Solace through solitude

How to be alone with yourself

For a long time, my ultimate fantasy was to be shipwrecked on an uninhabited island.

Remember Cast Away? Tom Hanks survives an airplane crash in the south pacific, and everyone thinks he is dead, so he has to live on his own for like five years, until he builds a raft and sails back to civilization. That's awesome.

Or, even better, remember Robinson Crusoe? The titular character is shipwrecked in the Caribbean, and has to build everything from scratch—hammer, chairs, pots, pen and ink—with "infinite labor"?1 He survives closer to 30 years before escaping. Also awesome.

But my favorite story of a forsaken man, a tale which has fascinated me for years, a mental movie forever seared into my memory, is that of Desmond Hume from Lost.

The story goes like this: one day an airliner crashes on a mysterious island somewhere between Australia and California. Most of the travelers survive, oddly, but that's just the beginning of the strangeness. Weeks go by without any sign of a rescue attempt. Then the group starts to hear a grotesque sound that roams through the forest, plucking up trees like they are blades of grass. And then people suddenly start disappearing in the dark of night. Just when things couldn't get any weirder, they find a metal hatch in the middle of the forest, half-buried underneath the dirt and roots. Completely out of place. No sign of life on the rest of the island.2 Inexplicable. What the hell? Is there someone here?!

They spend days trying to open the hatch, before finally settling on a desperate plan to use some dynamite from a centuries-old pirate ship that (also inexplicably) seems to have just crashed there recently. The first season of the show comes to a close as dynamite explodes and the characters, now nearly rabid with curiosity, wait for the smoke to clear.

In those days, TV shows dropped their episodes week by week, and the suspense that we felt as audiences was enough to make us also go insane. But after a few months of hiatus, season two begins with a bang:

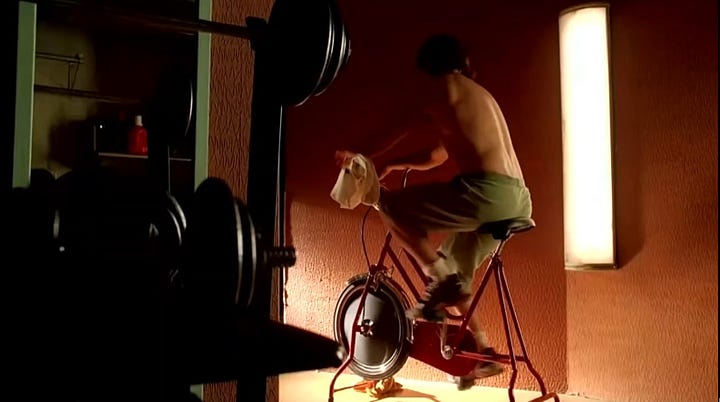

We see a man. He lives in some scientific or government facility,3 and he appears to be completely alone. We get the sense that he spends every day in a rigid routine of wake-up, exercise, listen to music, work on the computer. Rinse and repeat. Day after day, in an apparently endless stream of utter isolation. At least until some big boom breaks down his door…

The rest of the show is memorable and noteworthy in many ways, but in the 20 years since, I’ve forgotten most of the numerous twists and turns, plot points, character arcs, etc. —however—I will never forget that opening segment (lasting only about three minutes). It gave me an unforgettable glimpse into a fictional life that seemed like paradise to me. A world all my own; no distractions, no people to bother me, no obligations to perform, no work to do other than precisely what I wanted to do. It was a fantasy that gripped me for a very, very long time.

And I could go on to explain many more examples of similar stories. Sometimes the hero encounters other people, and sometimes he is the last human left. Sometimes the setting is premodern times, sometimes in the distant future, but they all share the same feature: a protagonist who is completely (or nearly) alone, just surviving (or thriving, as it seemed to me). There is Walden, The Revenant, I Am Legend, The Survivalist, The Book of Eli, The Martian, Fallout, Moon…4

Solitaire vs. Solitary

But I'm not a misanthrope. I often enjoy a good dose of society and fraternity. I actually thrive at social events: happy hours, weddings, house parties, concerts, barbecues, sporting events. If there are strangers around, you will find me breaking the ice. If there is good music playing, you will find me cutting a rug.

So when I tell people about my fantasy, they invariably respond, "Wouldn't you be lonely?!"

But there is a crucial difference between being alone and being lonely. You can be around other people and be completely lonely. And you can be by yourself, and be completely content.

“I find it wholesome to be alone the greater part of the time. To be in company, even with the best, is soon wearisome and dissipating. I love to be alone. I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude. We are for the most part more lonely when we go abroad among men than when we stay in our chambers. A man thinking or working is always alone, let him be where he will. Solitude is not measured by the miles of space that intervene between a man and his fellows.” —Henry David Thoreau, Walden

But why does it seem so shocking that someone would want to spend so much of their time alone? It feels bold, even inappropriate, to share my fantasy with you. As if I’m violating some implicit rule of humanity.5

I think it's because, deep down, we actually know that being totally alone is one of the scariest things that can be done. In a recent essay,6 I wrote about why we so often desire to be around other people, in loud and brightly lit environments, such as a busy street on a Friday night. My assertion was that this urge actually stems from our ancestral fear of being in the dark, but Amy argued that it's actually from our fear of being alone. The two aren't mutually exclusive, but I think she's onto something...

On the surface, most people won't buy this claim, because we often do spend time alone, and do so comfortably—at least as long as we can distract ourselves. We can watch TV, or play video games, or scroll social media, or read books, or play solitaire.7

These things are great at entertaining us... for a while. But eventually, we all get tired of these media, no matter how much variety we pursue in attempt to keep ourselves occupied. And then the worst human emotion begins to creep and colonize us like the expansion of a parasitic mold—boredom.8

Do you remember summers when you were a kid? At first, it is a huge relief to have a break from the school work and finally have some uninterrupted time to just chill. But after three months, it starts to grow tedious. Even if we had summer jobs, or played sports, or had some other activity to engage us, eventually, we got antsy, not just because we want to see our friends again, but because we are starting to run out of distractions. Life seemed to be at a standstill.

When we run out of diversions, a terrible thing happens: we have no choice but to face ourselves. For most people, this is unthinkable, if even at some unconscious level. We will do whatever we have to to avoid this necessity.

Let me ask you this—what is the worst punishment that humans inflict on each other? No, it's not slavery, it's not torture, it's not even the death penalty. The worst thing we do to our most heinous and hardened criminals is this: solitary confinement. We put someone alone in a cell, incommunicable save a narrow slit for food to pass through, day by day by day, no human interaction, nothing to do. Sometimes there isn't even enough light to tell whether time is passing. And we sustain the prisoner just enough to just barely keep them alive, if only to prolong the agony.

“Only seventeen months,” replied Dantes. “Oh, you do not know what is seventeen months in prison!—seventeen ages rather, especially to a man who, like me, had arrived at the summit of his ambition—to a man, who, like me, was on the point of marrying a woman he adored, who saw an honorable career opened before him, and who loses all in an instant—who sees his prospects destroyed…Seventeen months’ captivity to a sailor accustomed to the boundless ocean, is a worse punishment than human crime ever merited.” —The Count of Monte Cristo (1844) by Alexandre Dumas

The Count of Monte Cristo is perhaps one of the most famous stories to describe this kind of torture. The hero, Edmond Dantes, expressed the above complaint after a little more than a year in the dungeon by himself, but he ultimately spends nearly 14 years there. At various times, he contemplates suicide as an escape from the hell of his isolation. But miraculously, it doesn’t end there…

The Man in the Looking Glass

David Goggins is one of the most accomplished endurance athletes of all time, but what makes his story even more compelling is what he had to overcome to get there. He has competed in dozens of ultramarathons, placing in the top ranks multiple times. But he started his competitive career at the age of 30, with no formal training. And before, as a young man, he was a complete loser. He was overweight, lazy, unemployable, self-loathing, piteous.

Then he hit rock bottom. At his lowest point, he finally faced himself in the mirror. He told himself who he really was. No more hiding. No more self-justification.9

But most of us don't have the guts to be mercilessly honest with ourselves. Whenever we are criticized by other people, we immediately become defensive. The walls come up. We justify our behavior. We rationalize. We make excuses. But deep down, the inner self knows that it's all bullshit: “You are selfish. You are lazy. You are not that clever, you are not that smart. You are not special.”

But we avoid this voice at all costs. This kind of brutal self-honesty is the reason most of us can't stand to be alone for long, at least without something to distract us. It feels like solitary confinement. It feels like hell.

But the reality is that even though facing ourselves is one of the hardest things any us can ever do, it's also the most important thing. Perhaps the wisest piece of advice from the wisest10 man of all time is simply this: "Know Thyself." Nothing you do will be effective or meaningful or rewarding until you come to know yourself. Until then, you will be someone else's puppet. You will find yourself following their plans instead of your own. It doesn't matter whether you are obeying the desires of your parents, or your culture, or your friends, or your idols. Until you stare yourself down and come to know yourself, you won't be an autonomous individual.

“Consider the person who insists that everything is right in her life. She avoids conflict, and smiles, and does what she is asked to do. She finds a niche and hides in it. She does not question authority or put her own ideas forward, and does not complain when mistreated. She strives for invisibility, like a fish in the centre of a swarming school. But a secret unrest gnaws at her heart. She is still suffering, because life is suffering. She is lonesome and isolated and unfulfilled. But her obedience and self-obliteration eliminate all the meaning from her life. She has become nothing but a slave, a tool for others to exploit. She does not get what she wants, or needs, because doing so would mean speaking her mind. So, there is nothing of value in her existence to counter-balance life’s troubles. And that makes her sick.” —Jordan Peterson, 12 Rules for Life

Taking off the mask is awful, but it's necessary, if we want to be any kind of adults. And it doesn't just happen once: the first time is not the end of self-deception, but the beginning of a lifelong process of fighting the false self.11 And it's a process that cannot be done alone, and yet nevertheless demands that you spend time alone. It's an alternating journey between exploring the world, meeting other people, learning from them, making mistakes, learning from them, and then returning to the mirror to face yourself and see where you are falling short of your fullest potential. Once done, you make resolutions, and the process begins anew.

“No man, for any considerable period, can wear one face to himself and another to the multitude, without finally getting bewildered as to which may be the true.” ―Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter

After his lowest point, David Goggins turned his life around and got in shape. He went on to become a Navy Seal (the only one to ever face three Hell Weeks), as well as an Army Ranger, and he also served in the Air Force; all this in addition to his multiple athletic accolades in later life. You can be sure that he has been through hell and back many, many times. But he would have never reached the heights of his success if he had not first faced himself in the depths of his depression on that pivotal night.

The man in the looking glass

Is looking back at you at last

You can't hide from the truth

Because the truth is all there is—The Truth, Handsome Boy Modeling School12

Identity precedes Intimacy

In the beginning, it is immensely difficult to face ourselves, but it’s not always so bad. Through pain comes enlightenment. Eventually, we get comfortable with being alone. And not long after that, we begin to crave it.

I have never felt lonesome, or in the least oppressed by a sense of solitude, but once, and that was a few weeks after I came to the woods, when, for an hour, I doubted if the near neighborhood of man was not essential to a serene and healthy life. To be alone was something unpleasant. But I was at the same time conscious of a slight insanity in my mood, and seemed to foresee my recovery. —Henry David Thoreau, Walden

To return to the Count of Monte Cristo, as I said before, it miraculously doesn’t end in suicide, or worse, unceasing suffering. After several years, our hero is incredibly fortunate in that he receives the aid of another prisoner, the Abbe Faria, who communicates to him through a hidden passageway and teaches him many things, but most of all, how to make use of his time alone. During his confinement, Dantes learns philosophy, history, and several different languages, among other things. He is able to ponder the mystery of his false imprisonment and discover the responsible parties. He makes plans to escape and of what he will do once he achieves his freedom.

Finally, Dantes breaks out of prison and returns to civilization, a completely new man, unrecognizeable to even his dearest friends. He later goes on to accomplish many things: he becomes fabulously wealthy, destroys his enemies, and finds his long lost love. All these victories are the result of his instruction by his mentor. But still, the most important thing he learned from Abbe Faria and his time in solitary confinement was how to be alone. Despite the amazing adventures that ensue after his liberation, he still craves that seclusion, which brings him immense peace.

This frequently happened. Dantès, cast from solitude into the world, frequently experienced an imperious desire for solitude; and what solitude is more complete, or more poetical, than that of a ship floating in isolation on the sea during the obscurity of the night, in the silence of immensity, and under the eye of Heaven? —The Count of Monte Cristo

I believe the novel is actually a metaphor for our own journey through the phases of life. At first, we are young and free and vigorous and careless; everything seems to be going well. But then, in our adulthood, we are cast into the world and faced with all kinds of difficulties. We are confined in the prison of adult life: the restrictions of our career paths, the burden of responsibilities, of financial pressures, limited time, and aging bodies. Some people languish within their cells forever. But a lucky few are able to use this time to their advantage; they come to know themselves, and then they flee, taking with them incalculable wisdom and fortitude. Then the rest of their life is full of adventure and and love success and wealth (defined in their own terms, of course).

In the 1950s, psychologist Erik Erikson presented his theory of social development, which closely accords with this narrative structure. The first few stages occur during our childhood, as we learn Trust (of our caregivers), then Autonomy (potty training), then Initiative (exploring the world), then Industry (performing well in school and activities), and finally— the most important step— discovering our Identity. This is what we talked about above, when we each strive to “Know Thyself.”

But this step is necessary in order for us to progress to the most enjoyable and satisfying phases of life: Intimacy (relationships) and then Generativity (contributing to the world).

How can you enter a relationship if you don't know what you like? what you are good at? what you fear? How can you tell your partner what you need help with if you don’t know it already?

How can you help others if you don't know what you have to give, and what your limits are? Your might overpromise and underdeliver. Or you might be able to deliver, and always give and give and give, until you burn out, and are no use to anyone, not even yourself.

In both of these situations, as I said before, you will be more influenced by others than by your own free will.

Conclusion

The uninhabited island fantasy used to be my dream, but it is no longer. I was fascinated by it because I thought all my problems were caused by other people, from their obligations, taking away my time. But after moving incessantly for the past decade, untethered from any long-term community, and also trying a few "Walden experiments" on my own, I realized that true isolation, for an extended period of time, is, in fact, rather like solitary confinement.

I stared myself down in the mirror more times than I can count, and I learned a lot about myself by being alone. I still have much to learn, but sometimes I laugh when I look back at myself 20 years ago, 10, 5, even 2. It’s a never-ending process, but it does get better. As a result, I still enjoy my alone time, and frequently crave it, but I no longer fantasize about a world where that is my reality day after day. Now I can be around other people without letting them sway me. Nor am I afraid to be alone, undistracted. I can find solace through solitude.

Once you truly come to "Know Thyself" you realize that your internal values, your strengths and weaknesses, your likes and dislikes, hopes and dreams and fears and nightmares, your time and energy and enthusiasm and other resources—all of these things may be influenced by others, but they are not controlled by them.

But you have to spend time alone and—importantly—undistracted, in order to come to grips with all these truths about yourself. Like exercise, like education, like any other new activity, it starts out painful, but eventually becomes familiar, and finally habitual. And then we can alternate comfortably between the states of togetherness and solitude. We can be alone and not be lonely.

What’s your relationship with alone time?

Footnotes

“However, I made abundance of things, even without tools; and some with no more tools than an adze and a hatchet, which perhaps were never made that way before, and that with infinite labour. For example, if I wanted a board, I had no other way but to cut down a tree, set it on an edge before me, and hew it flat on either side with my axe, till I brought it to be thin as a plank, and then dub it smooth with my adze. It is true, by this method I could make but one board out of a whole tree; but this I had no remedy for but patience, any more than I had for the prodigious deal of time and labour which it took me up to make a plank or board: but my time or labour was little worth, and so it was as well employed one way as another.” — Robinson Crusoe (1719) by Daniel Defoe

I think this is also a reason why I find The Witness by Jonathan Blow so compelling. I want to write about that one day.

I’m reminded of the facility I passed during my nightmarish motorcycle ride a couple of months ago, which I wrote about in the essay linked below. Perhaps that why it felt so eerie at the time— I was reminded (subconsciously) of the one from Lost.

I wrote about Moon in the essay linked in Footnote #9.

I am, in fact, violating probably the fundamental principle of humanity- we are social animals. We cannot survive without each other. On a physical level, we need to share the burden of getting food and protecting ourselves and specializing our labor. But on a mental level, we also rely on conversation. Language is our strongest capability, but what point does language serve if there is no one to communicate with? Q.V. The Empty Plenum

“That’s the way life on earth works, everybody needs everybody else.”

I wrote our desire to be among crowds in this essay:

Here are some tips if you struggle with living on your lonesome:

"To me, at least in retrospect, the really interesting question is why dullness proves to be such a powerful impediment to attention. Why we recoil from the dull. Maybe it’s because dullness is intrinsically painful; maybe that’s where phrases like ‘deadly dull’ or ‘excruciatingly dull’ come from. But there might be more to it. Maybe dullness is associated with psychic pain because something that’s dull or opaque fails to provide enough stimulation to distract people from some other, deeper type of pain that is always there, if only in an ambient low-level way, and which most of us spend nearly all our time and energy trying to distract ourselves from feeling, or at least from feeling directly or with our full attention. Admittedly, the whole thing’s pretty confusing, and hard to talk about abstractly… but surely something must lie behind not just Muzak in dull or tedious places anymore but now also actual TV in waiting rooms, supermarkets’ checkouts, airports’ gates, SUVs’ backseats. Walkmen, iPods, BlackBerries, cell phones that attach to your head. This terror of silence with nothing diverting to do. I can’t think anyone really believes that today’s so-called ‘information society’ is just about information. Everyone knows it’s about something else, way down." —David Foster Wallace, The Pale King

That night, after taking a shower, I wiped the steam away from our corroded bathroom mirror and took a good look. I didn’t like who I saw staring back. I was a low-budget thug with no purpose and no future. I felt so disgusted I wanted to punch that motherfucker in the face and shatter glass. Instead, I lectured him. It was time to get real.

“Look at you,” I said. “Why do you think the Air Force wants your punk ass? You stand for nothing. You are an embarrassment.”

I reached for the shaving cream, smoothed a thin coat over my face, unwrapped a fresh razor and kept talking as I shaved.

“You are one dumb motherfucker. You read like a third grader. You’re a fucking joke! You’ve never tried hard at anything in your life besides basketball, and you have goals? That’s fucking hilarious.”

After shaving peach fuzz from my cheeks and chin, I lathered up my scalp. I was desperate for a change. I wanted to become someone new.

“You don’t see people in the military sagging their pants. You need to stop talking like a wanna-be-gangster. None of this shit is gonna cut it! No more taking the easy way out! It’s time to grow the fuck up!”

Steam billowed all around me. It rippled off my skin and poured from my soul. What started as a spontaneous venting session had become a solo intervention.

“It’s on you,” I said. “Yeah, I know shit is fucked up. I know what you’ve been through. I was there, bitch! Merry fucking Christmas. Nobody is coming to save your ass! Not your mommy, not Wilmoth. Nobody! It’s up to you!”

By the time I was done talking, I was shaved clean. Water pearled on my scalp, streamed from my forehead, and dripped down the bridge of my nose. I looked different, and for the first time, I’d held myself accountable. A new ritual was born, one that stayed with me for years. It would help me get my grades up, whip my sorry ass into shape, and see me through graduation and into the Air Force.

—David Goggins, Can’t Hurt Me

Socrates was also the most annoying man who ever lived, or, at least, I think so.

"Life’s endless battle of the self you can’t live without.” I wrote about the eternal internal struggle in this essay:

The Truth:

I love this essay! For me alone time has to be intentional, scheduled, and I have times when I crave it. I believe if we’re not in a good place emotionally and mentally, we know it and alone time is scary and thus avoided. Without it, however, we never get to that good place.

I thought I was totally okay with being alone for extended amounts of time, but this made me realize that I do actually need company. Thanks for helping me a bit with facing myself.