hard work, but is actually based in fear—or worse—complacency. If I had stayed at my first job, I could have congratulated myself that I was being industrious and disciplined. But the truth is, I would have just been being too much of a wimp to demand more for my labor, for my abilities, for my ambition. I would have just been settling for the status quo. Sometimes, that’s necessary. But in my case, it wasn’t.

It’s one thing to have a vision for the future and wait for it. It’s another to avoid the present. It’s not vision. It is instead willful blindness. It’s the worst sort of lie. It’s subtle. Willful blindness is the refusal to know something that could be known. It’s refusal to admit that the knocking sound means someone at the door.

—Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life

Ultimately, I did end up starting a chain reaction of quitting. I only worked at EA Games for three years before I quit again. And I started and quit several more jobs over the years following. But now I’m in a totally different situation, working as an EMT. My job is physically and emotionally much more demanding. It’s much more stressful, and the hours are longer. But I’m enjoying it.

I feel like Peter from Office Space, who quit his high-paying but soul-killing job as a programmer, only to end up as a construction worker. But he loved his new job.

I’m also working hard on building The Apocalypse. This week marks 22 weeks in a row! It takes a massive amount of effort to finish these essays each week, on top of my job and all the other things I want to do. But I’m enjoying it.

And lastly, as I wrote about a few weeks ago, I also spend a ton of time and effort exercising.5 This past Sunday, I spent an hour taking a kickboxing class, and then immediately after that another hour doing Jiu Jitsu (both sports I’ve only found in the last few years after trying many others). I was so exhausted afterwards that I’ve barely been able to move for the last two days. But I absolutely love it.

The point—what looks like laziness to a lot of other people may just be you trying to find something that is much more suited to you. It may be you trying to bend the world to your desires, rather than you bending your desires to the world. And if you’re lucky, you might just invent the next big thing.

When we do find that work (or activity) that suits us, we are happy to throw ourselves into it. But finding that work in the first place may look like laziness. Don’t worry about it.

So I’ll leave you with a question, paraphrased from James Clear:

What looks like work to others, but feels like play to you?

Footnotes and links

I wrote about how miserable I was at my first job in this essay:

Two kinds of dying

I almost died yesterday. It was awesome. I know this sounds crazy, and maybe it is, but the episode yesterday validated an idea that I've come to realize over the past few years— sometimes, the closer we are to death, the more we feel alive. But there's a specific way in which this feeling comes over us. It’s not always such a positive experience. Someti…

“It’s in the game.”

I wrote about the prehistoric party in this essay:

The Comfort of Clamor

It is civil twilight, that ethereal hour just after the sun has dipped below the horizon, but has yet to relinquish its grasp upon the earth. Above, the sunset is a backdrop of quiet serenity, exquisite beauty, and stately nobility, which contrasts sharply with the chaotic energy now bubbling below, a witches' cauldron of noise and activity, here on Bou…

I wrote about the potential for VR to eliminate travel in this essay:

Stay in your homes

When Virtual Reality becomes mainstream, we will no longer travel. VR presents the opportunity for us to enjoy an unlimited buffet of all kinds of fantastic experiences, all from the comfort of our couches. These experiences can be grounded in reality (such as visiting foreign countries, or meeting with friends in virtual chat rooms), or they can be surr…

I wrote about my dedication to exercise in this essay:

I am Interminable

We stumble back into the apartment at 1:30am—both of us sober—but simply sapped of all our energy. Most of the night was blur, but what he does next is a freeze frame, etched into my memory. At this time of the night (or morning?), we are husks. The soles of our feet have now petrified into planks of wood from standing on them for so many hours, our thr…

Another insightful piece. This isn’t related to your main message – but your point about us worshipping hard work because we have nothing else to measure, really got me thinking. It’s so true that our society values hard work as our primary measure of ‘success’ and ‘achievement’ in life, and doesn't really think outside of that. I recently had a family member post on LinkedIn about how marriage to their spouse was the greatest achievement of their life (when LinkedIn is often used for career announcements). This person received feedback from an individual who was alarmed that he could view this as his greatest achievement when he’s accomplished so many other things – the degrees, jobs, etc. But to him, it was his greatest achievement because it was the thing that brought the greatest amount of love and understanding into his life. I think it’s sad that society has a tendency to measure success by our pay and careers, rather than the actual impact that we make on others and ourselves. I think our success should be measured by the strength of our connections with those around us. The amount of love, gratitude, patience, respect that we exhibit.

I think this whole essay can also apply to relationships. I think we can be really lazy in relationships that we’re not that into – I dated a guy who would take over a week to respond to any message, and told me that he just wasn’t good at communication. The truth is, he was lazy about engaging with me because he didn’t really want to be in the relationship. I’ve also found myself acting in similar ways when I wasn’t interested in the person. But on the other end of the spectrum – I’ve been willing to go above and beyond, do anything in my power, to be there for those I love – it doesn’t feel like a chore, it feels like a blessing, because I truly love these people and I want them to know it (and I've had others do the same for me).

In some ways, I also think the ‘in praise of laziness’ can apply here in terms of calling friends – I have a friend who doesn’t often want to take the time to speak at length, but she will always answer her phone and give you a quick ‘I can’t talk now, but it’s great to hear your voice, I hope you’re doing well and I think about you all the time’. Whereas I have other friends (I’m often guilty of this), who won’t pick up their phone until they find themselves in a 2-hr block and with the energy required for that long-overdue phone call. It’s pretty clear who I actually end up speaking to more often and feeling most connected to – the friend who uses a lazy approach that works.

Excellent essay! I believe when you find the work God has called you to and gifted you with what you need to do that job, it is actually enjoyable. Sure not every hour of every day but overall and the “success” lies in your contentment.