Rock vs. Paper

Which would you rather write on?

At the climax of his career, he walked away from it all.

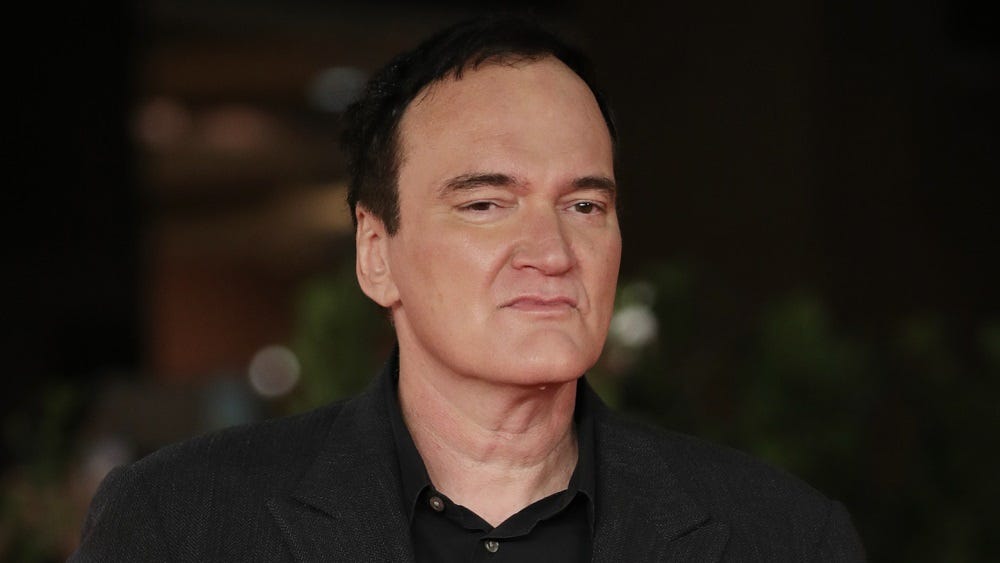

He was one of the most successful film directors of all time. Even among the celebrities of Hollywood, he was a celebrity. He had entered the world of cinema with a bang, and he never stopped popping off, just making more bangers, year after year. His style was distinctive, instantly recognizable, edgy and aggressive, and yet mainstream, beloved by many, discussed and analyzed and debated over.

Then, suddenly, he quit. At a time when his skills only seemed to grow sharper, his connections couldn't get any better, he had the adoration of millions of fans, when he could make whatever he wanted, he gave it all up. Just simply set the camera down and strolled off into the sunset.

Above; the iconic final frame from The Searchers

When he announced his early retirement, the world was stunned. In interviews, renowned show hosts literally begged him to stick around—just a little bit longer, please, make one more film, just one. Hundreds of producers offered to bankroll his next project, no matter what the theme, the demands, the budget; they believed in his talent that much. Actors—the best of the best—said they would act for free in his next project, if he would just do one more.

He listened to none of them.

But what's most shocking about his decision to leave is how recklessly wasteful it seemed—at least to all the millions of other Hollywood hopefuls who would have gladly given their left eye just to get IN to the movie business. And would have given infinitely more to be considered, like him, one of the greatest of all time. They say that in Los Angeles, 99% of those who call themselves "actors" are actually waiters and waitresses. It is brutally difficult to make it into the movie industry. It takes years and years of effort to get a gig, and most of those never turn into more gigs. Even if an aspiring actor does actually make a career out of acting, few make the A list, and those that do spend only a brief period of time there. The same is true of every other job in the movie industry, but most of all, directors.1 Literally everyone wants to be a director, to be the pilot of the ship, the quarterback, the head honcho.

This director’s trajectory was anything but conventional. He never went to film school. He worked at a movie rental store for years. And then, boom! out of nowhere, one of his scripts was picked up and his first film was funded, and it became an overnight success, and has remained a classic ever since. And it didn’t stop there; the hits just kept coming, each one better than the last. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom.

And then, one day, they stopped coming. It was not from any cognitive deterioration on the part of the aging director; there were no money or legal issues, no scandals in his personal life, certainly no lack of opportunities. No, he just decided that he was done. Finished. Despite the fervent attempts of everyone to sway him, he was convicted; he knew what he wanted to do.

But why did he do it?

He wanted to leave a legacy that would stand the test of time. He knew that like all directors—all artists for that matter—his work would eventually face a decline. It was only natural. He had risen to prominence from complete obscurity, his talent had blossomed and been celebrated, but then, at some point, he would inevitably slip into decay, his skills would diminish, and his output would suffer. In fact, we all face this trajectory—our lives mimic the typical pattern of any story, any population, any trend—first the slow start, then the rising action, the climax, the falling action and gradual decline, and, finally, The End.

What the director was trying to avoid was this natural decline in quality, producing a stigma attached to his later movies which must necessarily affect the perception of his earlier movies. So far, his entire portfolio had been hits. His batting average was 1.000. Why would he risk diluting that perfection? He didn't need the money.

No, the worst thing that could happen is that he would fail to recognize when his ability was waning, and the quality of his movies was eroding, and all the yesmen around him would never tell him what he really needed to hear—he was over the hill. Like Lucas, like Hitchcock, like Spielberg, like Scorcese, each of them had fallen into the trap of making bad movies after a string of successes.

No, he would avoid this fate. It would be simple: ten movies, ten hits.

Who have we been talking about?

We're talking, of course, about Quentin Tarantino.

But while his plan of checking out early may seem like the perfect solution, there's one serious downside: what if he hadn't reached his full potential yet? What if his peak was just up ahead? What if he was still just one more movie away from completing his masterpiece?

We will never know.

That's the tradeoff he decided to make. He chose to sacrifice possible perfection that may (or may not) have materialized in a single work of art, in order to guarantee perfection that was evidenced in a completed body of work.2

Carved in Stone

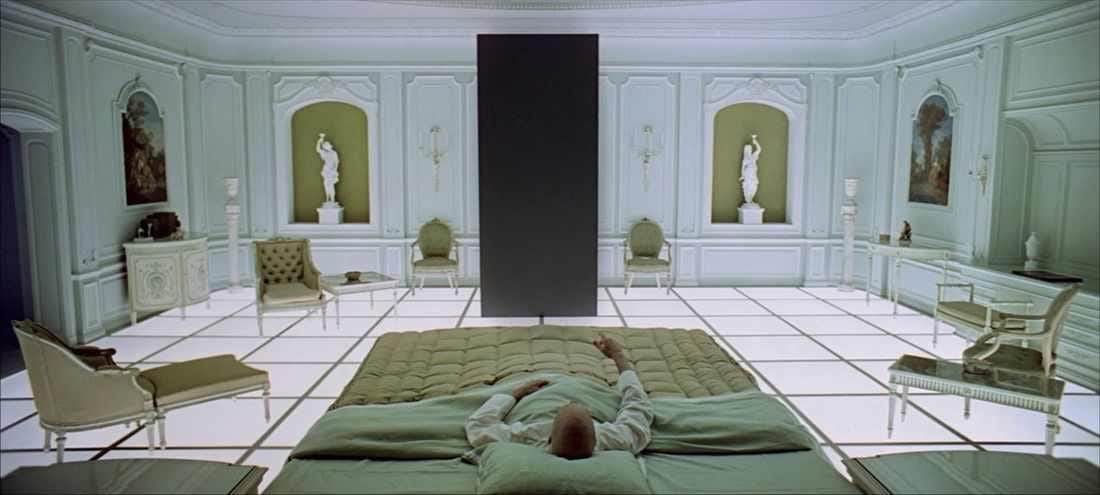

But Tarantino's fixation on his legacy is especially significant because of his particular artistic medium—within the realm of art, movies are the equivalent of stone tablets. Movies are massive undertakings, typically requiring financing in the millions of dollars (for a blockbuster), with production timelines of 1-2 years. They are not just the work of one artist (or auteur), but rather the collaboration of hundreds of individuals and multiple agencies (often different governments too). There's a reason the credits at the end of a movie tend to take five to ten minutes to unroll. There is the director, of course, but then there the screenwriters, the producers, the actors, the photography team, the makeup, the wardrobe, the location scouts, the set designers, the caterers, the accountants...

And those are just the “main” jobs—there are hundreds of others you haven't even heard of. One of the readers of The Apocalypse, Molly Berg, works in Hollywood on the production team for the Avatar series of movies.3 She is in charge of “Wound Continuity” throughout the series. What does that even mean? I wish I could say. I could guess, but I don’t want to do her an injustice. Of course, she also has a variety of other responsibilities on set, but that’s beside the point. What I’m trying to say is that a movie requires the coordination of an entire league of specialists, each of them experts in their own individual domain.

Contrast a movie with, say, a painting. A painting is a challenging project; it may take over a month to complete, plus hundreds of dollars in supplies: canvas, brushes, paint, soiled clothing, etc. Certainly more expensive than any of us might be wiling to spend on a whim, but also not nearly as costly as a film. A painting can usually be created by a single artist. And it can be edited later, if so desired; painted over. It’s less of a permanent fixture than a movie.

Above: My artist friends Will Day and Piki Mendizabal 4

Perhaps a book is somewhere in between a movie and a painting. It is generally the work of at least two people: the author and the editor. There may be a few others, such as a copywriter, a typesetter, etc. A good book may take about a year to complete, and cost in the thousands of dollars to do so. This is daunting, but helpfully so, because it forces the artist to really do a good job if he wants to complete such an endeavor. An author must clearly organize his thoughts into sentences, and paragraphs, and chapters, and all of these are reviewed dozens of times by the editing team.

“That’s pretty much all writers do: take the blooming multiplicity of the world and our experience of it, literally concentrate it down to manageable proportions, and then force it through the eye of a grammatical needle one word at a time.” —Michael Pollan, Caffeine

There are certain barriers to entry inherent to the publication of a book that ensure at least some level of quality. It is closer in permanence to a movie, and further from capriciousness than a painting. Still, I will readily admit that there are thousands of trash books published each year. Those barriers are not foolproof.

Finally, contrast each of these media—movies, paintings, and books—with much of the creative output that is available to us today, in 2023. Publications like this, The Apocalypse, are the work of one person.5 Here, a new essay is created every week—52 in a year. Then, of course, there are so many more publications: other authors on Substack, those on Medium, and those that work for major news outlets; The Times, The Journal, The Post. And minor ones too.

And let us not forget about all the tweets, the youtube videos, the facebook posts, the reddit threads, the instagram rolls, the snapchat stories, the tiktoks.

Above: yes, if you’re paying attention, you may have noticed that some of the icons are repeated, but that only proves my point about the redundancy of this information

All of this creative output that is produced on a daily basis is like an ocean of information, a tumultuous tide that incessantly crashes wave after wave upon our consciousness, the sea levels only rising as the ice caps melt and more and more people are born into the world, grow up, come online, and start contributing.

It never stops.

If producing a movie is like carving a stone tablet (à la the Rosetta Stone) then composing a tweet is like writing propaganda on a paper slip, to be airdropped into enemy-occupied territory. On one hand you have perhaps the most valuable piece of literature known to history, the only link to the deciphering of a previously incomprehensible language, and thereby the revelation of a rich culture.6 On the other hand you have scraps of paper not worth the kindling, mere confetti, brief vapors of thought that are here today, gone tomorrow.

The solution, obviously, is to pursue quality over quantity. To seek those sources of information and knowledge and wisdom and beauty that are timeless, transcendent, extra-ordinary. And once we find them, to dwell among them, drinking deeply from them, like fountains of life, instead of rapidly flitting from puddle to dirty puddle, taking a sip here and there, ever drinking but ever thirsty.

Jesus said to her, “Everyone who drinks this water will be thirsty again. But whoever drinks the water I give him will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give him will become in him a fount of water springing up to eternal life.” John 4:13-14

For example, rather than watching a couple of hours of Tiktok or cable TV, choosing instead to watch a Tarantino movie. Instead of reading Musk’s latest tweets, choosing instead to read Plato’s dialogues. The latter media endure, the former expire.

Next Gen

But herein lies a dilemma: When Tarantino is finished, who will replace him?

Surely, there must be an inheritor of the director’s chair. The role cannot end with him. The history of every artistic profession (as well as business, science, and every other endeavor) is necessarily composed of both preceding generations and succeeding generations. All of these fields must progress; they cannot remain static.

So whoever is next, how will they break into the mainstream? How will they transition from unknown nobody to up-and-coming hotshot to celebrated success story? They will likely have to follow the path of every other artist before—start small, start scrappy. Make mistakes. Fail fast. And then gradually get better, get more attention, get more respect.

But if we have already decided that it's a better use of our (extremely) limited time to focus on the best works of art and the richest sources of information and to ignore the constant crap, how will this new director ever get people's attention?

And this is exactly my problem. As an aspiring writer, I want to contribute to those fountains of life. I want write words that people quote to one another. I want readers to unconsciously nod their head as they follow along with a cogent argument, or laugh out loud when they read a particularly amusing paragraph, or forget what time it is as they steal one more minute past midnight to lift the veil on a part of human nature, or stand up and pace in eager excitement after they have experienced an epiphany. I don’t need to be famous and to reach millions through the NYT bestseller list, but I need to at least reach thousands in order to be able to touch one or two significantly.

But how do I get my writing into the hands of these hypothetical readers?

For a long time, I wanted to write books because of all those barriers to entry described above, to fight against this rising tide of over-information. But what's the point of writing a book if no one will buy it? My writing isn't that good yet. My audience isn't big enough, and my followers are not engaged enough yet.

So for a long time, I was stumped by this dilemma, and so I just never published anything. I was always working on my notes—annotating those great authors alluded to above, making connections between disparate genres, developing theories and philosophies and perspectives. My goal was to eventually combine them all into something groundbreaking. I wanted to be like Tarantino—to create works of art that were carved in stone—massive efforts, monolithic, epic, profound, gorgeous, timeless.

But every time I attempted to write a draft, it would eventually lose steam—it wasn’t good enough yet. “I don't know enough.” “This philosophy isn't qualified from enough angles yet.” “The metaphors aren't beautiful enough.” So I was a writer who didn't write. And that is the worst kind of situation to be in. I still wrote in a sense—I was ever diligent about my notes—but I had nothing to show for all that effort.

Breakthrough

Things finally changed for me when my friend Taylor Foreman helped me to realize that I had to become what I hated most in order to become who I truly wanted to be. 7

The solution, ironically, was to throw my own water on top of the ocean of information, constantly putting out essays every week, and tweets (nearly) every day, in the hope that something will resonate, something will stick, will provoke a reaction in people, will get under their skin enough so that they respond, leave a comment, share it with someone, or at the very least click a little heart button. It may not seem like much, but it means the world to me. The more readers interact with this publication (and on Twitter), the more the algorithms promote my stuff, and the more I can touch people. Also, sharing it with others is the most direct and organic path to growth.

The good thing about this process is that I’m finally a writer who writes. In accordance with another nugget of wisdom from Taylor, “I am working on perfecting the writer, rather than the writing.” With each published essay, I get a little bit better. I earnestly believe, to paraphrase Sönke Ahrens, that writing is not what comes after thinking, but the medium in which it takes place. And there’s something even more powerful about publishing to an audience, of whatever size or engagement level: it forces me to truly think better. When I know that someone might read my work, I do a much better job. Call it a corollary to the Observer effect.

The bad thing about this process is that I'm just adding more junk out into the world. I don't really think it's junk, but it's certainly not Hamlet either. But it’s something. I’m earnestly trying to create meaningful content. I don’t want to add mere entertainment, there’s enough of that out there. I want to add something useful, even if it’s only more water, but at least water that’s beautiful and lucid, not murky and ugly.

Sometimes I compare myself to my favorite authors—Thoreau, Wallace, Conrad—and feel completely inadequate.8 But then I remember that I’m not the only one who has felt this way:

“When I write, I feel like an armless, legless man with a crayon in his mouth.” — Kurt Vonnegut

Perhaps I won't be the best. I'm ok with that. I started very late. I have too many other interests. I have spent too much time doing other things—jiu jitsu, video games, guitar, first aid, backpacking, wakeboarding, cooking, etc.—instead of exclusively reading and writing.

Above: me riding instead of writing

“Above them—above almost all of us—are the Shakespeares, the Faulkners, the Yeatses, Shaws, and Eudora Weltys. They are geniuses, divine accidents, gifted in a way which is beyond our ability to understand, let alone attain. Shit, most geniuses aren’t able to understand themselves, and many of them lead miserable lives, realizing (at least on some level) that they are nothing but fortunate freaks, the intellectual version of runway models who just happen to be born with the right cheekbones and with breasts which fit the image of an age.” —Stephen King, On Writing

I may not be one of the best, but that doesn't mean I can't make an impact. It may take years of hard work. I'm ok with that too. It may require me to do the things I least want to—to contribute more to the sea of over-information.

I'm going to have to be ok with not carving in stone, at least not yet. I'm going to have to be comfortable with the equivalent of writing on scrap paper, making mere ephemeral contributions to the literary world. But is that such a bad thing? How does that compare to the rest of our lives? How many of us are able to leave insoluble legacies, stone tablets that stand the test of time?

Vapid

No instead, how much of our lives are actually filled with actions that amount to scrap-paper? Day to day we do the same things over and over. We have our jobs and our tasks and our chores. If we have the time and energy, we exercise. We eat. We sleep. We rinse. We repeat. Even the conversations we have with our coworkers, our clients, our friends, our families, do any of those interactions even matter? In the grand scheme of things, do they leave markings in stone? Probably not. On the one hand, they don't matter at all. It's all ephemeral.

But on the other hand, they are the only things that matter. The little details of each moment—each footstep, each bite, each smile, each conversation—these are the minuscule grains of sand that make up the Great Pyramids of our lives. In the final analysis, they are all our lives consist of.

Sometimes the details of these moments go completely unnoticed, unappreciated. But that doesn't mean they don't matter. Sometimes they affect people in subconscious ways— you might make someone feel simply that "people are smiling at me today."

There’s great truth to the proverb that “people don't remember what you said, they only remember how you made them feel.” That's why everyone knows small talk is stupid and banal and vapid, mere moisture that evaporates immediately, but that's not the point. The point is to connect with other people. To acknowledge their existence. And hopefully, if we can wade through the shallows long enough, we might be able to reach something deep enough to make it all worth it.

Perhaps 99% of those watercooler conversations will never go anywhere, and will never be remembered, but then there are those that leave an unforgettable impression.

Above: handprint from the Chauvet cave, from about 20,000 years ago, which I referenced in this essay

For example, a few weeks ago I had a patient who rode in my ambulance for just 15 minutes, and our conversation may have changed her life.9 She was 14 years old, and had been admitted to a recovery center here in Colorado from her home in Florida. She had an eating disorder, called Anorexia, in which she was unable to eat. This caused her to lose a ton of weight. She was in a really unhealthy state for a while, so her parents finally took her out of school and sent her here. She was in the center for a few months before she had a breakdown and got into an argument with the staff, and, it appears, in retaliation they sent her to the hospital emergency room. There was nothing the ER could do for her, so after checking on her for a couple hours to make sure she was alright, they sent her back to the center. I was responsible for the transport back, making sure she made it safely back there. She probably didn't need an ambulance, but for these types of patients, some of their rights are taken away, and this is how they get moved.

I always try to withhold assumptions when I meet a patient for the first time, but this girl completely surprised all of my expectations. She seemed totally normal. She looked healthy (she had regained some weight after being in the recovery center for a few months now). She seemed rational and level-headed. When I asked her how she got to be in the recovery center, she told me simply that the problem was that she felt too much pressure from her competitive dance program. Her coach had constantly reminded all the girls that they needed to be skinny. My patient found out that not eating was a really great way of doing that, so she just stopped eating. And it worked, amazingly. For a while.

She told me that in the recovery center she has several different professionals that meet with her every week: a dietician, a mental health counselor, a psychiatrist (who can prescribe meds), a life coach, and a clinical director. All of these people have degrees out their asses. What do I have? I have one semester of community college that teaches me how to keep people alive in an emergency. It's mostly very basic human anatomy and biology. I have no formal training in interacting with other people. And yet, by the end of our 15 minute drive, she told me that our conversation was the best one she's had in months.

Though I have no formal training, I know the impact of all those little details in every conversation. What did I do differently than all those professionals who have spent years acquiring specialized knowledge and practical experience in treating people with this particular disorder? I treated her like a human being. Not a specimen, not a medical case study, not an illness. I treated her like she was my sister. Since she is a dancer, I told her about my salsa dancing. She laughed at me. It's ok, I know it's silly. We talked about surfing, and Fall Out Boy, and the woes of high school, and dating, and being a teenager. We just chatted. I also frequently checked her vitals signs during our ride, which is part of my job—but mostly, we just chatted. I listened to her. I paid attention to her. We connected.

An ephemeral interaction for me, but perhaps life-changing for her. For the first time in months, she was treated like what she is—a teenager. She doesn’t need to be treated like an adult just yet. Growing up and going through high school is already brutal enough. She doesn't need the added stressors of an insane dance teacher, unhelpful parents who would send her to another state, over-educated people in lab coats to diagnose her and treat her like she is suffering from a contagious disease, sequestering her in a room away from her friends, away from her cell phone, away from exercise.

Above: a frame from Eighth Grade, which wonderfully captures the agony of growing up, much more so in the age of cell phones

I'm not saying she doesn't have an illness, I'm just saying that perhaps a part of her treatment should involve being treated kindly, being treated with attention, and being listened to. Maybe that's the most important part of her treatment, and something that was severely lacking. Maybe that's the most important thing for all of us—being treated with respect in those ephemeral interactions that happen on a daily basis. And that makes all the difference.

I wrote last week about Gustave Flaubert,10 who felt completely estranged in his hometown of France, unable to relate to any of his peers, an eternal outcast—that is, until he visited Egypt and found his soul's true family. The recognition that there were others in the world like him was a buoy to him throughout the rest of his life. No matter how much of a foreigner he felt among his fellows, he at least knew that there were others in the world who understood him, who saw him and listened to him and acknowledged him. And that makes all the difference.

Conclusion

Maybe I'll get to write a book one day that stands the test of time, something like a stone tablet that lasts for generations. Maybe I'll be as successful as Tarantino and be able to casually walk away from success on a whim because I've already had my fill. Or maybe I'll always be just a small time essayist. Maybe I'll even die tomorrow in a motorcycle accident.

I'd like to leave monolithic works of art that are celebrated for centuries, but maybe the only positive contribution I’ll ever be able to make in this world was that one time I listened to a teenager.

What will you do?

Footnotes:

My good friend Farrar Pace is a perfect example. A graduate of the most prestigious film school in the world, USC, he works his ass off trying to get any gig he can in the industry, even if that means being a PA—which basically means getting coffee. Farrar is talented, hard working, personable. Even with everything going for him, it will take him years of striving in order to break into the directing world, but he is willing to do whatever it takes because he loves it. Check out his vimeo.

I’m indebted to Nerdwriter1 for pointing out this phenomenon in his video essay.

Although I would love to hire an editor soon, and would gladly entertain any offers for a contributing writer.

In addition to the well-known Rosetta Stone, there are actually several other stone tablets that have served a similar purpose.

Also, I’m reminded of the scene in Death’s End where the scientists struggle to find some way of leaving a message on Earth that will last hundreds of thousands of years. What do they do? They don’t leave anything digital (the hardware would corrode), nothing on paper, nothing on metal. They carve a message in stone.

That line kinda sounds like The Dark Knight, don’t it? Here’s Taylor Foreman’s Substack

I wrote about my favorite author in my very first post here.

The details of this story have been changed, but it’s based on something that actually happened to me

Last week’s essay that discusses Flaubert.

I love your story of attunement. We all appreciate how it feels when someone attunes to us and no doubt that 14 year old was blessed by you giving her that gift. Thanks for this thought provoking essay.

I constantly struggle with perfectionism, frozen with choice because I am fearful to make a mistake. To combat this, I create art, where it unfortunately also manifests. Why should I create if it is not perfect? Which then turns, why should I exist if I am not perfect? This is an impossible standard to live by. It is unrealistic and unachievable. So, I try to live by "good enough is good enough" and create anyway. I push past my mistakes and accept my pieces for what they are, physical representations of progress. I continue to have conversations with missteps, even though it's probably easier (better?) if I avoided all human interaction. I try to remember that at least I created, at least I existed, at least I lived, instead of succumbing to my fears of imperfection and not doing anything at all.