It's 2004. My dad and I are in Caesar's Palace in downtown Las Vegas. It is the final round of the World Series of Poker, the biggest poker tournament ever. It's so popular that ESPN purchased the broadcasting rights last year, and as a result the event has exploded in viewership, with millions watching from home today, including my friends from school.

Fifteen million dollars (!) lie piled up on the table in the center of the casino. Not in cash, but symbolically represented by clay chips of intricate candylike colors. To my mind, they look like they would taste good, if a player bit into them. I am standing as close to the barriers as I can get, looking across the table at my favorite player, "Fossilman" Greg Raymer, whose distinctive raptor sunglasses ostensibly serve to make his poker face even more impenetrable, but mostly they just make him iconic and instantly recognizable.

There are nine players seated at the table, and the tenth is the dealer. Only three of them still have a shot at winning, in my opinion. They are the last men standing, out of over 2,500 others who each arrived here a few days ago with ten thousand dollars in their pockets, or maybe in a briefcase handcuffed to their wrist, or something. I don't really understand the logistics of all that, being 12 years old.

What I do understand is that Greg Raymer's sunglasses are really cool. Also, I understand that part of his allure is that he is **not** a professional poker player; he just got invited here by winning so much online poker. This gives me hope that I could also be invited to the World Series, and win a cool $15 mil. Oftentimes during the tournament, especially during boring moments, I daydream about what I would do with the money. First, I would buy a ton of video games and all the candy and taco bell I could want. If I had some money left over, I would also buy my parents a new home. I'd be the coolest kid in school, and all the girls would like me. If only I could just outsmart everyone else, somehow, then I'd be rich.

We've been standing and watching this final round for a couple of hours. There are hundreds of us in the room, and cameras surrounding the table from every angle, so that everyone at home can see everything we see, and more. I have to go pee.

But this might be the last hand of the night. I can see that Greg is getting frustrated, as he has been losing a lot lately. He has to do something to get out of this slump, or else he will be pushed into the poor players at the table who don't have enough money to push others around anymore.

Things are getting tense. The playful banter between the players has stopped. Everyone is focused on the game. Only Dan Harrington is still chatty. He's the current leader at the table, and the winner of the 1995 World Series, and he's sitting directly before me, but turned the other direction. I can just see over his shoulder and still see my boy Fossilman.

The dealer deals. Greg looks concerned, his brow furrows, as if he's calculating something. We wait. Then, he makes a big bet, pushing a stack of chips into the center of the table. Bold move. We haven't even seen the Flop yet. He must be getting desperate. A minute passes in silence. I shift from one foot to the other.

Finally, Dan responds. He pushes a similar stack into the center. Then another. Then another. He has just bet millions of dollars, about the amount that Greg has left. He's trying to push him out, here and now. Kick em while he's down. Greg has already bet very big on this hand; it's almost too late to back out now. My palms are sweaty. What's he going to do? Greg could get knocked out here, or he could take the leading position. I really don't want Greg to lose. I'd do anything I can to help him win.

As I'm staring at Fossilman, Dan checks his hand one more time. From my position, I can look over his shoulder and see his cards. I know exactly what he has. My heart is racing. I know what he has. I could tell Greg...

Then I do it. I sort of wave my hand at Greg, furtively, and his head turns slightly towards me. Is he looking at me? I don't know. I can't see his eyes. I assume he is looking at me.

Slowly, soundlessly, I mouth to him, "Two of Clubs, Two of Hearts."

He nods, nearly imperceptibly. I think he saw it. If so, he understands that Dan is bluffing him, trying to bully him into submission. Greg calls the bet and goes "all-in," pushing all of his chips into the center of the table. This is it. Do or die.

A few minutes later, Dan reveals his hand, and everyone realizes that Greg has won. Not just this hand, but probably the whole night. Immediately, the crowd erupts into a chorus of cheers and cries and whoops and hollers. Everybody is ecstatic. A lady next to me is crying. I'm jumping up and down. This is what we came to Las Vegas to see: an upset, an underdog victory, a well-played game, and a promise. A promise that anyone could win millions, even people like us. And not just those of us here in Vegas, but the millions watching at home.

And then it hits me... people watching from home... the cameras. Oh crud.

Ten minutes later I'm escorted out of the building by police officers, my hands cuffed behind my back, my Dad yelling for them to stop. They're taking me to jail for helping Greg cheat and win the World Series.

"You're going away for a long time punk," says the huge cop with a handlebar mustache.

"How long?"

"Until you can pay back the $15 million you just stole from the tournament."

I start crying.

Rules

That didn't actually happen. Well, Greg Raymer did win the 2004 World Series of Poker, but he didn't cheat. It was, in fact, the biggest poker tournament ever (at that time), and it was televised on EPSN. But it wasn't in Caesar's Palace. It was actually in some small casino called Binion's Horseshoe, but that didn't sound as compelling. Also, I wasn't there, but that didn't sound as compelling either.

As a writer, I'm allowed to bend the truth a little bit. I can even tell outright lies, as long as they are interesting, and as long as I'm not pretending to that it's a true history. It's called fiction. It's all part of the game, and I'm not breaking any rules.

But when I was accountant, I was definitely NOT allowed to bend the truth. Not even a little bit. The integrity of my work was at stake, not to mention a lot of money.

Nor are Poker players allowed to bend the truth, for similar reasons: the integrity of the game is at stake, not to mention a lot of money. You don't have to always tell the full truth, but you definitely can't cheat. What would Poker be if you could use audience to help you read the other players' cards? It wouldn't really be Poker at all.

No, there are Rules in Poker. The Rules make the game what it is.

Some of those Rules are explicit-- e.g. that you have to go in clockwise order, that a triplet of cards is better than a pair of cards, etc. Some of those Rules are implicit-- e.g. that you should take a reasonable amount of time to make your bet, that you shouldn't peak at another player's hand, etc. Both of these kinds of Rules are important.

It would be a lot easier to win Poker if you could break those Rules. But it would also ruin the game. In fact, in every game, whether tennis or tic-tac-toe or, if you break the Rules, you break the game. They go hand in hand.

"Every game has its rules...But we may go further, and say, 'Every game is its rules,' for they are what define it."—David Parlett, The Oxford History of Board Games

Handicaps

Here's the fascinating part about all this: Rules are restrictions that we voluntary place upon ourselves. Yet, in every other aspect of life, we seek liberation from restrictions. We fight against the tyranny of despots who try to curtail basic human rights. We support freedom of expression, encouraging people to say what they think, with their words, their art, and their life choices, even when we don't agree with them. When obstacles and limitations appear in our personal lives-- financial stresses, relational barriers, physical ailments-- we try to eliminate them. We always want more choices and more options, not less.

However when we play a game, we knowingly and willingly agree to accept restrictions. It's like going to work and asking your boss to tie your hands behind your back. It's like hopping in the car with your kids and asking them to blindfold you. Ridiculous. And yet, we do the exact opposite in games. The Rules of games are voluntary handicaps.

The most obvious example is the game "Three-Legged Race," in which you and your partner each tie one of your legs together, and then you run. It's silly, it's awkward, it's inefficient. But that's the whole point. It's supposed to be difficult. If you and your partner slipped out of the knot and both ran as fast as you could, you would win the race, easily. But it would be a hollow victory. It would mean nothing, because you broke the Rules.

It's the same thing in Poker. If I helped Greg Raymer cheat to win the World Series, would he really be the best? Would he deserve that prize money? Would anyone play with him again?

And this makes it very clear that the point of a game is not just winning at any cost. It's bigger than that. It's about winning within the confines of the game. It's not about winning despite the handicaps, but about winning through them.

So why do we handicap ourselves in games, and not in most other areas of life?

The Magic Circle

Something really weird happens when we play games. Once we decide to play, we cross an invisible boundary and are transported to an entirely different world. This threshold is called "The Magic Circle."

When we play tennis, we aren't just hitting a yellow ball back and forth, we are actually simulating a war. The white lines of the court are the borders of our own personal countries. The ball is a bomb, and if it lands in our country, then we suffer casualties. Everything outside of the lines is water, and we are safe if the bomb goes out there and sinks. The net is a mountain range that divides our two countries, and the bomb will explode harmlessly if it hits that. And so on.

The fantasy world of tennis is not usually that explicit, but you can tell from the reactions of players (especially at the professional level), that things are serious. Deadly serious. People shriek in anger. They break their rackets. They cry. They pump their fists and roar. Something special is clearly going on here with this yellow fuzzy ball and these white lines. What is it?

The term magic circle is appropriate because there is in fact something genuinely magical that happens when a game begins. A fancy Backgammon set sitting all alone might be a pretty decoration on the coffee table. If this is the function that the game is serving--decoration--it doesn't really matter how the game pieces are arranged, if some of them are out of place, or even missing.

However, once you sit down with a friend to play a game of Backgammon, the arrangement of the pieces suddenly becomes extremely important. The Backgammon board becomes a special space that facilitates the play of the game. The players' attention is intensely focused on the game, which mediates their interaction through play. While the game is in progress, the players do not casually arrange and rearrange the pieces, but move them according to very particular rules. —Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, Rules of Play

When we decide to play a game, we enter into The Magic Circle, and we do two opposite things:

1) We voluntarily handicap ourselves, thus saying, "Hey, this is just a game. It's just for fun. It doesn't matter that much."

2) Thus, we are allowed to take the game very seriously, and give it everything we've got, and as a result we experience emotions that would be impossible in everyday life.

Within the game, we restrict ourselves so that we can let go. Ironic, isn't it? And yet I've written extensively about freedom and limits (this is the 7th essay in the series).1 We've talked about how the inherent limits of language allow for infinite variety, how limits like deadlines and routines allow for the most kind of productivity imaginable. So why do we need the limits of Games? What's different about them?

Winning

Rules are what differentiate games from other kinds of play. Probably the most basic definition of a game is that it is **organized play**, that is to say rule-based. If you don't have rules you have free play, not a game. Why are rules so important to games? Rules impose limits—they force us to take specific paths to reach goals and ensure that all players take the same paths. They put us inside the game world by letting us know what is in and out of bounds. —Marc Prensky, Digital Game-Based Learning

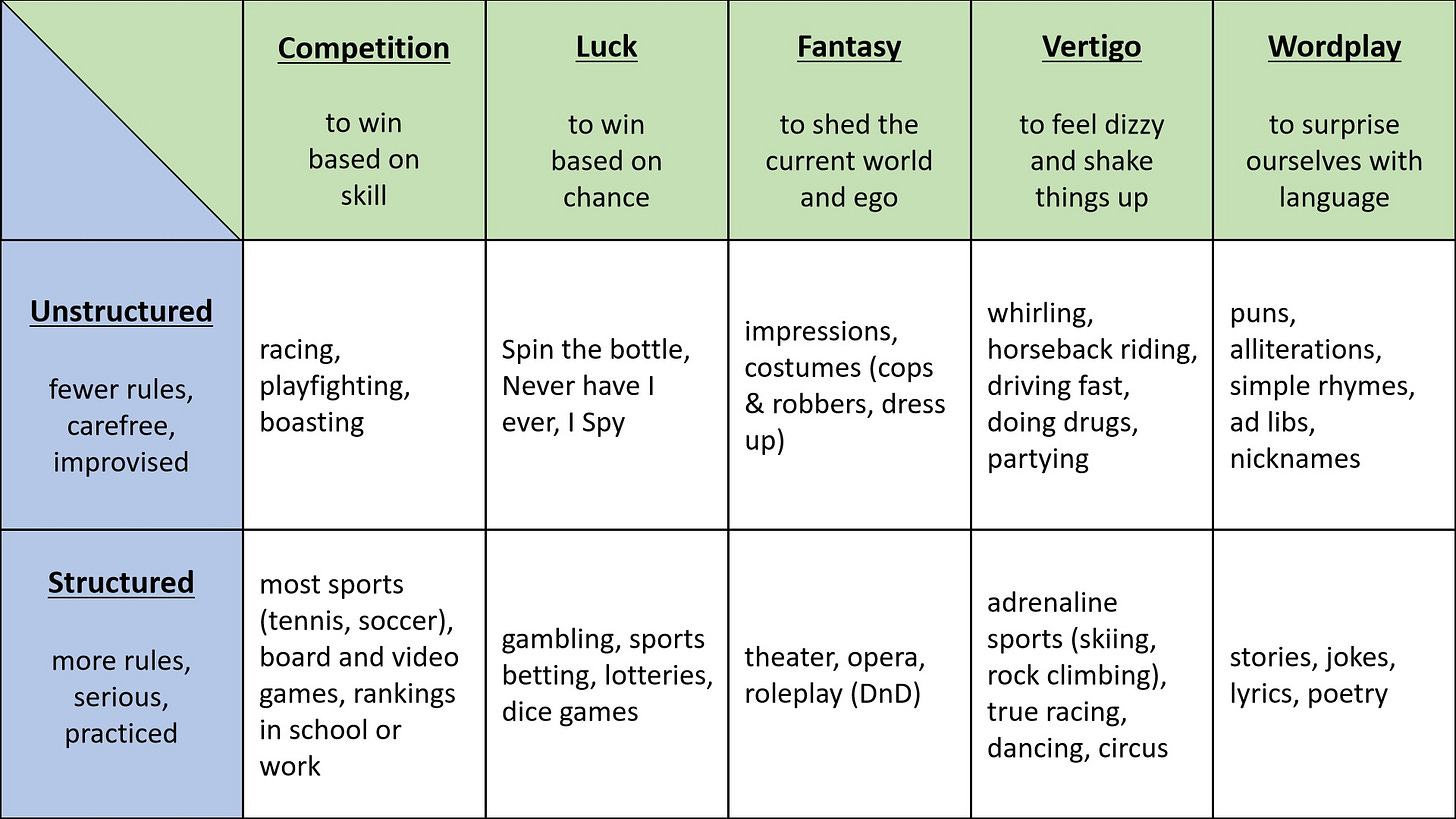

A couple of weeks ago we talked about the concept of Play,2 and broke it down into all its various forms. Some sorts of Play are unstructured, meaning they don't have as many rules. But games are a type of structured Play, which necessitate Rules.

Here's the thing: Unstructured Play is impossible to win.

For example, sometimes kids like to spin around in circles until they feel dizzy and fall down ("dizzy whirling"). Can you win that? No. Maybe you could say that whoever lasts the longest is the winner. But then that's a Rule. The same is true when kids are playfighting, or running around chasing each other. Can you win that? No, not really. It's just about goofing around. The only "Rule" is to have fun and keep the Play going as long as you can. Sometimes this means trying harder, and sometimes this means trying less, but we balance our effort instinctively, automatically.

Contrast those examples with basketball, where we all agree that you can't run and hold the ball at the same time. You can do one or the other, but not both. Think about how weird this is. You can run and dribble the ball, like it's a hot potato, but otherwise you have to pass it or shoot it. Why do we agree to do this? It's a voluntary handicap, which makes basketball the game it is. Otherwise it would be rugby. Or some other sport.

Or what about soccer, where we we all agree that you can't touch the ball with your hands, not at all. Like this time it's a really, really hot potato. Unless, of course, you are standing outside the lines and throwing the ball back in bounds, or you are the one player specifically designated as the goalkeeper AND you are in your little goalie box. What's the point of that? Again, without these Rules, soccer would no longer be soccer.

In contrast to Unstructured Play, then, games are special because you can win them. And that's what makes games different from other forms of voluntary restrictions.

Competition

So what's so important about winning then?

When I was growing up, I played a ton of different sports. I played football, baseball, basketball, and soccer. I was bad at all of them. How did I know? Because we lost a lot, and it was often my fault. The Rules made this very obvious.

So, I kept trying new sports. I tried running, and I was good at that. Then I got bored. So then I tried lacrosse, and I was good at that too. Then I got bored. Eventually, 15 years later, I found Jiu Jitsu, which I love, and which I'm very very good at. How do I know I'm good? Because I win a lot.

But it wasn't always this way. As I've written about before, my first six months of Jiu Jitsu was me getting me ass beat every week. I lost every round. But I got better.

My first tournament, I got knocked out on the second round. Embarrassing. So I tried harder, and got better. The second tournament, I got first place in one division, and second place in another. A big improvement, but not good enough. Back to the drawing board.

Winning is important because it allows us to compete, and thus, to measure ourselves. With unstructured Play, it's impossible to tell if you're doing a good job or not (It's not really the point). But with games, no matter what game it is, you can determine how well you did. There are points and totals and statistics that can now be tracked.

Also, when I was growing up, there was a huge push for de-emphasizing competition. Instead, it was important to make sure that "everybody felt like a winner." So at the end of every tournament, everyone got a trophy, whether you got first place or last place. They called them participation trophies, and they ended up being so empty and worthless that no one gave a shit. In reality, we all knew who was good and who was bad, and we knew that because of the Rules and the scores and the other ways you can measure quality. You can't cover that up.

I knew I was bad at all those other sports, so I kept searching for my "calling." That was good for me. It was frustrating at the time, but without that critical feedback of losing and being bad, I never would have found running and lacrosse and Jiu Jitsu. And even then, once I found them, I never would have improved unless there were Rules to help me to see my weaknesses, and to address them one by one.

We need to know how well we are doing in order to grow. Criticism sucks, but it's necessary. And we won't know what we need to improve unless someone else beats us, in a more or less objective way. Sometimes people will tell you to your face what you are doing wrong, but that’s rare, and even then you can hide behind justifications and excuses. But the Rules of a game are black and white, and let you know the truth.

In real life, it's much more difficult to assess our performance. Things are messy. The Rules of life aren't as obvious. Success is elusive, mostly because it's impossible to universally define. Everyone is seeking different objectives, and those objectives change over time, and our progress towards those objectives is hard to measure. Are you doing a good job at work? Are you doing well in your relationships? Are you staying healthy-- physically, mentally, spiritually? There are some ways to tell, but nowhere is our performance as obvious as in the well-defined arena of games.

Conclusion

In Infinite Jest, there's a character named Eric Clipperton, who wants to be the best high-school tennis player on the continent. He wants to win so badly that he does something insane: he brings a gun to every match, and he points it at his own head, and he tells the other players that if they don't let him win, he will shoot himself. Of course, he only has one hand remaining to play the actual game of tennis, so he's not very good, but this doesn't matter. All the other players let him win.

At the end of the year, he's the best player in the continent, just like he wanted. But did he actually win anything? Technically, he followed all the explicit Rules of the game (the "letter of the law"), but he violated the spirit of the Rules. Yes, he won every game he ever played, and he's the best, but also not really. He will never truly know if he is good at tennis or not. And no one cares.

A win over Clipperton had no meaning because a loss to Clipperton had no meaning... —David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest

The Rules of games, both explicit and implicit, make the games what they are. And more than that, they do something special-- they present us with the Magic Circle, allowing us to enter an entirely different world. In that new world, we voluntarily handicap ourselves, in order to compete, with full abandon, and focus all our efforts on winning. And then, we can see how good we are, and where we are lacking. And then we can improve, and gain confidence, and have fun along the way.

A game is not “just a game.” It’s an opportunity to grow.

And lastly, Life is a game, though the Rules aren't so obvious. Too often, we are so concerned with removing obstacles and restrictions and limitations that we forget that they are there in the first place to enable us to enjoy the game. Or worse still, we try to skirt around the Rules, and find shortcuts, and do things our own way. But that ends up hollow, if it ever ends at all.

Time is limited. So is money. So is energy. So is youth and health and a million other things. There will always never be enough. Instead of trying so hard to get more, play with the amounts you have, and abandon yourself to the pursuit. And make time for yourself to play some other games too.

Enjoy,

Grant

The links to the series on Freedom vs. Limits

Sounds to me like there are some contradictions in here. You can lose and be bad at something at first- but then still excel and be the best. I don’t think losing and being bad necessarily means it’s not your calling. You say you’re glad you were bad/lost at other sports because that led you to lacrosse and jiu jitsu. But you also acknowledged that you weren’t good at jiu jitsu at first either. Because while talent counts, effort counts twice. That’s the argument made by Angela Duckworth in Grit, a book I’ve been reading recently. You can also be good at something, but then not stick with it and not feel its your calling- and ‘get bored’ as you eventually did with running and lacrosse. I don’t think it’s the rules themselves that make someone excel and stick with something, although they can help foster motivation.

In Grit, the author suggests that you won’t go very far in anything without four things:

- Interest – intrinsically enjoying what you do.

- Practice – daily discipline of trying to do things better than we did yesterday.

- Purpose – the conviction that what you do matters.

- Hope – motivates a rising-to-the-occasion kind of perseverance.

So this makes me wonder – you have a strong interest in jiu jitsu; that’s evident. You’ve put in a lot of practice. But do you also feel like doing jiu jitsu has a compelling purpose for you? Like it could really make a difference in terms of your strength? Courage? Discipline? Make you a better person? Part of a bigger community? And do you have faith that you’ll be able to keep progressing? An aspiration to reach that black belt level and hope that you’ll get there? I think that’s what will determine how long you stick with it, how great you become at it.

I ask because reflecting on my own experience with martial arts, I definitely stuck with it so long because it did the above four things for me. I committed to going four days/week (or more importantly, my parents committed to driving me four times a week), it held a higher purpose in that I truly felt my self-confidence growing through learning self-defense and I wanted to get really good so I would never feel threatened when by myself and could travel alone and do things that I might otherwise be afraid to do. I think the different levels (rules in a way) of martial arts are great motivators – especially when there are so many different levels in taekwondo you can advance towards. And it was once I reached black belt that my purpose/hope started to diminish. In that I’d reached my purpose, and I’d conquered all the levels that had been motivating me to excel. So once I got my second degree black belt, it felt like overkill and like I’d learned what I could, had invested enough time (10 years) and I was ready to master a new skill. So in that way, the rules of the sport in terms of progression did motivate me – but it was only one of many other factors that made me excel. Many others quit after their first few months because they’re either not doing it for a higher purpose, don’t have hope that they’ll reach the highest levels, or simply don’t want to put in the practice.

So I think looking at play/games from a rules perspective offers some interesting insights, but that the reasons for why we grow/win or not are much more intrinsic. I think this applies to life too. We know we’re doing well in life when we feel a deep sense of interest/passion, purpose and hope in whatever it is we’re engaged with. And if we don’t feel that, then we’re probably not engaging with the right things and need to keep searching.

Another interesting practice I took away from Grit was this one. She suggests the following process for making the most of the time that is given to us:

1. Write down a list of 25 goals you have (including all the projects you’re currently working on)

2. Do some soul-searching and circle the five highest priority goals

3. Take a hard look at the 20 goals you didn’t circle. These you avoid because they’re what distract you and eat away at your time and energy, taking away from the goals that matter.

4. Ask yourself, to what extent do these goals serve a common purpose? Identifying that common purpose can help identify your true passion.

Shall we do this exercise and then discuss? :)