Just get it over with

Or linger as long as possible

I'm walking between the tops of two skyscrapers, hundreds of floors above the ground level, on a bridge composed of nothing but a cable that is as wide as my wrist. The wind hits me in small gusts, making me wobble back and forth as I try to retain my balance. The gap is about the length of a football field, and it will take me about an hour to cross it, very slowly, very deliberately. I can feel the eyeballs of hundreds of spectators drilling into my body; I can feel their admiration, their criticism, their expectations, their optimism, their derision. Time feels as though it has stopped, and I have no room in my head to consider any of these thoughts—they just fly by like the birds that soar among me at these heights.

Or at least, that's what it feels like as I try to paint.

You see, painting is like tightrope walking—if you make one mistake, you fall into the chasm, and all is lost.1

Ok, so perhaps the stakes are not exactly the same between the two disciplines. With tightrope-walking, when I say "all is lost," I literally mean all. You fall, you die. No respawns. No more tightropes for you. No more walking for you, either.

With painting, in the worst case scenario, you lose your current project. And also all the time and effort (and materials) you invested into it. Maybe you can't make rent that month and you get kicked to the street. But you'll still live.2

Nevertheless, we must admit that in both cases, we are dealing with a very precarious situation, in which disaster is always near at hand, and so we must act delicately.

There is a kind of breathless anxiety surrounding the entire enterprise, an overpressurized atmosphere, electrically charged, and an uneasy tension, all of which demands complete focus. At any point, it could all spiral out of control and into nothingness.

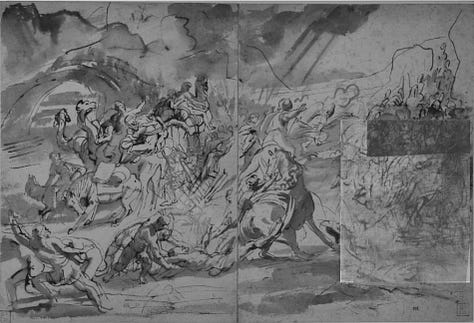

In the above gallery are several iterations of the legendary painting, The Conversion of Saint Paul by Peter Paul Rubens, completed over the course of two years from 1610-1612. Each one is vastly different from the others, and you can see how at any point in time, the painting’s path could have diverged into something completely unrecognizable from what we have today. Perhaps it would have never become a masterpiece. Perhaps it might never have even been finished (as has been the cast with many great works of art).

And this is why, whether in painting or tight-rope walking, it would seem to us that it would be a huge relief for the performer to be finished with the whole endeavor. To “just get it over with.”

Right?

Dragging your heels

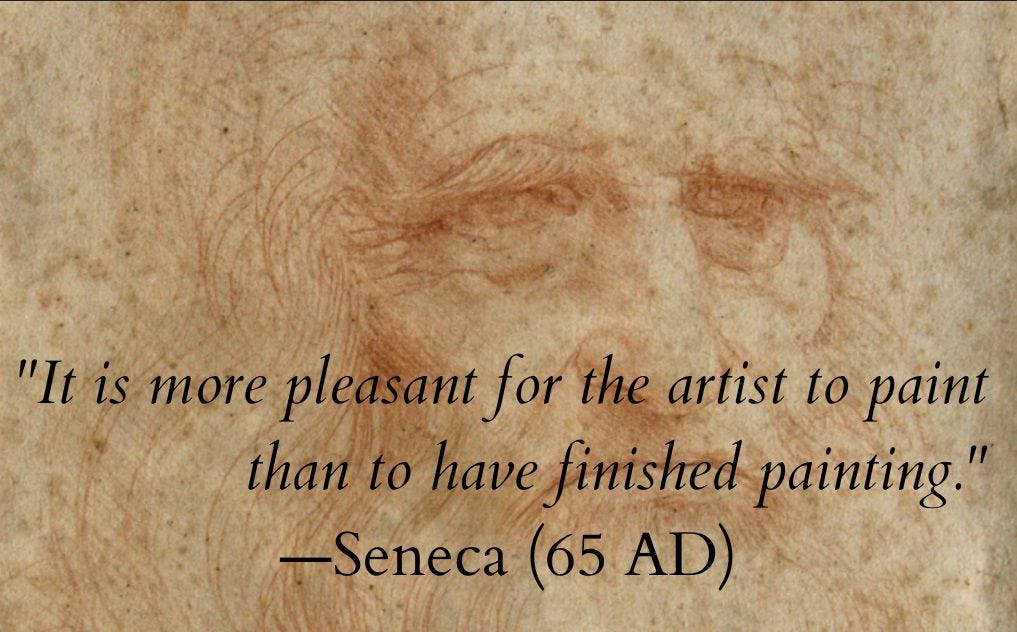

But so, when I came across this quote from nearly 2000 years ago, I was struck dumb:

But how can that be so?

Wouldn't the artist rather have completed the painting? For as we have already said, the entire project is fraught with the ever-present danger of potential mistakes. And moreover, there is the constant fear that the artist will be unable to create something worthwhile, something novel, something beautiful, something meaningful. It's like being pregnant, but not knowing if you will be able to deliver on time—or at all. We’d rather the baby be born already. And not to mention, (great) paintings often take weeks or months or years, and the aforementioned focus must necessarily fatigue the artist over time...

So wouldn't the artist rather be done with it all already? To have the painting completed, with his signature scribbled in the corner. To have the painting framed so that he can celebrate his achievement, and to demonstrate it to his friends, much to their acclaim (or to his enemies, to their spite). Or best of all, wouldn't the artist rather sell the finished work to his agent, or a collector, or even a museum(!), and then use the money so that he can get on with the rest of his life?

No.

What's shocking is that Seneca says the complete opposite: the artist would rather be painting, miles up in the air, balancing delicately on the tightrope of creation, dealing with all that uncertainty and stress and fatigue. But why? Why, why, why?

Because a true painter loves to paint.

A painter is only a painter when he is painting. Otherwise, he is just resting. The same is true of an athlete, or a teacher, or a doctor. The job is in the doing.

As I said two weeks ago,3 the worst possible curse is to realize that you are “a writer who doesn’t write.” I’ve been there before, and it’s awful. How can you call yourself an athlete if you don’t play, a teacher if you don’t instruct, a doctor if you don’t heal?

To be done painting is a just a small part of the job, a necessary evil, required in order to continue the act of painting. It is the exhale that allows us to inhale again.

Seneca continues:

"When one is busy and absorbed in one’s work, the very absorption affords great delight; but when one has withdrawn one’s hand from the completed masterpiece, the pleasure is not so keen."

What he's talking about here is an ancient understanding of Flow—when all the conditions are just right (optimal level of difficulty, clear and immediate feedback, known objectives both micro and macro, and a sense of control), then we are immersed in "peak human experience"—a state of where we realize powerful productivity, forget our sense of time, and know enjoyment, satisfaction, and bliss. Flow is when we are at our absolute best. The brain is firing on all cylinders, the body moving in perfect harmony, a gapless extension of the mind, an ecstatic dance, a self-perpetuating wave. Despite all the stressors of the tightrope/painting scenario, it's worth it in order to step inside this rocket ship we call Flow.4

Telic vs. Kinetic

But Seneca's observation is more than just a description of Flow; what he is really discussing is the difference between doing and being done.

This is a crucial distinction to make, as it actually underlies our approach to everything we do in life.

If we don’t recognize this, we will spend our lives completely wasting our time, chasing after the wrong things. But if we can understand this dichotomy, and apply it to our lives, then we can guarantee our satisfaction, no matter how difficult our circumstances.

Allow me to explain. For example, for most things in life, I just want them to be done. I don't actually want to do them.

I don't want to clean the house, I just want the house to be clean.

I don't want to go to sleep early tonight, I just want to feel rested tomorrow.

I don't want practice meditation and sit still and do nothing for 15 minutes every day, I just want to be zenlike and peaceful and serene.

I don't want to practice guitar for 60 minutes every day, making the strings buzz by missing them, hitting the wrong notes, building up calluses on my fingertips, rehearsing the same songs over and over and over, I just want to be able to play Freebird flawlessly.

I don't want to grind away at a difficult job for 10 hours every day, slowly growing my career, dealing with bullshit and boredom and banality, I just want to be rich and powerful and famous. I want all the rewards and none of the trials.

These are all things in which the focus is on being done. And the doing is simply something we have to suffer through to get there.

So Seneca's observation begs the question:

Are you actually enjoying what you are doing?

An example: my friend Andrew likes to lift weights at the gym. He is good at it, and it provides him with a great way to exercise. But he told me the other day that he "needs" to start running more. Because he wants to be slimmer, and he thinks that's what girls like. So he told me about how he has been forcing himself to run instead of lift weights.

"Ok," I said, "but do you actually like running?"

"No," he said, "I hate it."

"So let me get this straight," I said, "you're going to spend several hours a week doing something you don't enjoy, instead of lifting weights, which you do enjoy, all so that when you take your shirt off maybe once a week, and only during the summer, hopefully some (single) girls will be around and might prefer your ‘slimmer’ appearance?"

"Hmmmm…."

It seems like a steep sacrifice for a questionable reward.

Andrew could spend more time running, but he wouldn't enjoy it. And as a result, he probably wouldn't run often enough to truly become a runner. And that's ok, because he has an alternative that is, honestly, a fine substitute. With weight-lifting, he can still achieve a similar end goal—that is, fitness.

Conclusion

Now we can't enjoy everything we do in life. There are some things, like paying taxes, or cleaning the house, which we have to do. These we want to “just get it over with.” On the other hand, there are some things which are pure enjoyment to do, but we really ought to limit (video games, netflix, junk food, and instagram all come to mind).

One last example: audiobooks. When I listen to nonfiction, I tend to listen at a speed of 2x up to 3x, depending. But when I listen to fiction, I listen at a speed of 1.0x or even 0.9x. Why? Because with nonfiction, I’m just trying to be done: to have acquired the knowledge within the book. But with fiction, the goal is to stay within the world as long as I can. I want to linger as long as possible in Middle Earth, or aboard the Pequod, or in the halls of Enfield Tennis Academy.

The trick is to find things that are enjoyable to both do and be done with. Our painter, just like our tightrope-walker would certainly satisfy this test.

To focus too much on the being done is to be miserable, and to focus too much on the doing is to wander endlessly and get nowhere.

We want to find activities that are so effective at inducing Flow, that we want to linger in them as long as possible. We don’t want to “just get it over with,” but rather we don’t want it to end.

If you find yourself saying “just five more minutes!” then you’re probably on the right track. Just make sure that there is an end result that is somehow meaningful or productive. Because believe me, I’ve said that probably a thousand times while playing video games. And not to bash on them too much, because I love them, and sometimes it’s ok to do those kinds of activities. Just not all the time.

As I’ve written previously,5 two of my activities that satisfy this test are writing and exercise.

What are yours?

Footnotes:

It also feels like this when I try to write, but I think, as you’ll see by the quote that drives this essay, painting is an example that makes more sense, and is probably more relatable for most people, as we’ve all tried to paint at some point.

But to be honest, I absolutely love this quote below from David Foster Wallace. It’s so profound that I still haven’t wrapped my head around it, which is why I’ve just left it (somewhat) hidden here in the footnotes:

“Writing-wise, fiction is scarier, but nonfiction is harder—because nonfiction’s based in reality, and today’s felt reality is overwhelmingly, circuit-blowingly huge and complex. Whereas fiction comes out of nothing. Actually, so wait: the truth is that both genres are scary; both feel like they’re executed on tightropes, over abysses—it’s the abysses that are different. Fiction’s abyss is silence, nada. Whereas nonfiction’s abyss is Total Noise, the seething static of every particular thing and experience, and one’s total freedom of infinite choice about what to choose to attend to and represent and connect, and how, and why, & c.”

And further, I will grant you that most painters have techniques and tools that allow them to edit mistakes in order to mitigate their *disastrousness*; or, better yet, they can act in a way to prevent irreversible errors in the first place. For example, painting a new layer over the mistake, or avoiding using the color black with a thick and large brush late in the process. And likewise, most tightrope walkers use a harness, so that a fall is simply a chance to rest and reset, instead of an Icarian plunge to doom.

I wrote about how painful it is to be a writer who doesn’t write.

I wrote about how I get to experience Flow each week with my essays due to the pressure of deadlines.

I wrote about writing and exercise and how I can’t stop doing them.

Love this essay - it really helped me at a time that I was feeling stagnant with my work/career (which was really recently, just a few weeks ago). I do feel like I've found a job and a path that really does bring me a sense of meaning and impact and joy. But lately I had gotten into the habit of focusing way too much on the 'doing', without a clear goal I was working towards. I was 'wandering endlessly' - and I wouldn't say that it 'got me nowhere' - but you definitely don't get near as far as you could, or you don't really even know where you get to, without a deliberate intention of where you want to go. I was letting life and work happen without taking charge of my path. And agree that it's great to find 'flow states' and I find them all the time - but the super important part that resonated with me from this is the knowing what 'done' means and defining this clearly. In the short term at least, I'm starting to set goals and targets to strive for, that I can review progress towards, and change course if I meet them or decide my priorities have shifted.

This felt so related to what I'm thinking about right now as well. For me that thing is to draw in sketchbooks, I love to just disappear into them in the moment, fill up pages and to look back through old ones. Maybe turning those ideas into products/things is just a way for me to make enough money so I can keep filling the sketchbooks.