Pure Play

It's not just for kids

Three times a week I paid people to beat the shit out of me.

Reminder that scene in Fight Club, where Tyler Durden asks the Narrator to punch him? It was kinda like that.

I joined a fight club.

Although, I'll be honest, I exaggerate a bit. It was not nearly as gruesome or dirty as the one in the movie. Instead, we wore clean white robes and walked around barefoot on spotless cushy mats. We bowed to each other, and the only blood spilled was from accidental nosebleeds or reopened scabs.

Still though, when I started training Brazilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ), I got absolutely thrashed. I paid hundreds of dollars every month to go to those three classes a week, and each class was an hour full of beatings. My classmates twisted my arms and legs and neck to the point where I couldn't take it any more, and I had to tap out. That’s the point of the sport, but it still hurts.

One very memorable time, a guy in my class submitted me 12 times in five minutes. He told me later that he had already worked out earlier that day, and he “just wanted to get a little extra cardio” while drilling with me. I was basically his dummy, and it was embarrassing. And that was not an isolated incident, merely a representative one. In the beginning, BJJ was just a world of hurt, for me.

And yet, I loved it. Not all the pain and the soreness, not the constant humility I felt as I got put into my place over and over—those parts sucked—but I loved the subtle sensation that I was somehow getting better. And I could envision a time, perhaps not too far into the future, when I would finally be the guy smashing rather than getting smashed.

"Sometimes you're the hammer, and sometimes you're the nail."

But it would take a long time to get there, and I wasn’t sure I really wanted to stick with it. At first, everything about BJJ was disorienting. I didn't know how to tie my belt. I didn't know where to stand, or how to count to ten in Portuguese, or how to do the warmup drills. All the terms were foreign to me: armbar, kimora, americana, ankle lock, even one called simply “rear naked.” It turned out to be not as vulgar as it sounded, but it was still definitely savage.

This went on for roughly six months. And then, one day, I got my first submission. It was electrifying. It was like God struck me with a lightning bolt. Of course, I played it cool, as if it was no big deal, but inside, I was thrilled. I wanted to shout and run around the room and strut like I was Connor McGregor. Instead, I just shook my opponent’s hand and we started wrestling again.

In the weeks leading up to that pivotal moment, there had been hints of a submissions, and that was enough to keep me going. Although I was still overwhelmed by the weekly classes, some of the terms were starting to stick. A residue of knowledge began to accumulate, in my head and in my body. I could feel that it was only a matter of time. No matter how broken and sore I was each week, I hung on to that feeling… And eventually, it paid off.

It’s been five years since that day and I'm still loving the sport. It's one of my favorite things in life. Of course, I still get thrashed—constantly—but that's part of the fun, because I get to learn something each time. My skills are forever being sharpened by my friends I wrestle with at the gym, the competitors I meet at tournaments, and the instructors I study from, both online and in person.

And BJJ motivates me in so many other areas of my life. I used to lift weights so I could look pretty. Now I lift weights so I can be stronger; I run so I can have more endurance; I practice yoga so I can be more flexible; I eat well and sleep well because I know that these are the foundation for my success in all these endeavors.

Through this sport, I’ve found a haven of happiness and health, but to get there I have to continually commute through the tunnel of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, which is full of frustrations and difficulties and pain and suffering. For most people, this is about the last thing they would want to do.

But for me, BJJ is pure Play.

If not BJJ, then what is Play for you?

Innate

To answer that question, we have to ask another—what do we mean when we say Play? You may not have given it serious thought before, and I think that's a huge missed opportunity, because Play is one of the most productive and satisfying forces in the world. But too often, we think of Play as something that only kids do.

So let's start there—what does Play look like among kids? All kids Play, no matter what toys they have. I've seen kids in the US play with state-of-the-art drones, and I've seen kids in sub-Saharan Africa kick a ball of trash around to simulate soccer. It's all the same. Give them space and time, and kids will Play. They will chase each other in “Tag!”, they will look out the window and say "I Spy," they will dance and spin in circles until they are dizzy, they will pretend to be soldiers or princesses or lions or unicorns, they will tell jokes and make up nicknames for each other. Play is so ubiquitous among children that it appears to be an innate behavior: even babies play beekaboo.

But it’s not just a human thing, it seems to be a mammal thing too. Have you ever been to a dog park? Dogs chase each other, pretend to scratch each other, bark, yelp and howl at each other. (They sniff each other a lot too, but let's conveniently ignore that). Dogs at a dog park just spend the entire time horsing around—and there goes another example. Horses play too. All they do is just monkey around,,, but you get the point.

Despite the universality of this activity, we seem to Play less as we get older. Why is this so? Perhaps because our responsibilities have proliferated in adulthood. As children, most of our needs are take care of by our guardians: parents, older siblings, schoolteachers, etc. We don't have to worry about buying groceries, or paying rent, or driving to work. But now, all those obligations fall squarely upon our own shoulders. Who has the time to Play when we have all these other things to get done? Especially so in American culture, which places so much emphasis on productivity and busyness.

"You don't stop playing because you get old, you get old because you stop playing."

But we DO play as adults, although in severely limited ways, and therefore we fail to reap the life-giving benefits that it naturally provides. And this is because our understanding of Play is so narrowly-defined. It’s not just something that kids and dogs do, even though that’s the most obvious way to see it in action. So, once again, what is Play?

Play defined

At its broadest level, Play is "free movement within a rigid structure."

Consider two gears that turn in unison. At the start there is a rigid relationship between the two gears.

But over time, the gears start to wear down from the constant friction, so there is a little bit of "play," i.e. there is some wobbling. The system is no longer perfectly efficient, but as an added benefit, it appears to be dancing. And this “play” begins to alter the feeling of the entire system (which is whatever the gears are connected to). With enough time, that "play" can become so great that it eventually causes a fundamental shift in the system itself. And that point will become important later.

Although humans aren't as simple as gears, the analogy holds. Consider a dance. A dance, properly regarded, must follow the rigid conventions of beat and style. If you dance off-beat, you are ruining the whole ceremony, dispelling the enchantment, and embarrassing yourself and your partner. Likewise, if you dance the polka to a country song, or start doing the disco-point-to-the-celling thing during a rap song, you are ruining everything once gain. No, a dance requires you to the follow the strict conventions of beat and style.

HOWEVER, once you are aligned with those two rules, you are pretty much free to do whatever the hell you want. The possibilities for “play” are nearly endless. This phenomenon is the same "free movement within a rigid structure." For example, as I've written before, Salsa dancing, for all its romantic beauty and complexity, is essentially composed of only four moves. And just like DNA is made of only four chemicals, the combinations are nevertheless limitless.

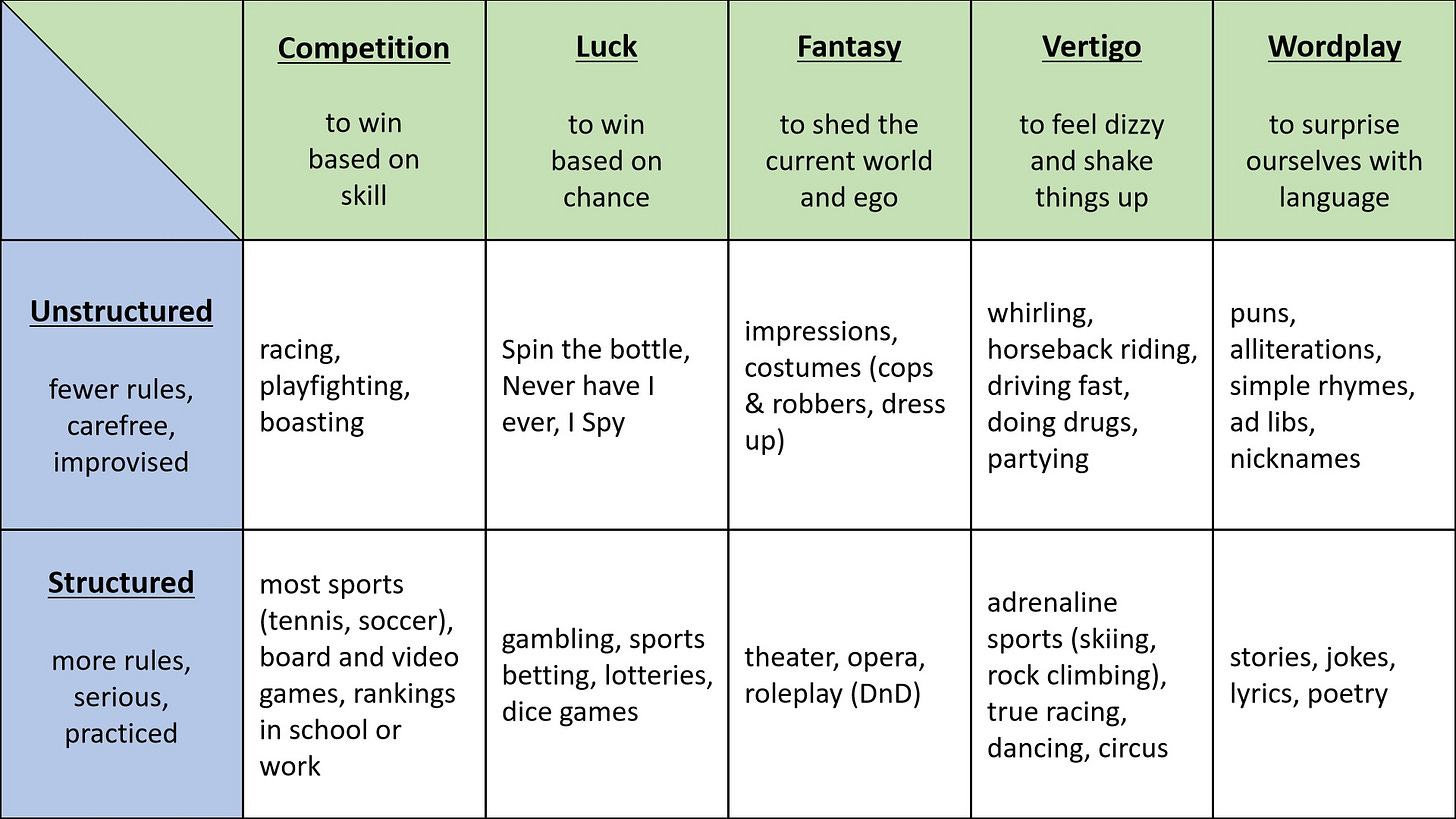

Now that we understand Play in its broadest sense, it's important to break it down into more specific categories, because doing so will help us see its infinite varieties, all of which are still available to us as adults. The following rubric is based on Roger Callois' theory, but I've modified it slightly for my own purposes:

Note that these categories are not exhaustive, nor are the examples within each, and also note that many activities blend different categories. For example, poker requires both luck and skill. Likewise, role-playing games involve both competition and fantasy. And many theater plays (e.g. Shakespeare) involve both fantasy and wordplay. Some activities even blend three or more categories! For example, the moment I wrote about last week, when I was driving a jeep across a self-destructing planet to save the world, combined elements of competition, luck, fantasy, and vertigo.

The problem of seeming to play less as we grow older is actually due to a failure to recognize the vast amount of opportunities that are available to us. As adults, we restrict our Play to a few safe catogories. We avoid the embarrassment of Fantasy or the risk of Vertigo, and instead focus on Competition, particularly in our careers. In doing so, we may rely on the ranking systems of our company (sales leaderboards, promotion schedules), or we may merely boast to our friends and social networks about our job titles, what toys our salary enables us to purchase, or what interesting vacations or hobbies we can afford to enjoy.

If we do engage with the other categories of Play, it is often merely in the role of observer, rather than participant or actor. We love to watch sports (both competitive and adrenaline), but we don't Play them ourselves; they’re too “dangerous.” We love to listen to music, wherein beautiful lyrics are composed, but we rarely write our own poems; we’re not “creative” enough. We love to watch TV shows and movies, where the drama is acted out for us by professionals, but we rarely take the chance to construct or act in our own fantastic worlds, characters, and plotlines; that’s too “childish.”

Visionaries

So at this point, you may be wondering, who cares? Maybe you don't want to Play in all those other ways. But we miss something vital when we fail to truly engage with Play, in all its forms.

Last week, I wrote about how video games have given me the greatest gift I've ever received, which is the ability to flex my imagination. Through the fantasy of games, I can now infuse any situation with excitement and mystery, whether I’m in the beautiful wildernesses of Colorado, or the tedious lines at the grocery store.

But there’s an even more powerful benefit to this ability—it allows me to envision my ideal life, and then, to develop solutions to help me get there.

Sometimes, we are so focused on getting things done,1 on accomplishing the tasks directly before us, that we don't take the time to consider if we are even headed in the right direction. It’s like being so busy putting out fires that we forget to turn off the gas that’s fueling them. It's like the story of the explorers who were so busy cutting down bamboo in their way that they forgot to check if they were still on the right track to the treasure.

Through Play, I get to practice the right side of my brain, which is specialized in visualizing and imagining a future which does not exist yet. And then, when I come to a crossroads where it seems that both choices are terrible, I can imagine a third way. I can develop solutions that also did not exist before, and then circumvent whatever obstacle is thwarting my progress.

To return to the example of the gears, at a certain point, enough “play” can produce a catastrophic breakdown in the system, bringing the larger process to a halt, and forcing the engineers to go back to the drawing board to fix the problem. This is how revolutions occur, both in society and in our own lives. We have to start allowing Play to enter into the rigidity of our adult existence in order for change to occur, in order for us to continually evolve and to adapt to the ever-changing problems of our life.

Conclusion

Lastly, Play is just fun. Life is too short to spend all our time on responsibilities—even the productive ones. Play infuses our lives with energy, excitement, vigor, delight. All of these things are necessary to recharge our batteries so we can return to our responsibilities with even more effectiveness.

"Of all animal species, humans are the biggest players of all. We are built to play and built through play. When we play, we are engaged in the purest expression of our humanity, the truest expression of our individuality. Is it any wonder that often the times we feel most alive, those that make up our best memories, are moments of play?" ― Stuart Brown

As I write this essay, I am filled with enthusiasm as I begin to envision all the things that are Play for me, and I get a thrill from just imagining getting to do them. I love to engage in competitive Play with BJJ, and all the other fitness activities that support it. I love to engage in fantasy Play whenever I watch (and analyze) movies and play (and analyze) video games, or when I write fictional stories. I love to engage in vertigo Play when I go wakeboarding or ride my motorcycle. I love to engage in wordplay whenever I write these essays, or write poems. I love all these things so much that I’ve got to stop writing so I can go out and do them!

What kind of Play makes you giddy to go do right now?

Footnotes

“Getting Things Done” is actually an incredibly helpful philosophy of knowledge management. I use it every day.

So I remembered hearing about 'play personalities' on a Headspace meditation a while back. I looked it up - believe it or not, there's a National Institute of Play, and this guy Dr. Stuart Brown has defined eight different play personalities. They are the styles in which we are most comfortable being playful. And they definitely helped to broaden my view of 'play'. Based on this, I think you embody four of them - but which one are you most comfortable being playful in?

The competitor - access the euphoria and creativity of play by participating in a competitive game with specific rules.

The explorer - exploring can be physical (literally going to new places), emotional (searching for a new feeling or a deepening of the familiar through music, movement), or mental (researching a new subject or seeking out new points of view).

The kinesthete - like to move and naturally want to push their bodies and feel the result (dancing, walking, etc).

The storyteller - for the storyteller, imagination is the key to the joys of play (which you've honed through video games per your prior essay). They may find their greatest joy in reading the novels and watching the movies created by others.

Love this essay...reading it as I prepare for a tennis match this morning!!!